The year was 164 AD.

The Roman Empire was near the height of its powers. Its borders extended across most of Europe and well into Asia and North Africa.

Marcus Aurelius’s co-emperor, Lucius Verus, was leading an army to the city of Seleucia in what is now Iraq. There had been an uprising against Roman control. He planned to crush all involved.

When his massive force arrived at the gates to Seleucia, the city’s leadership knew they couldn’t withstand the assault of an experienced and well-trained Roman Army. Their losses would be devastating. And so, quite wisely, they surrendered, opened their gates, and hosted the army.

Within days, Verus noticed several soldiers coughing and develop fevers. Some of them worsened and developed sores. A few of them never left the city.¹

As they began their long march home, the disease began to take its toll on other soldiers. There were several stops for extra rest and, eventually, stops to bury the dead.

With tragic irony, the army that had been tasked with defending the Roman Empire would soon be the harbinger of a terrible scourge. As they stopped in local towns to rest, they left an eager contagion to do its work.

The widening impact

After the army reached Rome and dispersed into the city, the virus swept across all of Europe. Entire towns and communities were ravaged. Death toll estimates vary but most agree that around five million died, including at least 10% of the Roman population.²

The virus was particularly devastating to the military. They lived in close quarters. They trained and fought to the point of exhaustion which weakened the immune system. They also had gaps in rations (nutrition) which further predisposed them to the disease.

Those afflicted typically developed a severe fever, diarrhea, and visible sores that spread across their entire body. Soldiers who survived were often hampered by disabilities and weakness. Their bodies were marked by terrible scars and pockmarks which announced they’d survived the infection. Most scholars now agree the disease was smallpox. But it is commonly referred to as the Antonine Plague.

All offensive military campaigns were postponed. Rome’s fighting force was cut in half. Their recruiting pool ran dry as people became wary of the close confines of military service. People didn’t understand virology like we do today, but most knew to avoid those who were visibly sick.

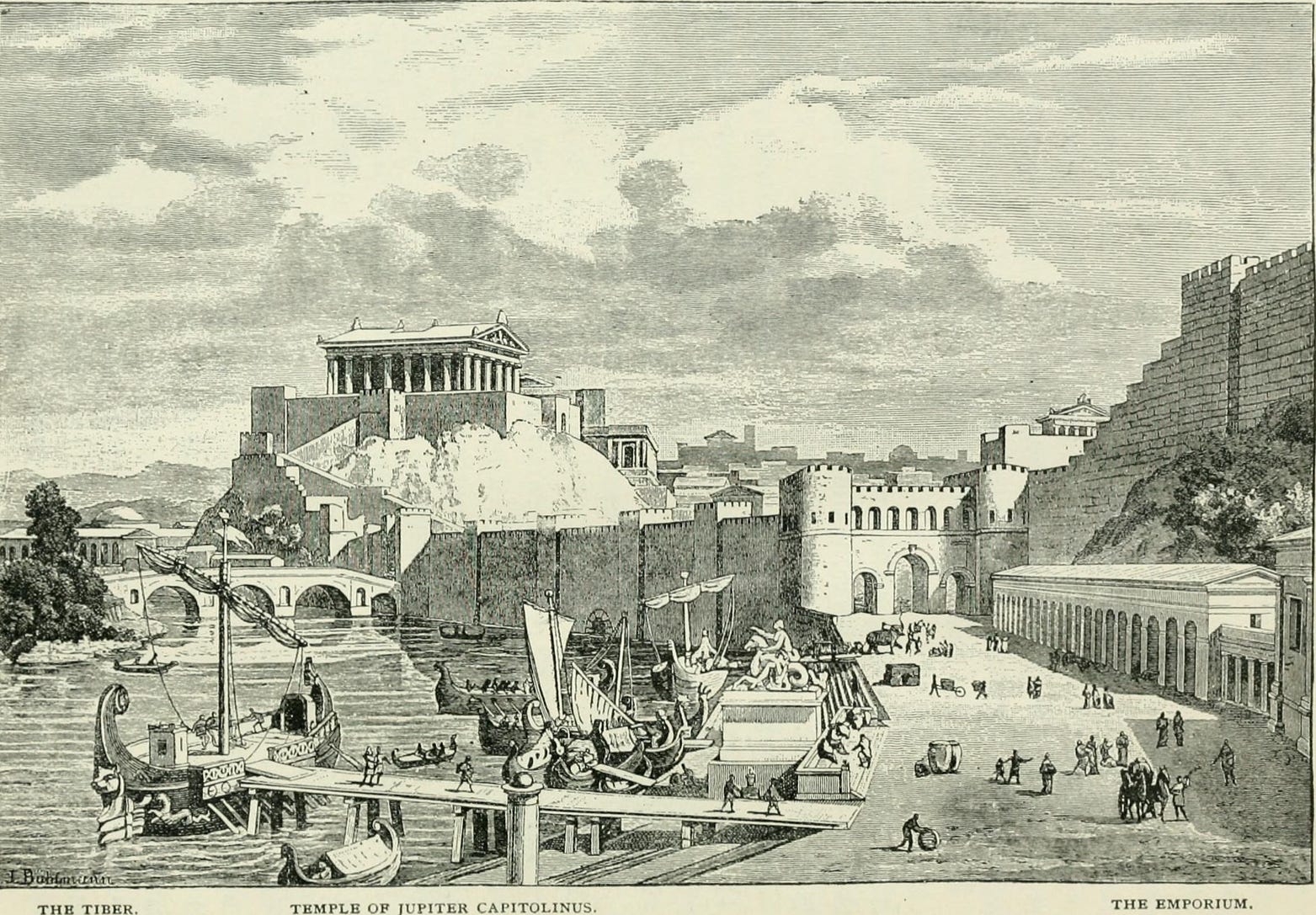

In Rome, the economy was crumbling. People avoided public areas and markets. Many businesses shut down. This trickled into the government's ability to create revenue and send supplies to military outposts.³ Feeding troops became more problematic as the populace began to hoard supplies, grain in particular, which was a chief source of nutrition.

The roman guardposts in the northern and eastern reaches of the empire were eventually hit with the virus. Trade routes for rations became highways for the disease.

Germanic tribes, which had been raiding for years, began to push into Roman territory. Lucius Verus then scraped together an army to reinforce the region and push back the tribes. During their journey, they passed many towns and villages that had been abandoned and gutted by the disease.

They were successful and defensive campaigns like this continued. But as Germanic tribes claimed more territory, Rome began conscripting gladiators into their army, as well as farmers and citizens who wouldn’t ordinarily qualify for military service. This would have permanent ramifications for the trajectory of this empire.

No rest for the wealthy

Germs were the great equalizer of Roman society: money and status couldn’t save one from infection.

Medicine was mostly useless against the virus. Roman doctors had limited treatments and often resorted to herbs, incantations, and prayers to the gods. The solutions used by the world’s leading medical expert, Galen, were outrageous. He’d be immediately stripped of his medical license by today’s standards, if not jailed.

In the ultimate act of indiscriminate virulence, co-emperor and military leader, Lucius Verus, was infected and his health declined over the course of several weeks. He eventually died from the disease.

Marcus Aurelius was left to manage a thinned out and resource strained military, in addition to his other duties.

The trickle effects

Nearly every citizen lost immediate family members to the Antonine Plague. The suffering was terrible. The disease’s symptoms worsened for weeks. Many of the infected would be seen begging for death.

The pandemic left a lasting impression on the emperor. More than a decade after its outbreak, when he was on his death bed (of natural causes), he said, “Weep not for me; think rather of the pestilence and the deaths of so many others.”³

The Antonine Plague laid the groundwork for the unraveling of the Roman Empire. It exposed their dependency on connected trade routes. It lowered their standards for military service, which would both impair their geographical control and decrease esteem for Rome’s leadership.

The continued tradition of undertrained, ill-equipped soldiers, political breakdown, pressing germanic tribes, and a second virus outbreak, would all be major factors in the downfall of the Roman Empire.

But the crushing of its military by this virus was the first shot across the bow.

Sources

[1] McLaughlin, Raoul. (2010) Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the ancient lands of Arabia, India, and China

[2] Verity, Murphy. (2004) Past pandemics that ravaged Europe. BBC News.

[3] McLynn, Frank. (2009) Marcus Aurelius, Warrior, Philosopher, Emperor. Vintage Books.

No comments:

Post a Comment