Foreign Affairs

The Dangers of a Weak Iran

How a Wounded Islamic Republic Can Still Threaten the World

Afshon Ostovar

March 12, 2026

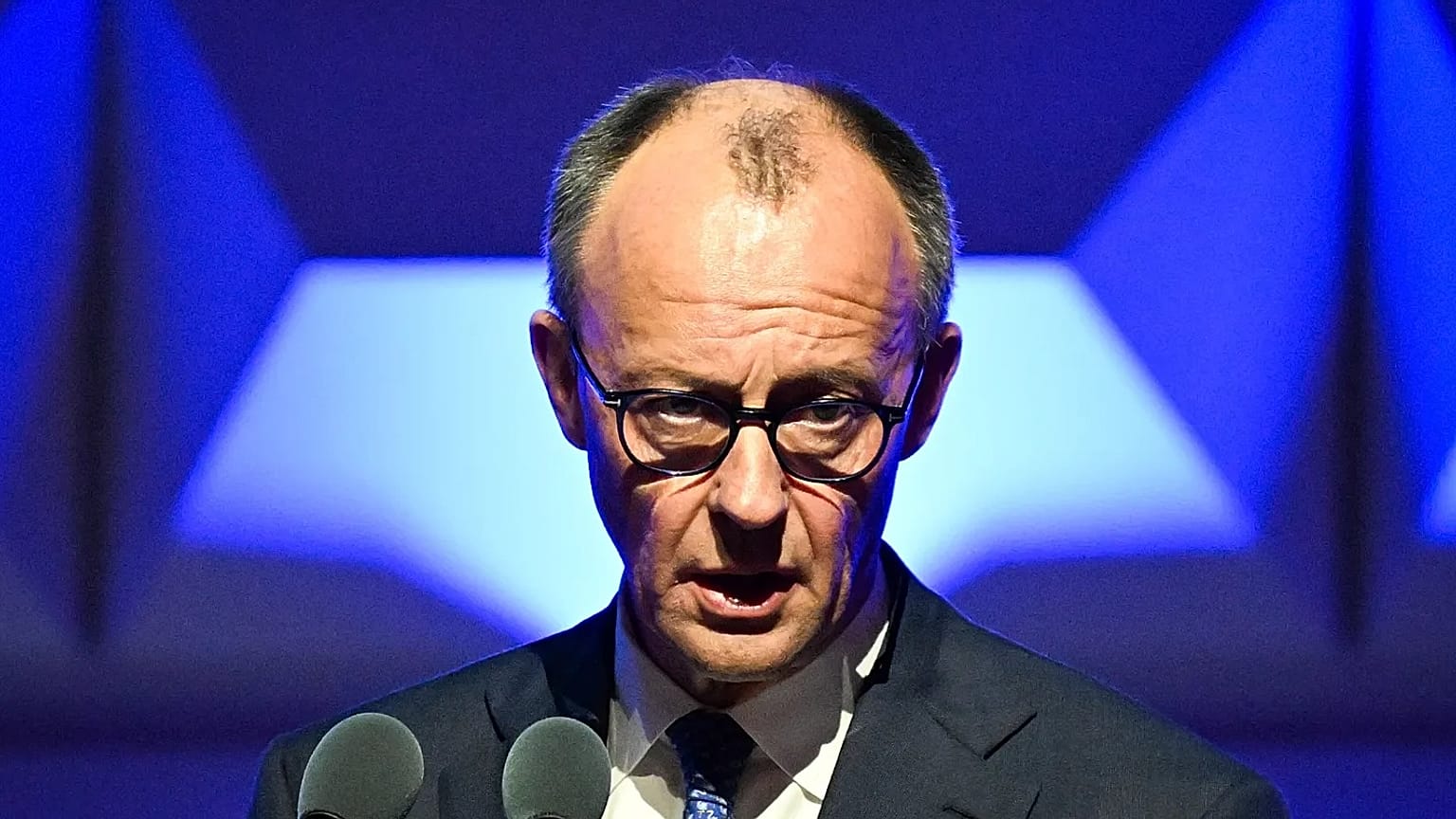

A man holding a picture of Iran’s new supreme leader, Mojtaba Khamenei, Tehran, March 2026

Majid Asgaripour / West Asia News Agency / Reuters

AFSHON OSTOVAR is an Associate Professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and the author of Wars of Ambition: The United States, Iran, and the Struggle for the Middle East.

After nearly two weeks of withering attacks, the Islamic Republic is weaker than it has been at any point in its history. U.S. and Israeli strikes have killed much of its leadership, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, destroyed much of its navy, heavily degraded its missile program, and buried its nuclear facilities. Bombings have cratered government ministries, police stations, and military buildings. Even the headquarters of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—or the IRGC, the country’s most powerful institution—has been reduced to ruins.

But although the Islamic Republic is down, it is not out. The regime selected Khamenei’s hard-liner son, Mojtaba, to succeed him as its leader, opting for continuity in the theocracy’s most important position. Government officials are united behind the retaliatory campaign Iran is now carrying out against the United States and its partners, and the IRGC remains functional. The Islamic Republic is still very capable of inflicting violence on its adversaries, neighbors, and people.

If the regime holds on to power, it will, no doubt, be in an extremely difficult position. The strategic programs it had spent decades developing (such as its missile and nuclear enrichment infrastructure) have been severely weakened. Its relations with its neighbors are in crisis, and its economy is bleeding. But even with a bad hand, officials are likely to stick with what they know: resistance and aggression. Defenseless and with dwindling capabilities, they will probably fall back on old habits and take new risks. That means they could retaliate by carrying out more acts of terrorism, which is a low-cost tool the regime has already mastered. In the long term, Iranian officials may finally dash for and build a nuclear weapon. A weak Iran, in other words, will remain very dangerous.

REAPING AND SOWING

Ever since its 1979 founding, the Islamic Republic has worked to become the Middle East’s predominant power. Its leaders have poured billions of dollars into proxy militias, ballistic missile programs, naval forces, and nuclear facilities in hopes of overturning the region’s United States–centered order and remaking the Middle East into a bastion of Islamist resistance.

To pursue the regime’s ambitions, its leaders created a series of often overlapping institutions—most important, the IRGC. Under the authority of Ali Khamenei, the IRGC was empowered to build Iran’s proxy network, establish the country’s missile and drone forces, and hone its naval capabilities in the Persian Gulf. The IRGC also gained outsize influence over Iran’s foreign policy and internal security. Eventually, the organization came to dominate even Iran’s domestic political scene. It commands the country’s Basij paramilitary force, which is charged with ensuring that Iranians stay loyal to the regime. To do so, the Basij have built bases across Iranian cities and towns, sometimes embedding them in mosques or other religious buildings. Basij members are routinely deployed in times of popular unrest, serving as a frontline force in combating dissent.

For decades, these efforts were broadly successful. The IRGC seized on the chaos created by the Middle East’s wars to cultivate armed groups across the region. It used missiles and drones to coerce its Arab neighbors and to threaten Israel and U.S. forces. Ordinary Iranians did not benefit from these programs; in fact, military spending and sanctions targeting Iran’s nuclear program immiserated the country’s people. Yet the IRGC’s approach transformed the Islamic Republic into a power player that, by 2023, effectively controlled a broad swath of the Middle East—from Lebanon to Iraq.

The Islamic Republic has adopted simple and achievable goal: survival.

The regime’s tenacity and risk-taking, however, proved to be a double-edged sword. The constant aggression may have expanded Iran’s influence, but it sank Iran’s economy and provoked a fight with Israel. The October 7, 2023, attacks on Israel by Hamas, an Iranian client in Gaza, were the inflection point. Israel not only turned its guns on Hamas; it also decimated Iran’s proxies in Lebanon and the IRGC’s positions in Syria. Tehran countered that aggression with massive missile and drone strikes against Israel’s territory in April and October of 2024. But Israel intercepted most of these attacks and used its superior military to knock out Iran’s air defenses. In June, Israel conducted a 12-day war against Iran, culminating in a U.S. bombing operation that destroyed Iran’s most fortified underground nuclear enrichment sites.

In the following months, Tehran repaired as many of these capabilities as it could. With the help of China, the regime got its missile industry back online. Iran also began constructing new sites that could be used for nuclear activities. But these activities sent the wrong message to its adversaries, and by the end of February 2026, U.S. and Israeli forces began an onslaught to finish what they had started: the complete destruction of Iran’s key nuclear and military capabilities.

Because Tehran can’t defend its skies (thanks to the decimation of its air defenses), it has been unable to stop these strikes. As a result, the regime has chosen to draw the entire region into the war in hopes that attacks on Gulf Arab countries and disruptions to the oil industry will pressure Washington to back down. But Tehran will not be able to keep striking its neighbors indefinitely because it has only a fixed number of drones and missiles. And even if its strategy succeeds, the damage will still have debilitated the Islamic Republic.

REIGN OF TERROR

Iran knows that it cannot defeat Israel and the United States militarily. It has thus adopted a simpler and much more achievable goal: survival. Even though U.S. President Donald Trump has called on Iranian citizens to rise up, an air campaign alone cannot get rid of the personnel and small arms that the regime uses to stamp out protests. Meanwhile, the Islamic Republic’s supporters—including civilian officials, security force commanders, foot soldiers, and Basij volunteers—have displayed impressive unity and resilience.

Should the regime outlast the U.S.-led campaign, it will likely declare victory. It will make this declaration on moral grounds, claiming that it had successfully withstood a war conducted by two of the world’s most powerful militaries and aimed at ending the Islamic system. Such claims are what held the regime together during its nearly eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s and allowed it to deem that disastrous conflict, which killed hundreds of thousands of Iranians, a win for the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Following that war, the regime turned to vengeance, aimed both internally and externally. The country’s infrastructure was crumbling, its economy was in tatters, and its people were exhausted, but the IRGC was ascendant, and it used the conflict to legitimize its expanding political power and stamp out a nascent reformist movement. Iran’s leaders were also fueled by thirst for revenge and turned to terrorism to lash out. In 1994, for example, Iranian proxies blew up the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association building in Buenos Aires, killing 85 people.

The regime may follow a similar path if it survives its current war. It will, after all, be embittered, embarrassed, and vengeful—and have little to lose. The regime could thus pursue a series of revenge attacks against Americans, Israelis, Canadians, or Europeans living in third-party countries. Intelligence agencies can generally foil such efforts, but not always; Hezbollah, for example, murdered Israeli tourists at Bulgaria’s Burgas Airport in 2012. If the regime increases the number of attempted terrorist attacks, more of them will succeed. And despite its diminished resources, Iran is likely capable of organizing such attacks. As September 11 showed, terrorists don’t need missiles, drones, or a navy to commit mass murder. They need only the will and a cause.

There is also the risk that Iran will dash for nuclear weapons if it keeps its stockpile of highly enriched uranium. Iranian officials have often spoken of Khamenei’s formal religious ruling that prohibited nuclear weaponization as a reason why Tehran would never create a nuclear weapon. But now that Khamenei is dead, his edict is no longer binding. Instead, it is up to Mojtaba to issue his own judgment. And given Iran’s profound current military weakness, he may well decide that nuclear weapons are necessary to restore deterrence.

MAXIMUM AGGRESSION

A bad outcome for Iran isn’t guaranteed. It is possible that pragmatic elements within the regime will convince their colleagues to strike a deal with Washington in which they abandon decades of aggression and their nuclear ambitions in exchange for sanctions relief. The new supreme leader—whose father, mother, and wife were killed in the war—is unlikely to be amenable to such a compromise. But it would be the best way for him to secure his regime and open the way toward gaining some sort of popular legitimacy. It might even be the wisest personal course for him and other government elites, who are all at risk of being killed by Israeli and U.S. forces. Whenever the war ends and whatever happens next, Iran’s security has been thoroughly broken. The country’s officials will remain exposed.

But prudence has never been one of the Islamic Republic’s traits. Time and again, the theocratic regime has proved that its aim is to advance its narrow ideological agenda, not help the Iranian people. Rather than compromise, it has impoverished the country, killed thousands of its own citizens, and picked fights with far stronger militaries. It is unlikely that the regime will carry out substantive change if it survives this campaign. Instead, the remaining, aggrieved cadre at the helm might lead Iran down an even darker path.