Home Analysis South Korea’s Standoff Over Martial Law

South Korea’s Standoff Over Martial Law

The president’s shock declaration took many by surprise.

South Korea’s president took the extraordinary step on Dec. 3 of declaring martial law. In announcing the move, President Yoon Suk Yeol accused the opposition Democratic Party of “anti-state activities” and efforts to block the operation of government. Within hours, 190 of 300 lawmakers convened and voted unanimously to demand that Yoon revoke the martial law declaration – an order that the president must respect, according to South Korea’s Constitution. A few hours later, Yoon relented on what was bound to be a test to Seoul’s democratic institutions, the regional geopolitical order and the strength of South Korea’s alliances.

South Korean leaders have invoked martial law several times in the nation’s history, typically during turbulent times and often coincident with military coups, but the last time was in 1979. In the latter case, the ensuing pro-democracy backlash eventually led to the country’s complete adoption of democracy in 1987.

The type of martial law invoked by Yoon (emergency rather than security) is intended for times when a major crisis such as a war or rebellion prevents the state from executing its responsibilities. It essentially suspends civilian authority and grants broad powers to the military. Yoon’s order, in addition to dissolving parliament and banning public demonstrations, also required medical interns and residents, most of whom have been on strike since February, to return to work within 48 hours.

South Korea is not at war or facing a rebellion, so Yoon’s order came as a shock. Instead, Yoon apparently meant for the declaration to break the political impasse gripping the South Korean government. Yoon’s administration has been at loggerheads with the parliament, where the opposition Democratic Party holds a majority, over several critical pieces of legislation, most notably the 2025 budget bill. The stalemate has left the government unable to address pressing issues involving the economy and disruptions to public services. Compounding the crisis were Democratic Party efforts to impeach prosecutors who opted in October not to charge Yoon’s wife over allegations of investment fraud and accepting inappropriate gifts. Besides the political gridlock, strikes by junior doctors and other health care workers have impeded the delivery of essential medical services and contributed to the sense of crisis. All this, according to Yoon, amounted to an attempt by “anti-state” forces and North Korea sympathizers to disrupt the constitutional order.

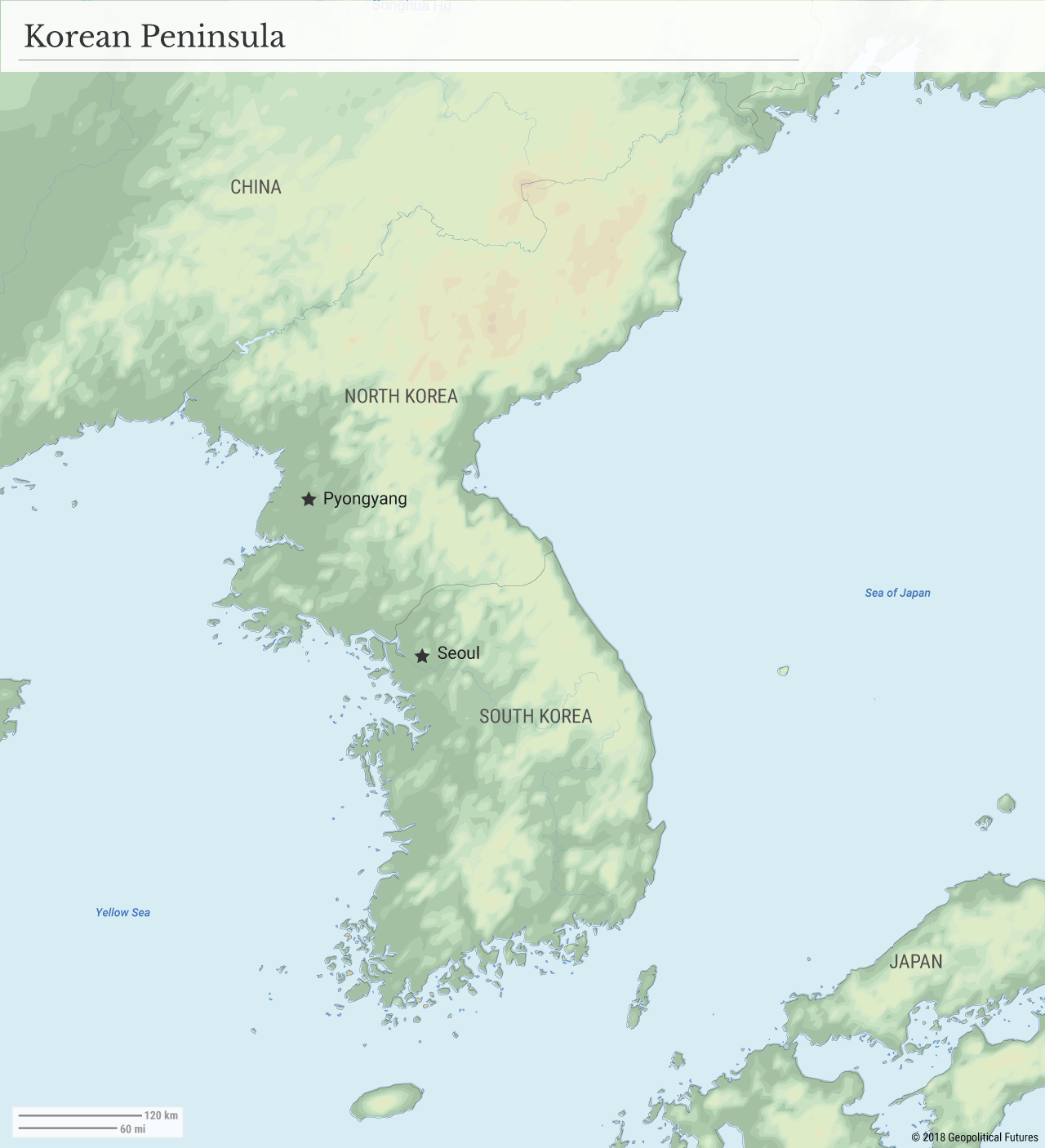

Although the declaration of martial law did not mention it, developments in North Korea also probably influenced the decision. In recent months, Pyongyang has intensified its military activities, including conducting multiple missile tests, and has made repeated threats against Seoul and its allies. By framing its domestic opponents as sympathizers with the communist North Korean regime, the Yoon administration sought to prove that martial law was a necessary measure to safeguard the nation’s security against internal and external threats.

Rather than stabilize the situation, however, the invocation of martial law was liable to trigger more instability. Lawmakers quickly gathered and voted down the declaration. Opposition parties and civil society groups described martial law as a threat to the nation’s democratic freedoms, which were secured only in the late 1980s after decades of authoritarian rule. Moreover, a paralyzed South Korean government would be ill-equipped to defend the nation against North Korean aggression, and it could have encouraged Pyongyang to exploit the situation to its benefit. In a worst-case scenario, it could have resulted in a military confrontation, but even developments short of war could have complicated efforts to manage North Korea’s provocations through diplomacy and upset the balance of power in East Asia. Finally, a prolonged bout of martial law would likely have strained the U.S.-South Korean alliance, a cornerstone of regional stability, as well as South Korea’s relationship with Japan. With approximately 28,500 troops stationed in South Korea, the U.S. has a vested interest in the country’s stability and democratic integrity.

No comments:

Post a Comment