Putin´s Next Steppe: Central Asia and Geopolitics

12 Dec 2016

By Benno Zogg for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy (No. 200) was originally published in December 2016 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

In the five Central Asian republics, the chronic problems that plague the authoritarian regimes in power are meeting a changing geopolitical landscape: Russia after Crimea is ever more prepared to defend its influence, China’s leverage is growing, and attitudes of the West are changing after the partial retreat from Afghanistan. Events like the recent death of Uzbekistan’s president may trigger wider change.

As part of Russia’s hitherto undisputed sphere of influence, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan seem far from the geopolitical hotspots. Yet, due to both internal and external pressures, Central Asia will undergo great changes in the years to come and should be observed closely. The countries’ authoritarian regimes, largely legacies of the Soviet Union, have created stability for their nations through resource rents, networks of corruption and the oppression of opposition groups. The events of September 2016, however, revealed that continued stability is not guaranteed. Uzbek president Islam Karimov, who had led the nation since its independence in 1991, died at the age of 78. News of his death went unconfirmed for a week, which allowed the Uzbek elite to bargain and negotiate over his successor free from public scrutiny. Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev was declared interim president, and won the unfree elections on December 4th.

Despite the apparent smoothness of the transition in Uzbekistan thus far, the whole of Central Asia is unlikely to remain stable over the next few years. The republics suffer from several chronic problems, causing both economic instability and popular discontent: endemic corruption, weak and ineffective economic reforms, and a poor record of democracy and human rights. Moreover, governments seem incapable of solving regional issues on a bilateral or multilateral basis. Border demarcation, access to water, inter-ethnic quarrels, and cross-border terrorism and organized crime continue to cause regional tension.

In the five Central Asian republics, the chronic problems that plague the authoritarian regimes in power are meeting a changing geopolitical landscape: Russia after Crimea is ever more prepared to defend its influence, China’s leverage is growing, and attitudes of the West are changing after the partial retreat from Afghanistan. Events like the recent death of Uzbekistan’s president may trigger wider change.

As part of Russia’s hitherto undisputed sphere of influence, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan seem far from the geopolitical hotspots. Yet, due to both internal and external pressures, Central Asia will undergo great changes in the years to come and should be observed closely. The countries’ authoritarian regimes, largely legacies of the Soviet Union, have created stability for their nations through resource rents, networks of corruption and the oppression of opposition groups. The events of September 2016, however, revealed that continued stability is not guaranteed. Uzbek president Islam Karimov, who had led the nation since its independence in 1991, died at the age of 78. News of his death went unconfirmed for a week, which allowed the Uzbek elite to bargain and negotiate over his successor free from public scrutiny. Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev was declared interim president, and won the unfree elections on December 4th.

Despite the apparent smoothness of the transition in Uzbekistan thus far, the whole of Central Asia is unlikely to remain stable over the next few years. The republics suffer from several chronic problems, causing both economic instability and popular discontent: endemic corruption, weak and ineffective economic reforms, and a poor record of democracy and human rights. Moreover, governments seem incapable of solving regional issues on a bilateral or multilateral basis. Border demarcation, access to water, inter-ethnic quarrels, and cross-border terrorism and organized crime continue to cause regional tension.

President Nursultan Nazarbayev (center), aged 76 and head of state of Kazakhstan since independence in 1991, is surrounded by WW2 veterans at Red Square in Moscow. Reuters

These structural factors in the region interact with broader changes in the geopolitical landscape. Since its invasion of Crimea in 2014, Russia has proved to be the most powerful game changer in the region. If Belarus or Ukraine are considered Russia’s front yard, Central Asia is its back yard. Particularly in the security realm, Russian influence is undisputed. Yet the weak Russian economy leads many to conclude that Russia is in decline, investment levels are dropping, and opportunities for the roughly four million Central Asian migrant workers in Russia are waning. Over the last decade, China has replaced Russia as Central Asia’s largest trading partner. These factors are compounded by the downsizing of NATO’s decade-long presence in Afghanistan in 2014, which altered Western attitudes towards the region.

Given these developments, unforeseen events or major shifts of power within Central Asia could trigger wider change. How would the Kremlin react if the death of Kazakhstan’s 76-year-old President Nursultan Nazarbayev brought to power a government that opposed Russian policy in the area? Would Russia choose to intervene, as it did in Crimea and Donbass? How would major powers react to a wave of terrorist attacks perpetrated by some of the 4000 Central Asian jihadist foreign fighters returning to their homeland, or a breakdown of public order in Tajikistan? Lastly, will Central Asia be the stage of a new “Great Game” between a waning Russia and waxing China?

Given these developments, unforeseen events or major shifts of power within Central Asia could trigger wider change. How would the Kremlin react if the death of Kazakhstan’s 76-year-old President Nursultan Nazarbayev brought to power a government that opposed Russian policy in the area? Would Russia choose to intervene, as it did in Crimea and Donbass? How would major powers react to a wave of terrorist attacks perpetrated by some of the 4000 Central Asian jihadist foreign fighters returning to their homeland, or a breakdown of public order in Tajikistan? Lastly, will Central Asia be the stage of a new “Great Game” between a waning Russia and waxing China?

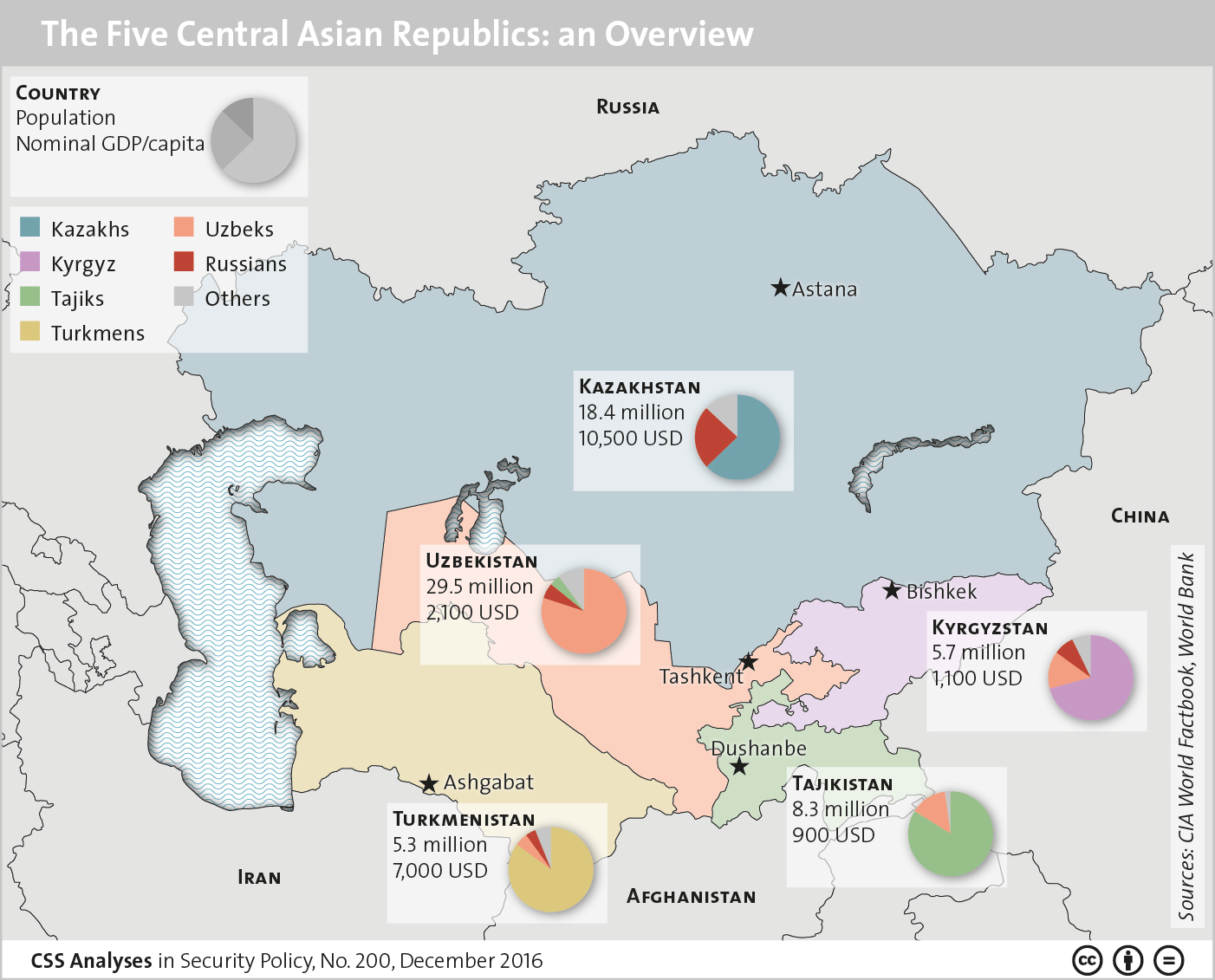

The Five Central Asian Republics: An Overview

Introducing the “Stans”

Two features help understand Central Asia: its geography and its Soviet legacy. They shape the countries’ economies as well as systems and styles of government. In terms of geography, Central Asia comprises the five former Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Together, they govern a rapidly growing population, currently estimated at 67 million. The region is the most landlocked in the world and covers a landmass from vast deserts and steppes to some of the world’s highest mountains. It is situated along the ancient Silk Road between Europe and East Asia, and it is thus often referred to as the heart of “Eurasia”. The region is rich in oil deposits, particularly in Kazakhstan, and gas reserves, as in Turkmenistan. The two smallest republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are mountainous and least resource-endowed among the “Stans”.

As a remnant of their Soviet past, large parts of Central Asian economies are state-controlled, cumbersome, and lacking diversification. The region’s poorest countries, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are the world’s first and fifth most remittance-dependent countries respectively, with a large share of their labor force working in Russia. Nevertheless, over the past two decades, average economic growth rates in Central Asia have been among the highest in the world. These successes are tempered somewhat by a sharp slump since 2014, due to the economic crisis in Russia and dropping commodity prices.

The political system of the Soviet Union has largely been preserved throughout Central Asia. The predominantly Sunni states are secular. The prevalent practice of Islam in Central Asia is moderate, and radical ideology will not hold broad appeal in the near future. With the exception of democratic but turbulent Kyrgyzstan, strong autocratic leaders are in power: President Nazarbayev has led Kazakhstan since its independence; Tajikistan’s Emomali Rahmon has held office since the end of the civil war in 1997; Turkmenistan experienced a smooth succession in 2006 and continues to be a totalitarian state under Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov; and Uzbekistan has been undergoing a succession process since September 2016. These leaders oversee state systems marred by corruption, human rights abuses, and an inability to reform. They control informal networks of power and nepotism, which in turn further weaken formal state institutions. Despite recent improvements, all Central Asian countries rank among the world’s bottom third in terms of corruption. Education systems lack funding or are abused for indoctrination purposes. Wealth is distributed unevenly, and prospects for social advancement of the growing population look dim across Central Asia.

All Central Asian republics, save for Kyrgyzstan, are republics by name only. Elections are largely a farce. Organized opposition is virtually non-existent. Occasionally, resistance has flared up in the form of Islamist terrorism. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan has executed several deadly bombings since its creation in the 1990s, and recently pledged allegiance to the “Islamic State” from its current base in Pakistan. In 2016, Kazakhstan experienced two allegedly Islamist terrorist attacks. The risk of further attacks emanates from both homegrown radicalization as well as global jihadism. An estimated 4000 foreign fighters from across Central Asia have been fighting in Syria and Iraq since 2012, and hundreds of them have returned. The threat of Islamist terrorism is a primary concern of Central Asian governments and is used to justify repression.

The line of succession is not officially defined in any of the authoritarian republics, which can create further instability in the turbulent times following a leader’s death. In September 2016, Uzbekistan’s President Karimov died. Prime Minister Mirziyoyev prevailed over a small group of potential successors. Major changes in the style of leadership and governance are unlikely. Following the widely publicized death of a long-term head of state, all other authoritarian Central Asian republics introduced legislation concerning succession. Turkmenistan extended presidential terms and lifted the president’s age limit, Tajikistan lowered the president’s minimum age to enable a dynasty, and Kazakhstan reshuffled its cabinet supposedly to put successors in place. Successors will have to satisfy different clans, economic elites, and the security sector. Considering the countries’ weak institutions and the prevalence of the patriarchy, any successor is likely to be another strongman from inside the system.

Regional (Non)Cooperation

Central Asia shares a common Soviet past and similar systems of government, and Russian is widely spoken as a lingua franca. As such, one could assume a certain degree of interconnectedness between the nations, a common interest among the elites in maintaining order, or even a unifying Eurasian identity. However, bilateral relations are poor, mistrust is high and intra-regional trade is low. Uzbekistan, as Central Asia’s most populous and most militarily powerful country, is at the center of these regional tensions. It is at odds with all its neighbors concerning border demarcation, and with upstream countries about their construction of hydroelectric dams. Sufficient access to water for growing populations will become even more of a flashpoint for tensions in the future. Of further concern are ethnic disputes, exemplified by the 2010 events in southern Kyrgyzstan. Clashes along ethnic lines left roughly 2000 people dead and caused the displacement of several hundred thousand people, largely Uzbeks.

There are multilateral institutions who could have proved useful in the face of such a crisis. A mission of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) was dismissed at an early stage. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a regional security and economic framework including both Russia and China, did not act. The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) proved to be an emperor with no clothes when the Kyrgyz request for help faced opposition from several member states. An oft-repeated justification for international abstention was that the 2010 events were a domestic issue.

The most far-reaching multilateral organization in Central Asia is the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which created a single market between Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. These two Central Asian members hoped to serve as a vibrant geopolitical bridge between East Asia and Europe. Progress in this regard has been limited, however, and they are dissatisfied with the current record and trajectory of the EAEU, as well as the fact that Russia is seen to treat the other members as junior partners.

Geopolitical Shifts

Russia, China, the US, and Europe – and to a lesser extent Turkey and Iran – are all actors that retain influence at the heart of “Eurasia”. Russia is the primary and most committed power, notably in the hard security realm. Moscow is interested in a stable “near abroad” and in preventing Central Asia from becoming an independent energy supplier to Europe, and treats Central Asia as within its undisputed sphere of influence. Defense ties with the republics are strong and genuine, especially with the CSTO members Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, which all host Russian military bases. Over the past decade, Chinese involvement in the region has grown significantly, particularly economically. It is now the region’s primary trading partner, ahead of the EU and Russia, and increases its leverage through loans and investments as part of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative (see CSS Analyses No. 195). Central Asian elites generally welcome Chinese investments, while large parts of the population are suspicious of Chinese domination and the influx of Chinese workers.

The United States’ “New Silk Road” initiative to connect Afghanistan to Central Asia has hardly materialized on the ground, and the EU’s Central Asia strategies since 2007 have had even less impact. To support the Afghanistan mission, the West de- pended on three military bases in the region, all of which had fostered close ties with the host regimes. Since NATO’s Afghanistan campaign was largely concluded by 2014, there is more room for less politicized, less securitized Western engagement. The West, Russia and China cooperate with Central Asian security services to support short-term regional stability. By engaging in this manner, these foreign powers risk further enhancing the corrupt rulers’ repressive capacities. As stability achieved through oppression is ultimately unsustainable, volatility can increase.

Two features help understand Central Asia: its geography and its Soviet legacy. They shape the countries’ economies as well as systems and styles of government. In terms of geography, Central Asia comprises the five former Soviet republics: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Together, they govern a rapidly growing population, currently estimated at 67 million. The region is the most landlocked in the world and covers a landmass from vast deserts and steppes to some of the world’s highest mountains. It is situated along the ancient Silk Road between Europe and East Asia, and it is thus often referred to as the heart of “Eurasia”. The region is rich in oil deposits, particularly in Kazakhstan, and gas reserves, as in Turkmenistan. The two smallest republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are mountainous and least resource-endowed among the “Stans”.

As a remnant of their Soviet past, large parts of Central Asian economies are state-controlled, cumbersome, and lacking diversification. The region’s poorest countries, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are the world’s first and fifth most remittance-dependent countries respectively, with a large share of their labor force working in Russia. Nevertheless, over the past two decades, average economic growth rates in Central Asia have been among the highest in the world. These successes are tempered somewhat by a sharp slump since 2014, due to the economic crisis in Russia and dropping commodity prices.

The political system of the Soviet Union has largely been preserved throughout Central Asia. The predominantly Sunni states are secular. The prevalent practice of Islam in Central Asia is moderate, and radical ideology will not hold broad appeal in the near future. With the exception of democratic but turbulent Kyrgyzstan, strong autocratic leaders are in power: President Nazarbayev has led Kazakhstan since its independence; Tajikistan’s Emomali Rahmon has held office since the end of the civil war in 1997; Turkmenistan experienced a smooth succession in 2006 and continues to be a totalitarian state under Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov; and Uzbekistan has been undergoing a succession process since September 2016. These leaders oversee state systems marred by corruption, human rights abuses, and an inability to reform. They control informal networks of power and nepotism, which in turn further weaken formal state institutions. Despite recent improvements, all Central Asian countries rank among the world’s bottom third in terms of corruption. Education systems lack funding or are abused for indoctrination purposes. Wealth is distributed unevenly, and prospects for social advancement of the growing population look dim across Central Asia.

All Central Asian republics, save for Kyrgyzstan, are republics by name only. Elections are largely a farce. Organized opposition is virtually non-existent. Occasionally, resistance has flared up in the form of Islamist terrorism. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan has executed several deadly bombings since its creation in the 1990s, and recently pledged allegiance to the “Islamic State” from its current base in Pakistan. In 2016, Kazakhstan experienced two allegedly Islamist terrorist attacks. The risk of further attacks emanates from both homegrown radicalization as well as global jihadism. An estimated 4000 foreign fighters from across Central Asia have been fighting in Syria and Iraq since 2012, and hundreds of them have returned. The threat of Islamist terrorism is a primary concern of Central Asian governments and is used to justify repression.

The line of succession is not officially defined in any of the authoritarian republics, which can create further instability in the turbulent times following a leader’s death. In September 2016, Uzbekistan’s President Karimov died. Prime Minister Mirziyoyev prevailed over a small group of potential successors. Major changes in the style of leadership and governance are unlikely. Following the widely publicized death of a long-term head of state, all other authoritarian Central Asian republics introduced legislation concerning succession. Turkmenistan extended presidential terms and lifted the president’s age limit, Tajikistan lowered the president’s minimum age to enable a dynasty, and Kazakhstan reshuffled its cabinet supposedly to put successors in place. Successors will have to satisfy different clans, economic elites, and the security sector. Considering the countries’ weak institutions and the prevalence of the patriarchy, any successor is likely to be another strongman from inside the system.

Regional (Non)Cooperation

Central Asia shares a common Soviet past and similar systems of government, and Russian is widely spoken as a lingua franca. As such, one could assume a certain degree of interconnectedness between the nations, a common interest among the elites in maintaining order, or even a unifying Eurasian identity. However, bilateral relations are poor, mistrust is high and intra-regional trade is low. Uzbekistan, as Central Asia’s most populous and most militarily powerful country, is at the center of these regional tensions. It is at odds with all its neighbors concerning border demarcation, and with upstream countries about their construction of hydroelectric dams. Sufficient access to water for growing populations will become even more of a flashpoint for tensions in the future. Of further concern are ethnic disputes, exemplified by the 2010 events in southern Kyrgyzstan. Clashes along ethnic lines left roughly 2000 people dead and caused the displacement of several hundred thousand people, largely Uzbeks.

There are multilateral institutions who could have proved useful in the face of such a crisis. A mission of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) was dismissed at an early stage. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a regional security and economic framework including both Russia and China, did not act. The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) proved to be an emperor with no clothes when the Kyrgyz request for help faced opposition from several member states. An oft-repeated justification for international abstention was that the 2010 events were a domestic issue.

The most far-reaching multilateral organization in Central Asia is the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which created a single market between Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. These two Central Asian members hoped to serve as a vibrant geopolitical bridge between East Asia and Europe. Progress in this regard has been limited, however, and they are dissatisfied with the current record and trajectory of the EAEU, as well as the fact that Russia is seen to treat the other members as junior partners.

Geopolitical Shifts

Russia, China, the US, and Europe – and to a lesser extent Turkey and Iran – are all actors that retain influence at the heart of “Eurasia”. Russia is the primary and most committed power, notably in the hard security realm. Moscow is interested in a stable “near abroad” and in preventing Central Asia from becoming an independent energy supplier to Europe, and treats Central Asia as within its undisputed sphere of influence. Defense ties with the republics are strong and genuine, especially with the CSTO members Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, which all host Russian military bases. Over the past decade, Chinese involvement in the region has grown significantly, particularly economically. It is now the region’s primary trading partner, ahead of the EU and Russia, and increases its leverage through loans and investments as part of its One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative (see CSS Analyses No. 195). Central Asian elites generally welcome Chinese investments, while large parts of the population are suspicious of Chinese domination and the influx of Chinese workers.

The United States’ “New Silk Road” initiative to connect Afghanistan to Central Asia has hardly materialized on the ground, and the EU’s Central Asia strategies since 2007 have had even less impact. To support the Afghanistan mission, the West de- pended on three military bases in the region, all of which had fostered close ties with the host regimes. Since NATO’s Afghanistan campaign was largely concluded by 2014, there is more room for less politicized, less securitized Western engagement. The West, Russia and China cooperate with Central Asian security services to support short-term regional stability. By engaging in this manner, these foreign powers risk further enhancing the corrupt rulers’ repressive capacities. As stability achieved through oppression is ultimately unsustainable, volatility can increase.

Switzerland and Central Asia

Switzerland has supported political transition processes in Central Asia since the early 1990s. In Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Switzerland supports vocational education, public sector reform, private sector development, and initiatives around health and strengthening the rule of law. Across the region, Switzerland is focused on addressing one source of great political and ethnic tension: water management. Funding for Swiss cooperation in Central Asia amounted to 200 million CHF between 2012 and 2015.

Since 1992, Switzerland has led a constituency group in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund that includes all five Central Asian republics, which the media nicknamed “Helvetistan”. Leadership of this group grants Switzerland a seat on the organizations’ executive boards.

Central Asia also provides a further source of Swiss energy. Though levels vary over the years, Switzerland imports up to one third of its crude oil from Kazakhstan.

The daughter of the former Uzbek president, Gulnara Karimova, and other members of the Uzbek elite laundered vast assets using Swiss bank accounts. Since 2012, an implicated sum of 800 million CHF has been blocked and remains disputed.

Switzerland has supported political transition processes in Central Asia since the early 1990s. In Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Switzerland supports vocational education, public sector reform, private sector development, and initiatives around health and strengthening the rule of law. Across the region, Switzerland is focused on addressing one source of great political and ethnic tension: water management. Funding for Swiss cooperation in Central Asia amounted to 200 million CHF between 2012 and 2015.

Since 1992, Switzerland has led a constituency group in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund that includes all five Central Asian republics, which the media nicknamed “Helvetistan”. Leadership of this group grants Switzerland a seat on the organizations’ executive boards.

Central Asia also provides a further source of Swiss energy. Though levels vary over the years, Switzerland imports up to one third of its crude oil from Kazakhstan.

The daughter of the former Uzbek president, Gulnara Karimova, and other members of the Uzbek elite laundered vast assets using Swiss bank accounts. Since 2012, an implicated sum of 800 million CHF has been blocked and remains disputed.

Acute Crises

Central Asia’s most severe problems emanate from low commodity prices and the Russian economic crisis in the wake of Western sanctions. These two dynamics created negative repercussions on all Central Asian republics, albeit in different ways. Turkmenistan’s economy is dominated by its dependence on gas rents. The state has not been able to pay some of its civil servants, even police, for months. Kazakhstan relies heavily on oil and gas revenues, and faces increased Russian economic competition due to the weaker ruble. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and to a lesser extent Uzbekistan, vitally depend on Russian aid and loans, and on remittances. Transfers are estimated to have at least halved since the invasion of Crimea, and hundreds of thousands of migrant workers have lost their jobs and returned home.

To cope with such shocks and increasing demographic pressure, Central Asian states require tough reforms: spending cuts and both the liberalization and diversification of the economy. Yet general sluggishness and the much-praised political stability hinder transformation. Reforms would face strong resistance, likely emanating from disaffected members of the elite attempting to protect their shrinking assets. Obstructions such as these could threaten the era of relative calm in Central Asia. Considering the limited organized opposition, civil society and free press, popular movements are less likely to occur, except if major events or external shocks act as catalysts. The economic crisis or the accentuation of major geopolitical rivalries could serve as such catalysts.

In view of recent Taliban attacks in Kunduz and throughout northern Afghanistan, Central Asian leaders as well as Russia, China and the West increasingly worry about an incursion into Tajikistan. Actors vividly remember Tajikistan’s brutal civil war that ended in 1997, during which many attacks were staged from Afghanistan. Up to a third of Afghanistan’s narcotics production is trafficked across Tajikistan’s porous borders. Exacerbated by these tensions, order in Tajikistan may break down in the near future. Like most cases of state collapse, the main causes would be internal however. The Tajik government is kleptocratic, incompetent and divided, and security forces are weak. The economy is ailing, offering few prospects to returning migrant workers. Discontent is mounting after President Rahmon manipulated the election in 2015 and banned the main opposition party, thus violating the power sharing agreement of 1997. In the face of looming state collapse, the 7000 Russian troops based in Tajikistan may not stand idly by. Even China, whose troublesome Xinjiang province borders Tajikistan, may consider engaging, though this would contradict their current position in support of non-intervention.

Crimea in the Steppe?

Since 2014, the Crimean invasion has represented an elephant in the room for Central Asian states. Events in Ukraine spooked elites across Central Asia for two reasons. First, regime change following popular protests is not a phenomenon they would like to see repeated in the region.

Second, the annexation of Crimea and involvement in Eastern Ukraine, in direct violation of international law, made them wary of their Russian ally. The republics are already pursuing a multi-vector foreign policy to balance the influence of major powers and to emphasize their sovereignty.

Russia is perhaps most invested in retaining influence in Kazakhstan. It is relatively stable and prosperous, with a popular ruler and nascent civil society and economic diversity. Observers have voiced concern that northern Kazakhstan, or “southern Siberia” as some Russian nationalists call it, could become a new Crimea or Donbass. The parallels with Ukraine are staggering. In Ukraine, Vladimir Putin violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which also guarantees Kazakhstan’s borders. Northern Kazakhstan has a large ethnic-Russian population, the Russian language is prevalent throughout the country, and Russian media actually dominate across Kazakhstan. The government has to balance the interests of Kazakh nationalists with ethnic minorities. In a 2014 speech, Putin shocked Nazarbayev claiming Kazakhstan as an integral part of the Russian sphere of influence and negating Kazakh statehood before 1991. An intervention similar to the one that took place in Ukraine, however, remains quite unlikely. Kazakhstan cannot and will not break its genuine alliance with Russia. There is not a strong enough inducement from the EU, NATO or China to encourage such a step. Unlike in Crimea, Russia has no strong historic and cultural claim to northern Kazakhstan. There is no Russian interest to destabilize 7000 km of border with a weak Kazakhstan following a Donbass scenario either.

Nevertheless, some events could trigger a harsh Russian response, for example if Kazakhstan were to leave the EAEU – which it indicated was a possibility if the economic organization becomes primarily a political project – or if a highly nationalist or anti-Russian Kazakhstani government threatens Russian interests. With few allies and a relatively weak military, Kazakhstan would have no means of resistance. As such, Kazakhstan is both a major ally of Russia and a hostage to Russian foreign policy.

Geopolitically, Russia, China, and possibly the US may increasingly struggle for influence in Central Asia. There is, however, currently no sign of such a new “Great Game”. Central Asia is too peripheral, particularly for the US, to serve as a stage of geopolitics. Particularly in the face of strict Western sanctions, Russia is ever more dependent on cooperation and its “marriage of convenience” with China, despite mutual distrust.

In the long run, however, Chinese economic influence will eventually translate into political influence. One could imagine a scenario in which a powerful China forces a weakened Russia to give way to its ambitions in Central Asia without the use of arms, and claims it as part of China’s sphere of influence, as the back yard of its troublesome Xinjiang province. The newly-won Chinese supremacy and corresponding loss of influence for Russia would certainly trigger regional instability. As it stands, China is satisfied with the stable security environment, consistent access to energy, and sufficient economic leverage over Central Asia.

Despite its strong commitment to the region, Russia’s current crisis reduces possible incentives and the capacity for intervention to keep the republics in line. Even without increased Chinese assertiveness, to a certain extent Russia’s influence in Central Asia is bound to decline.

About the Author

Benno Zogg is Researcher at the Think Tank of the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. His areas of research interest include the post-Soviet and development and security in fragile contexts

Central Asia’s most severe problems emanate from low commodity prices and the Russian economic crisis in the wake of Western sanctions. These two dynamics created negative repercussions on all Central Asian republics, albeit in different ways. Turkmenistan’s economy is dominated by its dependence on gas rents. The state has not been able to pay some of its civil servants, even police, for months. Kazakhstan relies heavily on oil and gas revenues, and faces increased Russian economic competition due to the weaker ruble. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and to a lesser extent Uzbekistan, vitally depend on Russian aid and loans, and on remittances. Transfers are estimated to have at least halved since the invasion of Crimea, and hundreds of thousands of migrant workers have lost their jobs and returned home.

To cope with such shocks and increasing demographic pressure, Central Asian states require tough reforms: spending cuts and both the liberalization and diversification of the economy. Yet general sluggishness and the much-praised political stability hinder transformation. Reforms would face strong resistance, likely emanating from disaffected members of the elite attempting to protect their shrinking assets. Obstructions such as these could threaten the era of relative calm in Central Asia. Considering the limited organized opposition, civil society and free press, popular movements are less likely to occur, except if major events or external shocks act as catalysts. The economic crisis or the accentuation of major geopolitical rivalries could serve as such catalysts.

In view of recent Taliban attacks in Kunduz and throughout northern Afghanistan, Central Asian leaders as well as Russia, China and the West increasingly worry about an incursion into Tajikistan. Actors vividly remember Tajikistan’s brutal civil war that ended in 1997, during which many attacks were staged from Afghanistan. Up to a third of Afghanistan’s narcotics production is trafficked across Tajikistan’s porous borders. Exacerbated by these tensions, order in Tajikistan may break down in the near future. Like most cases of state collapse, the main causes would be internal however. The Tajik government is kleptocratic, incompetent and divided, and security forces are weak. The economy is ailing, offering few prospects to returning migrant workers. Discontent is mounting after President Rahmon manipulated the election in 2015 and banned the main opposition party, thus violating the power sharing agreement of 1997. In the face of looming state collapse, the 7000 Russian troops based in Tajikistan may not stand idly by. Even China, whose troublesome Xinjiang province borders Tajikistan, may consider engaging, though this would contradict their current position in support of non-intervention.

Crimea in the Steppe?

Since 2014, the Crimean invasion has represented an elephant in the room for Central Asian states. Events in Ukraine spooked elites across Central Asia for two reasons. First, regime change following popular protests is not a phenomenon they would like to see repeated in the region.

Second, the annexation of Crimea and involvement in Eastern Ukraine, in direct violation of international law, made them wary of their Russian ally. The republics are already pursuing a multi-vector foreign policy to balance the influence of major powers and to emphasize their sovereignty.

Russia is perhaps most invested in retaining influence in Kazakhstan. It is relatively stable and prosperous, with a popular ruler and nascent civil society and economic diversity. Observers have voiced concern that northern Kazakhstan, or “southern Siberia” as some Russian nationalists call it, could become a new Crimea or Donbass. The parallels with Ukraine are staggering. In Ukraine, Vladimir Putin violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which also guarantees Kazakhstan’s borders. Northern Kazakhstan has a large ethnic-Russian population, the Russian language is prevalent throughout the country, and Russian media actually dominate across Kazakhstan. The government has to balance the interests of Kazakh nationalists with ethnic minorities. In a 2014 speech, Putin shocked Nazarbayev claiming Kazakhstan as an integral part of the Russian sphere of influence and negating Kazakh statehood before 1991. An intervention similar to the one that took place in Ukraine, however, remains quite unlikely. Kazakhstan cannot and will not break its genuine alliance with Russia. There is not a strong enough inducement from the EU, NATO or China to encourage such a step. Unlike in Crimea, Russia has no strong historic and cultural claim to northern Kazakhstan. There is no Russian interest to destabilize 7000 km of border with a weak Kazakhstan following a Donbass scenario either.

Nevertheless, some events could trigger a harsh Russian response, for example if Kazakhstan were to leave the EAEU – which it indicated was a possibility if the economic organization becomes primarily a political project – or if a highly nationalist or anti-Russian Kazakhstani government threatens Russian interests. With few allies and a relatively weak military, Kazakhstan would have no means of resistance. As such, Kazakhstan is both a major ally of Russia and a hostage to Russian foreign policy.

Geopolitically, Russia, China, and possibly the US may increasingly struggle for influence in Central Asia. There is, however, currently no sign of such a new “Great Game”. Central Asia is too peripheral, particularly for the US, to serve as a stage of geopolitics. Particularly in the face of strict Western sanctions, Russia is ever more dependent on cooperation and its “marriage of convenience” with China, despite mutual distrust.

In the long run, however, Chinese economic influence will eventually translate into political influence. One could imagine a scenario in which a powerful China forces a weakened Russia to give way to its ambitions in Central Asia without the use of arms, and claims it as part of China’s sphere of influence, as the back yard of its troublesome Xinjiang province. The newly-won Chinese supremacy and corresponding loss of influence for Russia would certainly trigger regional instability. As it stands, China is satisfied with the stable security environment, consistent access to energy, and sufficient economic leverage over Central Asia.

Despite its strong commitment to the region, Russia’s current crisis reduces possible incentives and the capacity for intervention to keep the republics in line. Even without increased Chinese assertiveness, to a certain extent Russia’s influence in Central Asia is bound to decline.

About the Author

Benno Zogg is Researcher at the Think Tank of the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. His areas of research interest include the post-Soviet and development and security in fragile contexts

No comments:

Post a Comment