The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey

Bridging gaps in US-Iran talks is easier said

than done

By James M. Dorsey

Thank you for joining me today. Your support and loyalty mean a lot

to me. It allows me to maintain and expand this column and podcast.

Without you, I would not be able to offer an original perspective to

an ever more important discussion of what the world should and will

look like in the 21st century with a focus on the Middle East and the

Muslim world in evolving geopolitics.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber and urging your friends

and colleagues to do the same.

Thank you and best wishes.

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi (left) meets his Turkish counterpart, Hakan Fidan, in Ankara days before US-Iran talks

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has some advice for US negotiators in advance of Friday’s US-Iranian talks in Oman aimed at avoiding a military conflagration that could spark a regional war in the Middle East.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, Mr. Fidan suggested that the US tackle one contentious issue at a time rather than seek a package deal that addresses all US demands, starting with curbs on Iran’s nuclear programme.

“My advice to our American friends is, close the files one by one. Start with nuclear. Close it. Then the other, then the other, then the other. If you put them as a package, it will be very difficult for our Iranian friends to digest and really process it,” Mr. Fidan said days after talks with his Iranian counterpart, Abbas Araghchi.

Turkey, together with Qatar, has played a key role in attempts to avert a military conflagration as US President Donald Trump, threatening to attack Iran if the talks fail, amasses an armada in the Middle East.

Talks between the United States and Iran over the nuclear issue broke down last June when Israel waged

a 12-day air campaign against Iran and the United States bombed three of the country’s nuclear facilities.

Iran insists on its right to enrich uranium to 3.67 per cent as stipulated in the 2015 international agreement that curbed the Islamic Republic’s nuclear programme.

Mr. Trump unilaterally walked away from that agreement in 2018 during his first term in office. In response, Iran gradually enriched an estimated 400 kilogrammes of uranium to 60 per cent purity, a short step away from

the 90 per cent weapons-grade level.

It’s unclear whether or how much of the enriched uranium the US strikes destroyed, despite Mr. Trump’s repeated claims that Iran’s nuclear capabilities were “obliterated.”

Mr. Trump wants Iran to surrender whatever may be left of the highly enriched uranium.

Mr. Fidan’s phased approach to US-Iran negotiations may be an opportunity for both parties to agree on

a mutually acceptable face-saving solution, given that compromise on the United States’ other demands, including curbs on the Islamic Republic’s ballistic missile programme and support for non-state allies in Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen, is more difficult.

Iran has long declared that its support for Lebanese Shiite militia and political movement Hezbollah,

Yemen’s Houthi rebels, and Iraqi Shiite militias, and its ballistic missile programme is non-negotiable,

even though Israel has significantly degraded the Lebanese group’s military capability.

Iran has also rejected a US demand that it release thousands arrested during the recent weeks-long protests sparked by the country’s worsening economic crisis.

The core of Iran’s defence capabilities, ballistic missiles, are particularly sensitive, given that the country

doesn’t have a credible air force or navy. No Iranian government, whether revolutionary or post-revolution, would be willing to limit its missile programme.

As a result, neither the United States nor Iran has much room to manoeuvre beyond resolving the nuclear

issue.

With Mr. Trump’s armada in the Middle East, in the belief that Iran will either voluntarily or by force capitulate, and the United States and Iran reverting to bellicose rhetoric, the risk is that they each have boxed themselves into a corner from which it may be difficult to escape.

Saudi Defence Minister Khalid bin Salman conceded as much when he last week seemed to resign himself to the inevitable.

Rather than endorsing a US military intervention, Mr. Bin Salman told a private gathering of think tank

analysts and representatives of American Jewish organisations in Washington that the administration had

left itself no good options.

“At this point, if this doesn’t happen, it will only embolden the regime,” Mr. Bin Salman said, referring to

US military action.

He may have a point, depending on the nature and outcome of potential US strikes that would likely target, among others, Iran’s powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC, or the degree to which Iran

bows to US demands to avert intervention.

The IRGC and its Basij voluntary militia are among the prime targets the US military has presented to Mr. Trump.

Without a resolution of at least the nuclear issue, the more likely prospect is that both the United States and Iran are doomed if they do and doomed if they don’t, which enhances the spectre of a region-wide war, involving not only Israel and the Gulf, but, possibly, Turkey and the former Soviet republic of Azerbaijan.

With no potential US or Israeli targets within its borders and limited capability to hit US facilities further afar, Iran would have to respond to an American attack with strikes against Israel, US military bases and critical infrastructure in the Gulf, and/or international shipping in Gulf waters.

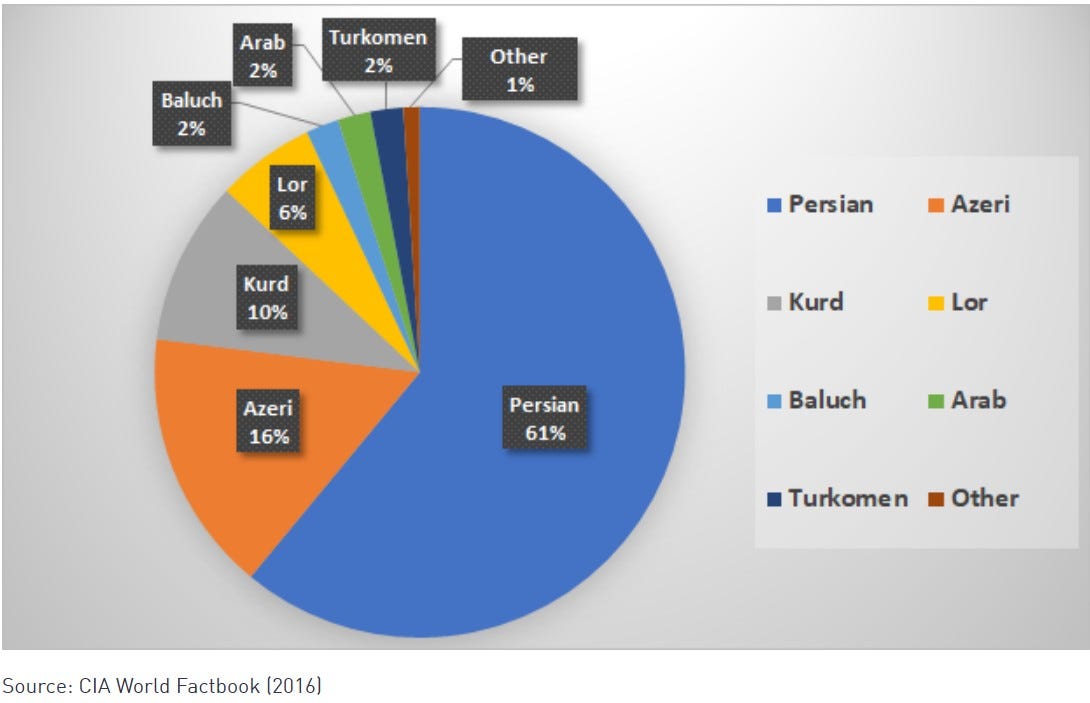

While Iran is unlikely to attack Turkey’s Incirlik Airbase that hosts the US military’s 39th Air Base Wing, an uptick of ethnic nationalism, particularly among Azeris, a Turkic group who account from anywhere between 16 and 24 per cent of the Iranian population, could draw Turkey and neighbouring Azerbaijan into a wider regional conflict on the principle of ‘you may not want war but war wants you.’

Proponents of a US attack have advocated a US targeting of Azeri units of the IRGC, which they describe as the Guards’ most brutal. The Guards were responsible for the government’s violent crackdown on the protesters.

Among Iran’s ethnic and religious minorities, who account for approximately 43 per cent of the Iranian population, Azeris are the most integrated and have risen to high government positions. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is part Azeri.

The proponents hope that targeting Azeri units will spark ethnic unrest, also among Iran’s other Kurdish, Arab, Baloch, Turkmen, and Lors minorities, who, like the Azeris, straddle the country’s borders. Israel and the United States have, at times, supported militant Kurdish and Baloch militants.

The Trump administration and Israel may not consider a fracturing of Iran as a bad thing.

Israel and some in the administration and Mr. Trump’s support base believe the fracturing of Israel’s neighbours and enemies enhances Israel’s security, a school of thought that resonates with some within the Washington Beltway.

Discussing recent cases of potential secession or greater autonomy in Yemen, Somalia, and Syria, and whether in an era of transition in the world order, the borders of nation-states should be sacrosanct, scholar Steven A. Cook concluded, “Sometimes they are, but not always.”

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an Adjunct Senior Fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Associate Editor of WhoWhatWhy, and the author of the syndicated column and podcast, The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey.

No comments:

Post a Comment