|  | | with Sammy Westfall |

Over the past year, The Washington Post has tracked how governments, including both democracies and autocracies, have used assets and agents abroad to track, silence and even kill political opponents. We looked, among other cases, at how China cracked down on protesters in San Francisco, how Iran recruited assassins among the Hells Angels biker gang and how Rwanda has stalked the families of dissidents abroad. The newsletter today is a compilation of this sprawling reporting project by my colleagues. The stories here reveal an emerging dark side in 21st century politics, as growing powers violate the sovereignty of other states for repressive aims. It reflects a shift in global norms and behavior arguably started by the United States, which, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, launched covert surveillance and counterterrorism operations around the world. |

| (Illustration by Rob Dobi for The Washington Post) |

ANKARA, Turkey — As abduction teams fanned out across neighborhoods in Nairobi in October, their targets — members of a Turkish religious movement — seemed to have few worries beyond the hassles of a hectic weekday. One was returning from a visa appointment with his family; a second was at the motor vehicle office for a driving test; still others were trying to beat traffic during the early Friday commute. By morning’s end, seven Turkish nationals had been abducted at gunpoint, hooded and handcuffed by masked agents traveling in unmarked vehicles, according to Western security officials, witnesses and relatives of the victims. While three were later released, four were taken to a remote airstrip outside the Kenyan capital, officials said, and forced aboard a plane waiting to take them to a Turkish prison near here. The abductions were the latest of more than 118 “renditions” that Turkey’s intelligence service, MIT, has orchestrated over the past decade, according to the spy agency’s website, making it one of the most aggressive practitioners of such extralegal operations. In Nairobi, MIT relied on Kenyan government operatives to carry out the abductions and was able to bypass Kenyan courts, according to the Western security officials who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive operation. Turkey has branded this global campaign its own “war on terror” in an echo of the phrase that came to define the period after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks in the United States. Turkey has also drawn extensively from the U.S. counterterrorism playbook. Beyond renditions, it has used secret detentions, terrorism watch lists, asset seizures and torture — including at least one reported case of waterboarding — against exiles, according to U.N. documents, human rights groups, Western security officials and public records in Turkey. These operations have been “justified in the name of combating terrorism,” according to a U.N. report, even though nearly all those targeted are members of a religious sect known as the Gulen movement with no history of terrorist attacks. Turkey has labeled the group a terrorist organization because of its members’ alleged involvement in a failed 2016 coup. But the United States and other governments have rejected this designation, and the movement has not been accused of acquiring explosives, plotting attacks against civilians or other activities associated with terrorism. This article includes previously unreported details about Turkey’s rendition operations and its reliance on counterterrorism capabilities to target exiles. It is based on dozens of interviews with Western, Turkish and other government officials, U.N. advisers and human rights experts, as well as victims of abductions and their relatives and associates. The Washington Post also relied on Turkish court records, U.N. documents and other materials. Turkish officials defended the country’s campaign against the Gulen movement, saying that the Turkish government abides by legal processes — including arrest warrants and criminal trials — that the United States often bypassed in its own operations against terrorist groups. “This is a terrorist organization,” a senior Turkish official said in an interview here, adding that the government apprehends members overseas and returns them to Turkey “because it is important for them to be judged here.” Kenyan officials, including a representative of the office of the president, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Turkey’s attempt to characterize this crackdown as counterterrorism is seen by human rights organizations and Western security officials as an attempt to legitimize a campaign of transnational repression, a term for governments’ use of violence and intimidation against exiles seen as a political threat. |

|

Mourners carry the casket of Turkish Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen after a funeral prayer service at Skylands Stadium in Augusta, New Jersey, on Oct. 24. Gulen, who was accused by Turkey of organizing a failed 2016 coup, died in exile in the United States on Oct. 20. (Leonardo Munoz/AFP/Getty Images) |

In doing so, Turkey is part of a broader phenomenon. Global powers and autocratic leaders have applied the terrorist label to an expanding array of exiled groups and cast operations against them — including assassinations and abductions — as a continuation of the post-9/11 struggle. China has applied the term to members of the Uyghur religious minority; India to Sikh separatists; Iran to journalists and women’s rights activists; Vietnam to Christian dissidents; and Rwanda to opposition figures — to cite only some of the countries now routinely branding critics living outside their borders as terrorists. They have done so in part to exploit the pejorative power of a term that has no internationally agreed-upon definition, but also to justify their manipulation of a global counterterrorism apparatus that enables them to seize assets, track travel and capture supposed suspects, international monitors said. The post-9/11 efforts of Washington and its allies largely succeeded in dismantling al-Qaeda and preventing further attacks in the United States. But in straying from long-standing laws and norms, the campaign came to be associated with targeted killings by drone, CIA black sites and torture, indefinite detention without trial at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the brutalization of prisoners by the U.S. military at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, and the United States’ own rendition operations around the globe. After 9/11, the United States was “driving a completely legitimate set of objectives,” said Juan Zarate, who served as a senior counterterrorism official in the George W. Bush administration. The abuses, however, “had a corrosive effect not just on the legitimacy of what we were doing but in allowing authoritarian regimes the running room to claim that what they were doing were within the boundaries of what the West had done.” International monitors and security officials said the abuse of counterterrorism capabilities has added to the complicated legacy of the response to the Sept. 11 attacks. “Twenty-plus years after 9/11, you would anticipate a diminished” reliance on the terms and tactics associated with the war on terror, said Fionnuala Ni Aolain, who served as special rapporteur to the United Nations on counterterrorism and human rights from 2017 until last year. “Instead, what we find is a repurposing, reappropriation and acceleration of those methods by backsliding democracies and authoritarian regimes.” – Greg Miller Read the full story, and the rest of the ‘Repression’s long arm’ series: That India would pursue lethal operations in North America has stunned Western security officials. In some ways, however, it reflects a profound shift in geopolitics. – Greg Miller, Gerry Shih and Ellen Nakashima Rwanda tries to silence critics abroad by targeting relatives back home, at times arresting and torturing them, say former officials and other exiled Rwandans. – Katharine Houreld Prime Minister Narendra Modi has cast himself as more willing to take on India’s enemies beyond its borders than any other leader since independence. – Gerry Shih Iran has cultivated ties with criminal networks in the West to carry out a recent wave of violent plots in the United States and Europe. – Greg Miller, Souad Mekhennet and Cate Brown China has stepped up efforts to intimidate and spy on its diaspora, as Beijing’s influence grows outside its borders. – Shibani Mahtani, Meg Kelly, Cate Brown, Cate Cadell, Ellen Nakashima and Chris Dehghanpoor |

| Palestinian children wait to be allowed to return to their homes in northern Gaza after they were displaced to the south at Israel’s order during the war, amid a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, in the central Gaza Strip, Jan. 26. (Mohammed Salem/Reuters) |

Gazans find fragments of life along with remains of loved ones: Since the ceasefire between Hamas and Israel began a week ago, Palestinians returning to their communities are finding only fragments of their former lives. Many are also searching desperately for their missing loved ones. Ali Suleiman, a merchant from Khan Younis, last saw his teenage son nine months ago. Suleiman has spent this week searching for him in hospitals, on the streets and under the rubble, he said in a video interview, where many bodies are being recovered. “I’ll know him immediately through his clothes, even if he is a skeleton,” Suleiman said. Ahmed Radwan, a spokesperson for the Palestinian civil defense, said Thursday that his team recovered about 150 bodies from the rubble in various neighborhoods of Rafah. The bodies are so decomposed that they are hard to identify, he explained. There are still more to find. – Maham Javaid, Joe Snell, Hajar Harb and Janice Kai Chen |

| | (Illustration by James Lee Chiahan for The Washington Post) |

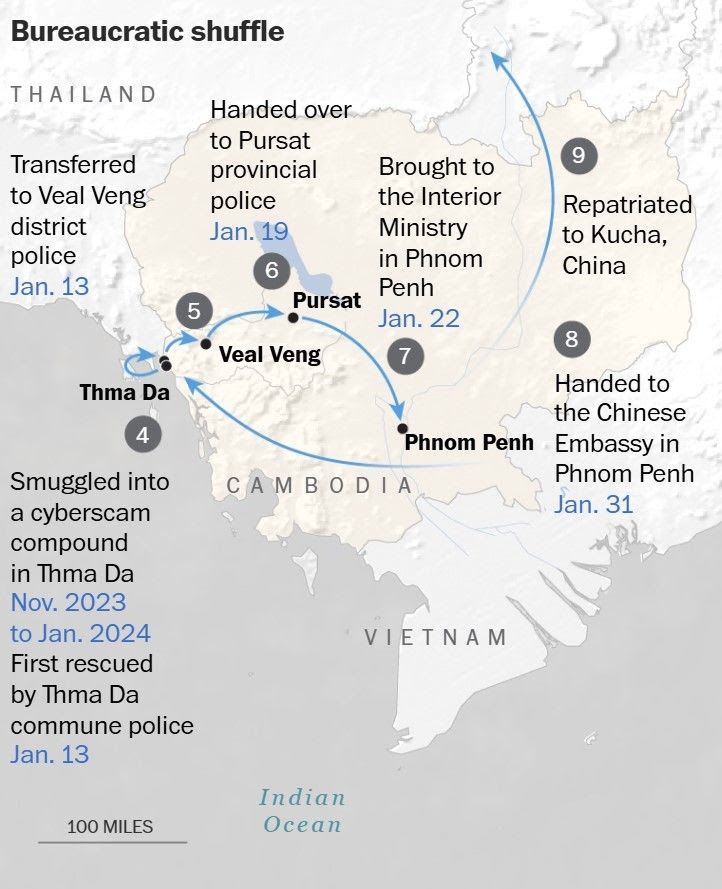

THMA DA, Cambodia — The arrival of Cambodian police officers should have come as a relief for Abdureqip Rahman. The young Uyghur man had been trapped inside a high-walled, barbed-wire compound for 10 weeks, working alongside others trafficked here and forced, often through beatings, to run online scams. But Rahman had become increasingly nervous at the prospect of rescue, wary of the Cambodian authorities. He had heard that the officers were there to take him to the capital, Phnom Penh, and then to immigration authorities who would send him home — to China, where the consequences would be “unimaginable,” he said. Rahman tried to stay calm. He reminded himself of assurances from U.N. officials that he would be protected. He was hoping ultimately to secure asylum in the United States. “Everything is okay,” a U.N. official had told him in a series of Signal messages he secretly exchanged while he was still in the scam compound. “The U.N. and other partners are involved and requesting international protection for your case.” Rahman, 23, had told officials and activists that he had worked in the massive and brutal penal system that China built in the region of Xinjiang to suppress the Uyghur Muslim population there, and then was detained after he left his job. After he fled China, his WeChat accounts and bank accounts were frozen, he said. Authorities in Xinjiang told his family they were looking for him. A Washington Post investigation found that after his removal from the compound here on Jan. 13, Rahman was held by the Cambodian authorities and then returned to China. He has not been heard from since Jan. 30. |

|

|

Rahman’s secret repatriation is a starkly chilling example of how China increasingly exerts its will extrajudicially outside its borders, not only over Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia, but also international bodies — including the United Nations, whose systems were designed to protect the world’s most vulnerable. Under international law, no one should be returned to a country where they would face torture or other inhumane treatment. The United States says there is an ongoing genocide against the Uyghur Muslim population, and in 2022, the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights said China may be responsible for crimes against humanity against the minority group. China has for years demanded the return of Uyghurs who fled to other countries, including Thailand, Egypt and Pakistan. Hundreds of Uyghurs have been extrajudicially deported since the acceleration of the crackdown against the Muslim minority in 2017, particularly from Central and Southeast Asia, North Africa and the Middle East — according to Uyghur activists and human rights reports — or are being detained indefinitely in those regions. – Shibani Mahtani Read on: He thought he had escaped Beijing’s clutches only to vanish back into China |

| |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment