Kazım Karabekir'i tanıtma notu

E. KUR. ALB. NUSRET BAYCAN

Büyük bir asker olan Korgeneral Kâzım Karabekir, koruyucu ve sevecen kişiliği

yanında, Türk ahlâk ve karakterinin de seçkin bir siması idi. Bazı eserlerde son

rütbesi Orgeneral olarak gösterilmekte ise de Genelkurmay Başkanlığının ilgili

şubesinde ve arşivdeki şahsî dosyasında bu rütbeye yükseldiğine dair bir kayıt

ve belgeye rastlanamamıştır. Esasen emekli maaşı da Ferik yani Korgeneral

rütbesi üzerindendir.

Görüş ve düşüncelerinde vatanseverliği ve milletinin selâmeti her zaman ön

plânda yer almıştır.

Mustafa Kemal Paşa (Atatürk) ile, zaman zaman askerî ve siyasî konularda

fikir ayrılıkları olmuşsa da, ilişkilerinde her zaman içtenlik ve dürüstlük

hâkimdi.

Yurt savunması ile ilgili konularda titizlik göstermesinde, katıldığı

harplerdeki maddî ve manevî kayıplarımızın ve şahidi olduğu fecaatin etkisi

büyüktür. Kâzım Karabekir, 1910 Arnavutluk Ayaklanmasının bastırılmasında önemli

rol oynamış, Balkan Harbinde Edirne Kalesini savunmuş, Birinci Dünya Harbinde

çeşitli cephelerde tümen ve kolordulara komuta etmiş, zaferler kazanmış, Türk

İstiklâl Harbinin Doğu Cephesi Komutanı olarak ün yapmıştır.

Kâzım Karabekir’in

Yaşamı:

1882’de İstanbul’da doğmuş, ilk öğrenimine burada başlamış, babası Emin

Paşa’nın görev yaptığı Van, Harput ve Mekke’de sürdürmüştür. Orta öğrenimini,

Fatih Askerî Rüştiyesi ve Kuleli Askerî Lisesinde yapmış, 1899’da Harp Okuluna

geçmiştir.

Askerî Yaşamı:

6 Aralık 1902’de Harp Okulunu ve 5 Kasım 1905’te Harp Akademisini

birincilikle bitiren Kâzım Karabekir, bu başarıları nedeniyle Altın Maarif

Madalyasıyla ödüllendirilmiştir.

Kurmay Yüzbaşı olarak 3’ncü Ordu emrine atanmış, kurmay stajını Manastır’da

yapmış, iki yıllık staj süresince bulunduğu birliklerin katıldığı çarpışmalarda

üstün başarı göstermiştir. 1907’de Kıdemli Yüzbaşı olmuş ve Beşinci Rütbeden

Mecidi Nişanı ile ödüllendirilerek İstanbul’daki Harp Okulu Tabiye Öğretmen

Yardımcılığına, 1908’de de Edirne’deki 3’üncü Tümen Kurmay Başkanlığına

atanmıştır.

31 Mart (13 Nisan 1909) Olayı üzerine Hareket Ordusu Mürettep 2’nci Tümen

Kurmay Başkanı olarak İstanbul’a gelmiş, Beyoğlu kışlaları ve Yıldız Sarayı’nın

ele geçirilmesinde görev almıştır.

1910’da Arnavutluk Ayaklanmasını bastırmak için teşkil olunan Mürettep

Kolordu’nun Harekât Şube Müdürlüğüne atanmış, bir süre Kurmay Başkan Vekilliği

de yapmıştır. Bazı çarpışmalarda müfreze komutanı olarak kazandığı başarı

nedeniyle Dördüncü Rütbeden Osmanî Nişanı ile ödüllendirilmiştir.

15 Ocak 1911’de io’ncu Tümen Kurmay Başkanlığına atanmış, 27 Nisan 1912’de

Binbaşılığa yükseltilmiştir. 22 Haziran 1913’te Edirne savunmasında Bulgarlara

esir düşmüş, 29 Eylül 1913’te yapılan İstanbul Antlaşmasından sonra yurda

dönmüştür.

9 Aralık 1914’te Yarbay olmuş, Genel Karargâh İstihbarat Şube Müdürlüğünden,

i’nci Kuvve-i Seferiye Komutanlığına atanan Kâzım Karabekir Halep’ten ayrılarak,

yaralanmış bulunan Süleyman Askeri Bey’den Irak Havalisi Komutanlığını devralmak

üzere Bağdat’a gitmiş ise de komuta değişikliğine neden kalmamış ve 6 Mart

1915’te 14’ncü Tümen Komutanlığına atanarak İstanbul’a gelmiştir. Kısa bir süre

sonra da tümeniy-le Çanakkale’ye giderek Seddülbahir muharebelerine

katılmıştır.

26 Ekim 1915’te 1’nci Ordu, 10 Kasım 1915’te 6’ncı Ordu Kurmay

Başkanlıklarına atanan Kâzım Karabekir, 14 Aralık 1915’te Albaylığa

yükseltilmiş, Çanakkale’deki başarıları nedeniyle, Harp, Gümüş Muharebe Liyakat

ve Gümüş Muharebe imtiyaz Madalyalarıyla ödüllendirilmiştir.

27 Nisan 1916’da 18’nci Kolordu Komutanlığına atanmış, Irak’ta üstün İngiliz

kuvvetleriyle muharebe etmiş ve Alman İkinci Demir Salîb Nişanıyla

ödüllendirilmiştir.

7 Kasım 1916’da, 6’ncı Ordu Komutanına Dicle doğusundaki birliklerini nehrin

batısına almayı önerdiyse de Halil Paşa kabul etmemiş bu yüzden 18’nci Kolordu

ağır zayiat vermiştir.

8 Nisan 1917’de 2’nci Kolordu, 27 Aralık 1917’de de 1’nci Kafkas Kolordusu

Komutanlıklarına atanmış, Erzincan ve Erzurum’u kurtararak halkın katledilmesini

önlemiştir.

Sarıkamış, Kars ve Gümrü’nün alınmasındaki katkı ve başarıları nedeniyle 28

Temmuz 1918’de Mirlivalığa yükseltilmiş, İkinci Rütbeden Kılıçlı Mecidi ve

Osmanî Nişanları ve Altın Muharebe Liyakat Madalyası ile ödüllendirilmiştir.

Almanya, Avusturya – Macaristan da çeşitli nişan ve madalyalarıyla kendisini

onurlandırmışlardır.

Eylül 1918’de Baku ve Tebriz alınmış, hatta daha ilerilere de gidilmiştir.

Fakat 30 Ekim 1918’de Mondros Mütarekesi imzalanınca 1877-1878 hattına

çekilindi. 24 Aralık 1918’de İngilizler de Batum’u işgal ettiler.

Kâzım Karabekir Paşa, 2 Mart 1919’da 15’nci Kolordu Komutanlığına atanarak

Erzurum’a gitti. İzmir’in işgaliyle, millî hareketi hızlandırdı. 9 Haziran

1920’de de Doğu Cephesi Komutanlığı onaylandı

.

25 Temmuz 1920’de İngilizlerin boşalttığı Batum’u Gürcülerin işgal etmesini

protesto ettik. Kâzım Karabekir Paşa hazırladığı plânı uygulayarak 30 Eylül

1920’de Sarıkamış’ı, 30 Ekimde Kars’ı ele geçirdi. 31 Ekim 1920’de Ferik

(Korgeneral)’liğe yükseltildi. 7 Kasım 1920’de Gümrü’yü aldı. Ermeniler ağır

zayiata uğratılarak elde edilen silâh, cephane ve malzeme Batı Cephesine

gönderildi. Kâzım Karabekir Paşa 2/3 Aralık 1920’de imzalanan Gümrü ve 13 Ekim

1921’de imzalanan Kars Antlaşmalarında Türk Heyetine başkanlık etti.

21 Ekimi923’te Doğu Cephesi lağvedildi. Kâzım Karabekir Paşa da, 1’nci Ordu

Müfettişliğine atandı ve İstiklâl Madalyası ile ödüllendirildi.

31 Ekim 1924’te Ordu Müfettişliğinden istifa ederek Milletvekilliği görevine

devam etti ve 17 Kasım 1924’te Meclisteki muhaliflerden oluşan Terakkiperver

Cumhuriyet Fırkası (Partisi)’nin liderliğine getirildi.

Kâzım Karabekir Paşa, 1 Kasım 1927’de ordu açığında iken emekliye

ayrıldı.

1938’den sonra V ve VIII’nci dönemlerde İstanbul Milletvekili olarak Büyük

Millet Meclisinde bulunmuş, 1946-1948 yılları arasında Türkiye Büyük Millet

Meclisi Başkanlığı yapmıştır. Bu görevde iken 25 Ocak 1948’de vefat etti.

Kâzım Karabekir, Fransızca, Rusça, Bulgarca ve Almanca bilirdi. Askerî,

siyasî, tarihî ve terbiyevî kırktan fazla basılmış eseri bulunmaktadır.1

Kâzım Karabekir Paşa’nın Askerî

Nitelikleri:

Kâzım Karabekir Paşa, ciddî, çalışkan, dürüst, bilgili, cesur, kesin karar

sahibi, üstün ahlâklı bir askerdi. Gerek kurmay görevlerinde ve gerekse komuta

ettiği birliklerde astlarının güvenini kazanmış, onları sevmiş ve kendisini

sevdirmişti. Eğitime çok önem verirdi. Sorumluluktan asla yılmaz kanun ve

yönetmeliklerin kendisine tanıdığı yetkileri hiç bir etki altında kalmadan

kullanırdı.

Yaşadığı dönemde cereyan eden muharebelerin hemen tümüne katılmış, çok

tecrübeli bir komutandı. Doğu Cephesi Komutanı olarak kazandığı zaferler, Türk

ve yabancı tüm askerî otoriteler tarafından takdir edilmekte, en kritik dönemde

Mustafa Kemal Paşa’ya ve davaya bağlılığı, vefakârlığı övülmektedir.

Kâzım Karabekir Paşa, iyi yetişmiş bir asker, başarılı bir komutandı.

Kâzım Karabekir’in Katıldığı

Savaşlar:

1 Nisan 1910’daki Arnavutluk Ayaklanması ve Balkan Harbindeki görevlerine

yaşamı bölümünde değinilmişti.

BİRİNCİ DÜNYA

HARBİNDE:

Birinci Dünya Harbi, 3 Ağustos 1914’te bütün Avrupa’yı sarmış, 29 Ekim

1914’te Alman Amirali Suşon komutasındaki Türk donanmasının Karadeniz’deki harp

gemilerini batırması ve limanlarını bombardıman etmesi üzerine Ruslar, doğu

sınırlarımıza tecavüz ettiler, İngiliz Deniz Kuvvetleri de Akabe, Basra

Körfezlerine ve Çanakkale Boğazındaki hedeflere ateş açarak düşmanca durum

takındılar. 3 Kasım 1914’te Üçlü Anlaşma Devletleriyle harbe girmiş

bulunuyorduk.

Doğu Cephemizde muharebenin şiddetlenmeye başladığı günlerde, Genel Karargâh

İstihbarat Şube Müdürü Kurmay Yarbay Kâzım Karabekir 1’nci Kuvve-i Seferiye

(Tümen) Komutanlığına atanmış ve 3 Ocak 1915’te tümeniyle İstanbul’dan

ayrılmıştı.

Yarbay Kâzım Karabekir, Halep’e geldiği sırada, Sarıkamış Muharebesi

felâketle sonuçlanmış, Irak’ta Rota Muharebesi başlamıştı. 20 Ocak 1915’te Irak

ve Havalisi Genel Komutanı Yarbay Süleyman Askeri yaralanmış, yerine Kurmay

Yarbay Kâzım Karabekir gönderilmişti. Bağdat’a kadar gittiği halde Yarbay

Süleyman Askeri, görevi devretmediği gibi, Kurmay Yarbay Kâzım Karabekir’in

harekât plânı üzerindeki önerilerini de dikkate almamıştı; Kâzım Karabekir

taarruz istikametinin değiştirilmesini, ikmal teşkilâtının kurulmasını,

İngilizleri küçümsememesini, aşiretlere güvenmemesini önermiş, henüz Halep’ten

ayrılmamış olan 1’nci Kuvve-i Seferiye’nin Bağdat’a gönderilmesini de Enver

Paşa’dan istemişti.

Her iki makamca da önerileri kabul edilmeyen Kâzım Karabekir, 10 Şubat’ta

Bağdat’tan ayrılarak İstanbul’a geldi. 14’ncü Tümen Komutanlığına atanmıştı.

Yarbay Süleyman Askeri de, Şuayyibe Muharebesinde birliklerinin % 50’sini

kaybederek, intihar etti.

ÇANAKKALE

CEPHESİNDE:

Anlaşma Devletleri, 19 Şubat 1915’te Rusların yükünü hafifletmek ve onlara

yardım sağlamak amacıyla başlattıkları deniz harekâtı, 18 Mart 1915 günü

zaferimizle sonuçlanınca, Boğazları kara harekâtıyla düşürmek için 25 Nisan

1915’te Gelibolu yarımadasına çıkarma yaptılar. (Arıburnu ve Seddülbahir

bölgelerine)

Seddülbahir kıyılarına çıkan İngiliz ve Fransız birlikleri, nisan, mayıs,

haziran aylarında Kirte, temmuz ayındaki Kerevizdere muharebelerinde yıpranmış,

Türk birlikleri de ağır zayiat vermişti. Bu birliklerden Kerevizdere

bölgesindeki 4’üncü Tümeni, İstanbul’dan gelen Kurmay Yarbay Kâzım Karabekir

Komutasındaki 14’ncü Tümen değiştirdi.

Tümgeneral Fevzi (Mareşal Çakmak) komutasındaki 5’nci Kolordu kuruluşunda

muharebeye katılan 14’ncü Tümenin 42 ve 55’nci Alayları cephede, 41’nci Alayı

ihtiyatta olmak üzere tertiplenmişti. Karşısında iki tümenli Fransız kolordusu

vardı.

6 Ağustos günü başlayan Seddülbahir taarruzu, 7 Ağustos’ta şiddetlendi,

42’nci Alay bölgesine giren Fransız birlikleri, bu alayın karşı taarruzları ve

tümen birliklerinin şiddetli ateş desteği karşısında panik halinde

çekildiler.

5’nci Kolordu birlikleri, özellikle 14’ncü Tümen de ağır zayiat vermişti.

Kurmay Albay Mustafa Kemal’in yüksek sevk ve idaresindeki Anafartalar

Muharebelerini de kaybeden Anlaşma Devletleri birlikleri, 20 Aralık 1915’te

Arıburnu kesimini, 9 Ocak 1916’da da Seddülbahir kesimini tamamen tahliye

etti.2

IRAK

CEPHESİNDE:

Çok geniş yetkilerle 6’ncı Ordu Komutanlığına atanan Von Der Goltz’ün (Alman

Mareşali) Kurmay Başkanı olarak 6 Aralık 1915’te Bağdat’a gelen Kâzım Karabekir,

14 Aralık’ta Albaylığa yükseltildi ve 27 Nisan 1916’da da 18’nci Kolordu

Komutanlığına atandı. 29 Nisan 1916’da Kütülammare alındı. General Towsend ve

5’nci Tugay Komutanı tutsak edilerek Bursa’daki kampa gönderildiler.

Mareşal Von Der Goltz’ün tifüsten ölmesi üzerine 6’ncı Ordu Komutanlığına

Tümgeneral Halil (Korgeneral Kut) atanmıştı. 6’ncı Ordu, 13 ve 18’nci

Kolordulardan oluşuyordu. Kurmay Albay Ali İhsan (Tümgeneral Sabis)

komutasındaki 13’ncü Kolordu, Bağdat istikametinde ilerleyen Rusların 1’nci

Kafkas Kolordusunu Hemedan doğusuna sürmüştü. 22 Aralık 1917’de Ruslarla anlaşma

yapılınca, 13’ncü Kolordu Cebeli Hamrin kuzeyine çekildi. (İngilizlerle

çarpışarak)

Kurmay Albay Kâzım Karabekir komutasındaki 18’nci Kolordu Süveyce Horu

(bataklığı) ile Kütülammare arasındaki Dicle Nehri kuzey kıyılarını ve İmamı

Muhammet, Garraf ve Beşare köprübaşı mevzilerini savunmak üzere

tertiplenmekteydi.

Kâzım Karabekir, Ordu Komutanına bu köprübaşı mevzilerinde direnmenin

sakıncalarını belirtmiş ve buradaki birliklerin de nehrin kuzey kesimine

alınarak, kıyı değiştirecek İngiliz birliklerinin karşı taarruzlarla nehre

dökülmesini önermişse de Ordu Komutanı köprübaşı mevzilerinin savunulmasında

ısrar etmişti.

Taarruza geçen İngiliz birlikleri, önce İmamı Muhammet mevziîne üstün

kuvvetlerle yöneldi ve sahra tahkimatıyla berkitilmiş bu mevziî yoğun topçu

ateşi altına alarak erlerimizin silâhlarını kullanmasına dahi fırsat vermedi.

Muharebe alanını şehitlerimizin cesetleri doldurmuştu. Gönderilen takviyeler de

aynı şekilde eriyordu. 18’nci Kolordunun mevcudu 18.000’den 5.000’e düştü.

Bağdat, İngilizlerin eline geçti.

Mütareke hükümlerine rağmen İngilizler, kuzeydeki petrol havzasını ele

geçirerek Diyarbakır’a kadar ilerlediler. Bununla da yetinmediler; bölgedeki

aşiretleri ayaklandırarak Musul ve Kerkük bölgesinin Misak-ı Millî sınırlarımız

dışında kalmasını sağladılar. 3 6’ncı Ordu Komutanı, Albay Kâzım Karabekir’in

önerisini değerlendirseydi, sonuç değişebilirdi.

KAFKAS

CEPHESİNDE:

Kurmay Albay Kâzım Karabekir önce, Diyarbakır bölgesindeki 2’nci Kolordu, 27

Aralık 1917’de de Refahiye bölgesindeki 1’nci Kafkas Kolordu Komutanlığına

atandı. 3’ncü Ordu’nun ileri harekâtı sırasında, 13 Şubat 1918’de Erzincan’ı, 12

Mart 1918’de de Erzurum’u, Ermeni birlik ve çetelerinden temizledi (Bu illerdeki

Rus birlikleri, 18 Aralık 1917’de yapılan anlaşma gereğince ayrılmış, yerlerini

Ermeni birlik ve çetelerine bırakmışlardı). Kâzım Karabekir’in Erzurum’un

kurtarılmasında, sorumluluğu üstlenerek durumun gerektirdiği icraatı tereddütsüz

uygulamasını anmadan geçemiyeceğim.

3’ncü Ordu Komutanı Korgeneral Vehip (Kaçı) Erzurum yönünde 5 ve 9’ncu Kafkas

Tümenlerinden birer alayla taarruzî keşif yapılmasını istemişti. Kâzım

Karabekir, bir an evvel Erzurum’u ele geçirip ilerdeki harekât için oradaki

olanaklardan yararlanmak ve katliamı önlemek amacıyla, 9’ncu Kafkas Tümeni’nin

tamamını muharebeye sokarak Ermenileri püskürttü.

15 Nisan 1918’de Sarıkamış, 26 Nisan’da Kars, 15 Mayıs’ta da Gümrü

alındı.

Kâzım Karabekir 28 Temmuz 1918’de Tümgeneralliğe yükseltildi. Eylül 1918’de

birliklerimiz kuzeyde Bakü’yü, güneyde Tebriz’i ele geçirmişler, ilerlemeyi

sürdürüyorlardı.

30 Ekim 1918’de imzalanan Mondros Müterakesi hükümlerine göre, Şubat 1919’a

kadar, 1877-1878’deki sınırlarımıza çekilmek zorunda bırakıldık.4

İSTİKLÂL

HARBİNDE:

İtilâf Devletleri, Mondros Mütarekesi’ne dayanarak yurdumuzu parçalayıp

bölüşmeye ve stratejik yollara hâkim olmaya başlamışlardı. Kışkırtılan ve

desteklenen azınlıklar da, şiddet eylemlerine giriştiler. Halk üzgün ve

perişandı. Bölgesel kuruluşlar oluşuyor; fakat toparlanamıyorlardı. Padişah, taç

ve tahtını düşünüyor, hükümet işgalci devletleri gücendirmeme-ye

çalışıyordu.

Tümgeneral Kâzım Karabekir bu sırada İstanbul’a geldi. O, İstanbul’da bir şey

yapılamayacağı kanısındaydı. Mustafa Kemal de kendisine, “Erzurum’a gitmesini ve

orada halkı teşkilâtlandırmasını” önerdi. 15’nci Kolordu Komutanlığını kabul

ederek Erzurum’a gitti ve Doğu Cephesi Komutanı olarak Kars ve dolaylarını bir

kere daha kurtardı.

Ermeniler, Türk ordusunun Kuzeybatı İran’ı ve Kafkasya’yı boşaltmasını fırsat

bilmiş, Gümrü (Leninakan) Açmıyaz’ın bölgelerini, Arpaçay ile Araş Nehri

kıyılarını ve Iğdır dolaylarını işgal ederek bölgedeki Türklere insanlık dışı

davranışlarını sürdürmeye başlamışlardı.

Ermenilerin, Türkler aleyhine giriştikleri bu olaylara ve 19 Haziran 1920’den

itibaren Oltu bölgesinde başlattıkları taarruz ve işgal hareketlerine artık bir

son vermenin zamanı gelmişti. Ruslar ile başlayan ilişkileri geliştirebilmek

için de, direk sınır bağlantısı kurmak gerekliydi. 24 Eylül 1920 Bardız baskını

üzerine, 9’ncu Tümen’e, karşı taarruzlarla bu kesimdeki Ermeni mevzilerini ele

geçirmesi emredildi. Bu tümenin sağladığı başarıdan yararlanarak 29 Eylül

1920’de genel taarruza geçildi. Harekât başarıyla gelişti ve 30 Eylül sabahı

12’nci Tümen Sarıkamış’a girdi.

Harekâtın ikinci safhası Kars’ın kurtarılmasıydı. Kuvvetli tahkim edilmiş

olan bu şehre doğrudan doğruya taarruz ağır zayiata neden olacağından, doğu ve

kuzeydoğudan kuşatılarak 30 Ekim 1920’de Kars da ele geçirildi. Ermenilerin

Savunma Bakanları ile Genelkurmay Başkanları da esirler arasındaydı.

Bu muharebede iğtinam edilen ikmal maddelerinin büyük kısmı Batı Cephesine

gönderilmiş, Kâzım Karabekir de bu başarıları nedeniyle Korgeneralliğe

yükseltilmişti.

3 Kasım 1920’de Gümrü istikametinde harekâta devam edildi.6 Kasım akşamı

Ermeniler Gümrü batı sırtlarına atıldılar ve barış yapılmasını önerdiler. 7

Kasımda Gümrü ele geçirildi; 2/3 Aralık 1920’de Gümrü Antlaşması yapıldı.

Antlaşmanın imzasından bir gün sonra Ermeni Taşnak Hükümeti Kızıl Ordu

tarafından ortadan kaldırıldığından, Gümrü Antlaşması onaylanamadı. 13 Ekim

ig2i’de Ermenistan, Gürcistan, Azerbaycan Sosyalist Cumhuriyetleri ve Rusya ile

Kars Antlaşması imzalanarak yürürlüğe girdi.

Doğu Cephesi birliklerinden 3’ncü Kafkas Tümeni—11’nci Piyade Alayı hariç—

Batı Cephesine gönderildi. Sakarya Meydan Muharebesi ve Büyük Taarruza

katıldı.

12’nci Tümen de 4 Ağustos 1921 ‘den itibaren şevke başlandı. 28 Eylül 1921’de

Ankara’ya varan bu tümen de Büyük Taarruza katıldı.

II’nci Kafkas Tümeni, Mayıs 1922’de Koçhisar dolaylarında lağvedilerek 21’nci

Tümenin teşkili ve bazı birliklerin takviyesi sağlandı.3

Görüldüğü gibi, Korgeneral Kâzım Karabekir, Batı Cephesine sadece yiyecek,

giyecek, silâh ve cephane göndermekle kalmamış, üç tümeniyle bu cepheyi takviye

ederek harbin kazanılmasına da katkıda bulunmuştur.

Edirne ve İstanbul Milletvekilliği yapan Kâzım Karabekir 25 Ocak 1948’de,

TBMM Başkanı iken vefat etmiştir. O tarihte Cumhurbaşkanı bulunan İsmet İnönü,

28 Ocak 1948’deki konuşmasını şöyle bitiriyordu:

“… Tarihimiz, Kâzım Karabekir’in Millî Mücadeledeki hizmetlerini vefalı

sayfalarında her zaman övünçle anacaktır. Birinci Dünya Harbi’nin felâketli

sonucunun ilk gününden başlayarak, hiç sarsılmayan bir inançla meydana atılmış

olan pek değerli vatanseverlerinden biriydi. Kâzım Karabekir’in zaferleri, batı

ve güney sınırlarımızda ve içeride türlü şekildeki saltanat hareketlerine karşı

gerçekten bunalmış olduğumuz bir zamanda yetişmiştir. Ordu ve memlekette oluşan

şevk ve sevinç bütün kurtuluş hareketlerimize yepyeni bir atılışın bütün umut

ufuklarını açmış, yüreklerimiz taşkın bir minnetin heyecanı ile dolmuştu.

Karabekir adı, İstiklâl Harbi’nin büyük abidelerinden biri olarak milletin

takdirinde ebedî bir şeref yeri tutacaktır. Büyük komutan, devlet ve siyaset

adamı ve kemal sahibi bir insan olarak yüksek nitelikleri ve hiç bir güçlük

karşısında yılmayan iman ve iradesi, hafızamızda canlı olarak yaşayacaktır.”

Kâzım Karabekir’in Hava Şehitliği’nde bulunan aziz naaşı Devlet Mezarlığı’na

nakledilecektir. Ruhu şad olsun.

1 Türk İstiklâl Harbine Katılan Tümen ve Daha Üst Kademelerdeki Komutanların

Biyografileri, Gnkur. Harp Tarihi Başkanlığı Yayını, Ankara, Gnkur. Basımevi,

1972, s. 161, 163. Türk Harp Tarihi Derslerinde Adı Geçen Komutanlar, Harp

Akademileri Komutanlığı, İstanbul, Harp Akademileri Basımevi, 1983, s. 397 –

404. Karabekir, Kâzım; Yayınlanmış eserleri. Şahsî dosyası.

2 Birinci Dünya Harbinde Türk Harbi, C.V, 3’ncü Kitap,Çanakkale Cephesi

Harekâtı, Gnkur. ATASE Bşk. lığı, Ankara, Gnkur. Basımevi, 1980, s. 223,

419.

3 Birinci Dünya Harbinde Türk Harbi; Irak Cephesi Harekâtı, Gnkur. ATASE

Bşk.lığı (Müsvedde halinde).

4 BELEN, Fahri, Birinci Cihan Harbinde Türk Harbi, C. IV, V, 1917-1918

Harekâtları, Gnkur. Basımevi, Ankara 1967. Çakmak, Fevzi; Büyük Harpte Şark

Cephesi Harekâtları, Harp Akademileri Matbaası, İstanbul (Konferanslar

halinde).

5 Türk İstiklâl Harbi, C. III, Doğu Cephesi (1919-1921) Gnkur. Harp Tarihi

Dairesi Başkanlığı, Gnkur. Basımevi, Ankara, 1965.

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Friday, January 27, 2017

Tuniisia's Fragile Democracy

Peripheral Vision: How Europe Can Help Preserve Tunisia´s Fragile Democracy

25 Jan 2017

By Hamza Meddeb for European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in January 2017.

Summary

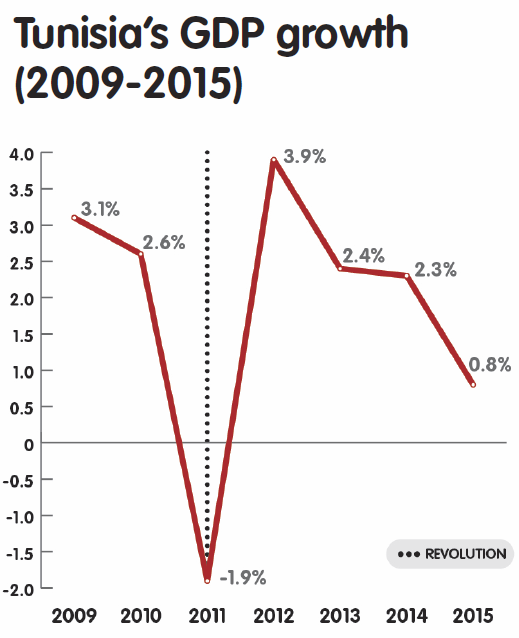

- Six years since the revolution, the success of democracy in Tunisia depends on those parts of the country where the popular uprising began: its ‘periphery’, whose regions lag far behind the country’s economically more developed coast.

- Tunisia’s periphery regions suffer from weak economic growth and high levels of poverty and unemployment – a legacy of decades of underinvestment.

- Regional conflict, terrorism and organised crime have led the government to crack down on security threats in the periphery regions. This has disrupted the informal and illegal economic networks on which much of the population relies and caused it to lose faith in the government.

- Tunisia has enjoyed extensive support from international partners since 2011 – money is not the problem. Instead, the country must strengthen its regional governance and address fragmentation at the heart of government.

- Europeans can radically alter the terms of debate by offering Tunisia membership of the European Economic Area, galvanising change in support of its journey towards democracy and stability.

Among the countries involved in the Arab uprisings, Tunisia stands out. Its transition to democracy has experienced setbacks, but is still in train. However, for the future success and stability of Tunisia – and Europe’s southern neighbourhood – it is important to understand one simple fact, something approaching a twist of fate: Tunisia’s future lies in the very place where the 2010-2011 popular uprising first erupted. Its inland ‘periphery regions’ are home to Sidi Bouzid, the city where Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in 2011, sparking the chain of events that led to the overthrow of the Ben Ali regime. Away from the economically developed coast familiar to Europeans, Tunisia’s periphery plays host to many of the afflictions that, if left unchecked, could bring to an end Tunisia’s lonely battle to establish a fully fledged democracy.

Six years on from the revolution, Tunisia’s long-neglected hinterland continues to suffer from a rampant informal economy, high unemployment, corruption and an underdeveloped private sector. Recent efforts made by the central government to improve security in the periphery, especially along the border with Libya and Algeria, have resulted in increased securitisation in these areas and upset the cross-border economy that the local population has long relied on for its livelihood. As a result, the legitimacy of post- 2011 democratic governments has withered in the eyes of the people. Meanwhile, long-standing smuggling, jihadi and tribal networks have increasingly overlapped and combined to increase instability and hinder progress towards greater socioeconomic development. The government has in turn done itself no favours thanks to its fragmented central structures, its failure to take advantage of the significant international support and investment made in Tunisia since the revolution, and its possible participation in corruption reaching from the central decision-making level down to regional and local levels.

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution represents an important achievement that seeks to build a pluralistic political system as well as an inclusive and resilient society. It recognises the problem of regional disparities and enshrines the principle of “positive discrimination” to favour disadvantaged regions – the question that sits at the heart of this paper. But how this is to be done has thus far been left ill-defined. Neither the Islamist-led coalition governments between 2011 and 2013, nor the technocrats’ government of 2014, nor the post-2014 coalition government led by Habib Essid were able to resolve these structural problems. A new coalition government led by Youssef Chahed is currently in charge of putting in place a much-needed reform agenda.

Tunisia risks seeing its periphery regions become ‘areas of limited statehood’ – areas where government authorities and institutions become too weak to enforce central decisions and where non-state actors could eventually prevail over the authority of the central government. Moreover, the country risks losing its most precious asset: its youth, which is confronted with fewer and fewer options: emigration, contraband or protest. Finally, failure to kickstart development in the peripheries will only further foster the conditions in which radical groups thrive, so proficient are they at harnessing social anger.

Europe, in turn, risks losing one of the few islands of relative stability in the Middle East and North Africa region. It is important that Europeans grasp the economic, political and social dynamics at play in the country’s peripheries and these dynamics’ relationship with the political centre. Europeans should reflect on the ways in which they can better use existing policy tools to support much-needed integration efforts. The road ahead is all the more gruelling thanks to strong vested interests that will attempt to defend the current, deficient, economic policy. And yet the endeavour remains worthwhile, because strengthening Tunisia’s national resilience is key to diminishing the risks of conflict spillover, ensuring a stable neighbourhood for Europe, and building a genuine Arab democracy.

Tunisia’s regional asymmetries

Tunisia’s interior and border regions were the hotbed of the uprising that took place in 2010-2011. They have been a major source of political instability ever since, acting as a stark reminder that regional inequality can be a potent source of nationwide tension. Conscious decisions made by successive governments since Tunisian independence have resulted in a substantial development gap between the coast and the periphery. Post-revolution governments have struggled to address these disparities, and have failed to counter ongoing corruption and meet the demands of the country’s youth population.

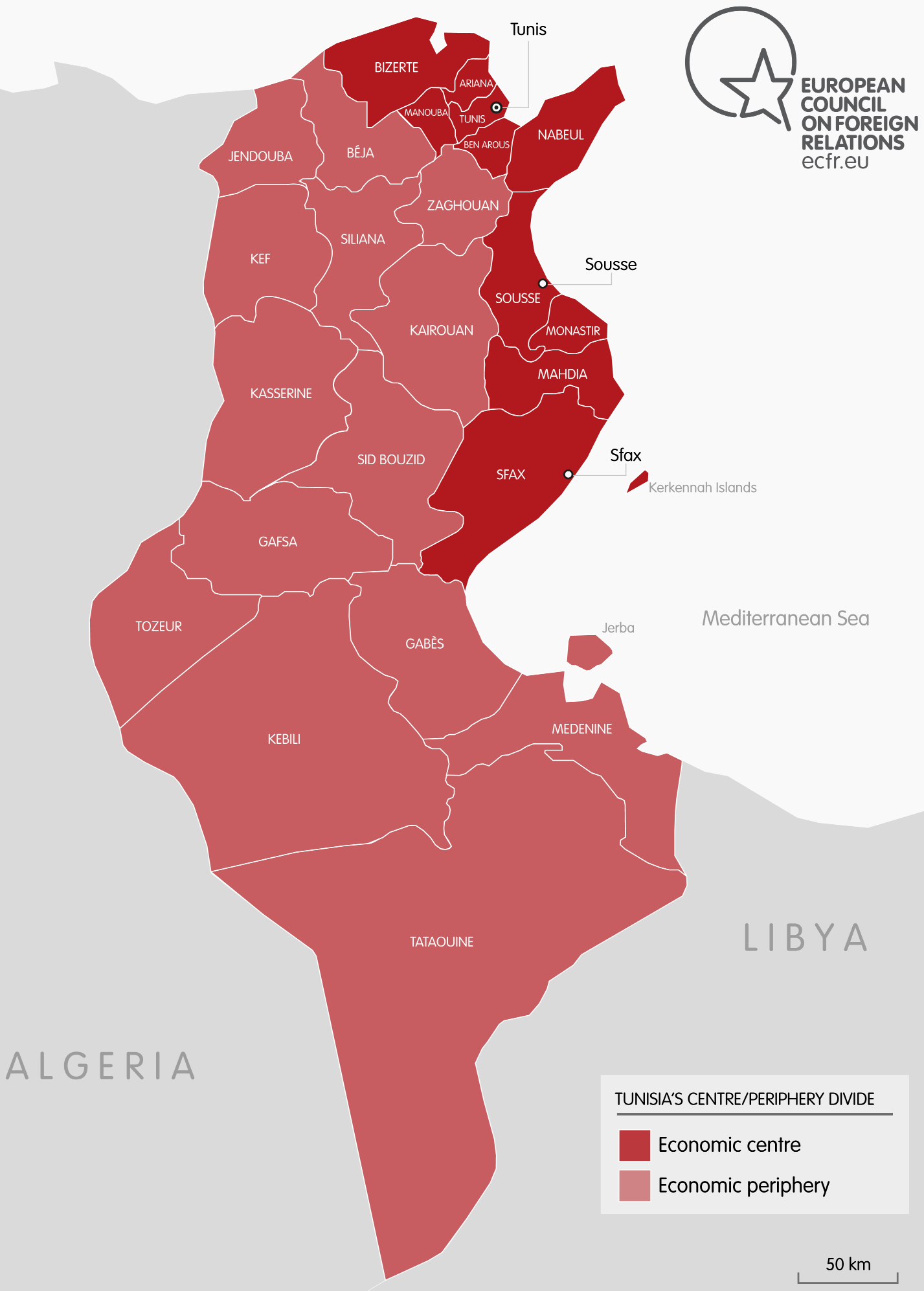

The legacy of history

That the revolution started in the peripheries is no accident. Since Tunisia gained independence in 1956, coastal regions have consistently been promoted at the expense of the interior and border regions. This pattern of marginalisation only worsened under Ben Ali, who took power in 1987 and under whom two-thirds of public investment came to be allocated to the coastal regions. Tunisia developed as an export-orientated economy focused on tourism and low-cost outsourcing, with the bulk of infrastructure investment targeted on these regions. Investment incentives were orientated to the need to maintain competitiveness and access to international markets by tolerating low wages at the expense of agriculture and of rural areas. This deficit in infrastructure and private investment progressively reduced Tunisia’s peripheries to reservoirs of cheap labour, agrarian products and raw materials for the more developed industries and service sectors operating in the coastal regions. Approximately 56 percent of the population and 92 percent of all industrial firms are located within an hour’s drive of Tunisia’s three largest cities: Tunis, Sfax and Sousse. Economic activity in these three coastal cities accounts for 85 percent of Tunisia’s GDP. On the eve of the fall of Ben Ali, poverty was estimated at 42 percent in the Centre West and 36 percent in the North West, whereas it was at the much lower rate of 11 percent in Tunis and the Centre East.

Under Ben Ali, there was no strategy of inclusive development to redress these regional imbalances. In fact, the gap between the coast and peripheries was less the result of neglect than a consequence of deliberate political decisions. The low-cost and pragmatic mode of governing adopted by the regime was part of a bigger strategy designed to cope with fiscal and budgetary constraints. This included the deployment of patronage and intermediation mechanisms involving tribal and local elites through the Tunisian General Labour Union and the former ruling party, the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique. Clientelist networks and the security forces controlled the job market, social benefits, and the informal economy through protection from law enforcement. For instance, jobs at the Gafsa Phosphates Company (CPG) would be distributed among local patrons and regional administrations according to a quota system. In turn, the latter would redistribute these jobs among their clients on a tribal or partisan basis, or even sell them to the highest bidder. These clientelist resource distribution systems maintained a minimal and fragile stability over two decades in the Tunisian periphery while fuelling the fragmentation of local society and helping consolidate tribal identities.

Six years on from the revolution, Tunisia’s long-neglected hinterland continues to suffer from a rampant informal economy, high unemployment, corruption and an underdeveloped private sector. Recent efforts made by the central government to improve security in the periphery, especially along the border with Libya and Algeria, have resulted in increased securitisation in these areas and upset the cross-border economy that the local population has long relied on for its livelihood. As a result, the legitimacy of post- 2011 democratic governments has withered in the eyes of the people. Meanwhile, long-standing smuggling, jihadi and tribal networks have increasingly overlapped and combined to increase instability and hinder progress towards greater socioeconomic development. The government has in turn done itself no favours thanks to its fragmented central structures, its failure to take advantage of the significant international support and investment made in Tunisia since the revolution, and its possible participation in corruption reaching from the central decision-making level down to regional and local levels.

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution represents an important achievement that seeks to build a pluralistic political system as well as an inclusive and resilient society. It recognises the problem of regional disparities and enshrines the principle of “positive discrimination” to favour disadvantaged regions – the question that sits at the heart of this paper. But how this is to be done has thus far been left ill-defined. Neither the Islamist-led coalition governments between 2011 and 2013, nor the technocrats’ government of 2014, nor the post-2014 coalition government led by Habib Essid were able to resolve these structural problems. A new coalition government led by Youssef Chahed is currently in charge of putting in place a much-needed reform agenda.

Tunisia risks seeing its periphery regions become ‘areas of limited statehood’ – areas where government authorities and institutions become too weak to enforce central decisions and where non-state actors could eventually prevail over the authority of the central government. Moreover, the country risks losing its most precious asset: its youth, which is confronted with fewer and fewer options: emigration, contraband or protest. Finally, failure to kickstart development in the peripheries will only further foster the conditions in which radical groups thrive, so proficient are they at harnessing social anger.

Europe, in turn, risks losing one of the few islands of relative stability in the Middle East and North Africa region. It is important that Europeans grasp the economic, political and social dynamics at play in the country’s peripheries and these dynamics’ relationship with the political centre. Europeans should reflect on the ways in which they can better use existing policy tools to support much-needed integration efforts. The road ahead is all the more gruelling thanks to strong vested interests that will attempt to defend the current, deficient, economic policy. And yet the endeavour remains worthwhile, because strengthening Tunisia’s national resilience is key to diminishing the risks of conflict spillover, ensuring a stable neighbourhood for Europe, and building a genuine Arab democracy.

Tunisia’s regional asymmetries

Tunisia’s interior and border regions were the hotbed of the uprising that took place in 2010-2011. They have been a major source of political instability ever since, acting as a stark reminder that regional inequality can be a potent source of nationwide tension. Conscious decisions made by successive governments since Tunisian independence have resulted in a substantial development gap between the coast and the periphery. Post-revolution governments have struggled to address these disparities, and have failed to counter ongoing corruption and meet the demands of the country’s youth population.

The legacy of history

That the revolution started in the peripheries is no accident. Since Tunisia gained independence in 1956, coastal regions have consistently been promoted at the expense of the interior and border regions. This pattern of marginalisation only worsened under Ben Ali, who took power in 1987 and under whom two-thirds of public investment came to be allocated to the coastal regions. Tunisia developed as an export-orientated economy focused on tourism and low-cost outsourcing, with the bulk of infrastructure investment targeted on these regions. Investment incentives were orientated to the need to maintain competitiveness and access to international markets by tolerating low wages at the expense of agriculture and of rural areas. This deficit in infrastructure and private investment progressively reduced Tunisia’s peripheries to reservoirs of cheap labour, agrarian products and raw materials for the more developed industries and service sectors operating in the coastal regions. Approximately 56 percent of the population and 92 percent of all industrial firms are located within an hour’s drive of Tunisia’s three largest cities: Tunis, Sfax and Sousse. Economic activity in these three coastal cities accounts for 85 percent of Tunisia’s GDP. On the eve of the fall of Ben Ali, poverty was estimated at 42 percent in the Centre West and 36 percent in the North West, whereas it was at the much lower rate of 11 percent in Tunis and the Centre East.

Under Ben Ali, there was no strategy of inclusive development to redress these regional imbalances. In fact, the gap between the coast and peripheries was less the result of neglect than a consequence of deliberate political decisions. The low-cost and pragmatic mode of governing adopted by the regime was part of a bigger strategy designed to cope with fiscal and budgetary constraints. This included the deployment of patronage and intermediation mechanisms involving tribal and local elites through the Tunisian General Labour Union and the former ruling party, the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique. Clientelist networks and the security forces controlled the job market, social benefits, and the informal economy through protection from law enforcement. For instance, jobs at the Gafsa Phosphates Company (CPG) would be distributed among local patrons and regional administrations according to a quota system. In turn, the latter would redistribute these jobs among their clients on a tribal or partisan basis, or even sell them to the highest bidder. These clientelist resource distribution systems maintained a minimal and fragile stability over two decades in the Tunisian periphery while fuelling the fragmentation of local society and helping consolidate tribal identities.

After the revolution

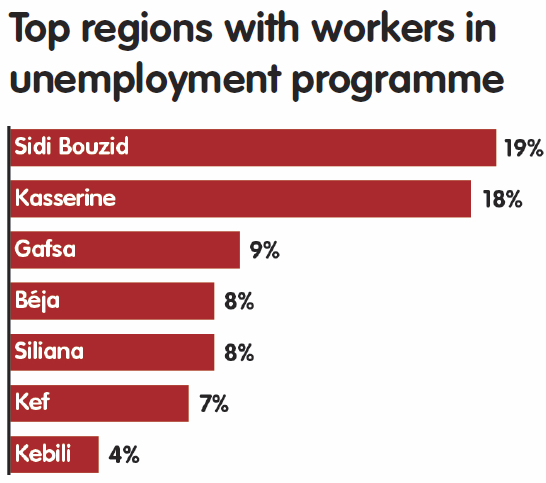

After the fall of the Ben Ali regime, many residents in the periphery regions hoped the central state would recognise its own shortcomings and would finally reverse the trajectory of marginalisation, deliver better governance, meet social and economic needs, and tackle inequality. However, the solution of successive post-2011 governments was to create a large number of public sector jobs and to roll out temporary mass employment programmes such as ‘les chantiers’. In this way, for example, CPG’s labour force grew from 5,000 in 2010 to 27,000 in 2015 and the number of workers hired through the programme leapt from 62,875 in 2010 to 125,000 in 2011. With approximately 100,000 workers in 2015, the ‘les chantiers’ is a crucial instrument in addressing the lack of economic opportunities and to manage social anger in the periphery. Centres of the popular uprising, the regions of Sidi Bouzid and Kasserine represent a total of 37 percent of people hired through it. In total, 77 percent of the workers hired through this programme are from the periphery regions.

Far from supplying sustainable economic opportunities, employment schemes offering temporary jobs contribute to ongoing patterns of subordination and marginalisation. The anaemic nature of the private sector in Tunisia has proved a great hindrance, exacerbating the economic marginality of the periphery regions’ inhabitants and reducing the new ruling elites’ options. Nonetheless, ceasing these employment schemes would likely provoke social unrest in these regions. Because government jobs are often the only hope for job security, competition rages between networks, tribes and political parties to secure these positions.

Meanwhile, 85 percent of the enterprises that provide 92 percent of private sector jobs are clustered in the coast regions: 44 percent are to be found in the Great Tunis area alone. Enterprises operating inland provide only 8 percent of private sector jobs. Foreign companies in the interior regions account for less than 13 percent of the total of foreign firms established in Tunisia. Together, public investment choices and the weakness of the private sector explain the high unemployment in the peripheries: as high as 27 percent in Tataouine, 26 percent in Jendouba, and 22 percent in Kasserine. The average national unemployment rate in 2015 stood at 15 percent. These economic inequalities have exerted a negative social impact in terms of poverty rates, which follow a similar centre-periphery divide, and in some places, particularly the Centre West, are double the national average.

In addition, corruption remains a major challenge. Since 2011, the issue has gone largely unaddressed at all levels of government – local, regional and national. Bribes remain necessary in order to get a licence to start a small business, obtain a job in an employment programme, or receive social assistance from the state. Moreover, according to some entrepreneurs, the corruption currently hindering the much-needed investment in the interior regions can be traced back to the central decision-making level. State officials, bankers and business owners participate in networks that bind them together and facilitate corrupt practices, including even securing the foreclosure of competitors’ businesses. These networks exercise control over state resources, especially bank credit and licences, and are influential within the public administration. Corruption is also a widespread feature of the state administrations at the local and regional level. Municipal and regional elections have been postponed several times, and these delays are increasing the sense of impunity among local and regional bureaucrats, which in turn creates a sort of systemic and decentralised corruption.

Finally, the post-2011 governments have so far failed to meet the demands of the increasingly frustrated youth in parts of Tunisia where socioeconomic protests remain a persistent problem. In January 2016, a wave of social unrest and violent demonstrations began in Kasserine and spread through 16 other governorates. The protests sought to condemn unemployment and denounce the corruption plaguing the regional administration. It eventually destabilised the government of the then prime minister Habib Essid. In September 2016, in the mining region of Gafsa, and the Jendouba governorate adjacent to the Algerian border, one protest against economic marginalisation and local corruption lasted several weeks. In response, the proposed short-term approaches to managing the crisis of the peripheries appear only to have increased the fault lines both within local society and between the regions, and to have fed a sense of dispossession among young people.

Sources of destabilisation

Since 2011 the government has adopted a security-heavy approach in the peripheries in an attempt to contain threats from jihadi groups and to crack down on smuggling. But security forces have themselves been drawn in to illegal activity and local populations feel let down by the government’s emphasis on security over development. A thoroughgoing rethink is needed about the connections between security and the economy in order to advance the socioeconomic situation in the periphery regions.

New conflict dynamics on old fault lines

Since 2011, the turbulent regional environment has aggravated the economic and security situation for the local population in the peripheries. Chaos in Libya, persistent pockets of terrorism in Algeria, and terrorist groups affiliated with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and the Islamic State group (ISIS) have exploited the Tunisia-Algeria-Libya triangle to traffic weapons and jihadis. This has led the Tunisian government to adopt a heavy security-centred approach in the peripheries, the impact of which has been negative, causing the central state to lose rather than gain legitimacy. In fact, the spillover from the Libyan conflict is less of a threat to Tunisia than a reactive, security-centred approach that ensures a semblance of stability while feeding disenfranchisement.

There is a complex relationship between jihad and contraband which is important to understand in this context. It is a legacy of both the dictatorship era and of the ways in which these areas have been governed since 2011. It is also a consequence of the internal fractures inside the communities living in the borderlands.

After the fall of the Ben Ali regime, many residents in the periphery regions hoped the central state would recognise its own shortcomings and would finally reverse the trajectory of marginalisation, deliver better governance, meet social and economic needs, and tackle inequality. However, the solution of successive post-2011 governments was to create a large number of public sector jobs and to roll out temporary mass employment programmes such as ‘les chantiers’. In this way, for example, CPG’s labour force grew from 5,000 in 2010 to 27,000 in 2015 and the number of workers hired through the programme leapt from 62,875 in 2010 to 125,000 in 2011. With approximately 100,000 workers in 2015, the ‘les chantiers’ is a crucial instrument in addressing the lack of economic opportunities and to manage social anger in the periphery. Centres of the popular uprising, the regions of Sidi Bouzid and Kasserine represent a total of 37 percent of people hired through it. In total, 77 percent of the workers hired through this programme are from the periphery regions.

Far from supplying sustainable economic opportunities, employment schemes offering temporary jobs contribute to ongoing patterns of subordination and marginalisation. The anaemic nature of the private sector in Tunisia has proved a great hindrance, exacerbating the economic marginality of the periphery regions’ inhabitants and reducing the new ruling elites’ options. Nonetheless, ceasing these employment schemes would likely provoke social unrest in these regions. Because government jobs are often the only hope for job security, competition rages between networks, tribes and political parties to secure these positions.

Meanwhile, 85 percent of the enterprises that provide 92 percent of private sector jobs are clustered in the coast regions: 44 percent are to be found in the Great Tunis area alone. Enterprises operating inland provide only 8 percent of private sector jobs. Foreign companies in the interior regions account for less than 13 percent of the total of foreign firms established in Tunisia. Together, public investment choices and the weakness of the private sector explain the high unemployment in the peripheries: as high as 27 percent in Tataouine, 26 percent in Jendouba, and 22 percent in Kasserine. The average national unemployment rate in 2015 stood at 15 percent. These economic inequalities have exerted a negative social impact in terms of poverty rates, which follow a similar centre-periphery divide, and in some places, particularly the Centre West, are double the national average.

In addition, corruption remains a major challenge. Since 2011, the issue has gone largely unaddressed at all levels of government – local, regional and national. Bribes remain necessary in order to get a licence to start a small business, obtain a job in an employment programme, or receive social assistance from the state. Moreover, according to some entrepreneurs, the corruption currently hindering the much-needed investment in the interior regions can be traced back to the central decision-making level. State officials, bankers and business owners participate in networks that bind them together and facilitate corrupt practices, including even securing the foreclosure of competitors’ businesses. These networks exercise control over state resources, especially bank credit and licences, and are influential within the public administration. Corruption is also a widespread feature of the state administrations at the local and regional level. Municipal and regional elections have been postponed several times, and these delays are increasing the sense of impunity among local and regional bureaucrats, which in turn creates a sort of systemic and decentralised corruption.

Finally, the post-2011 governments have so far failed to meet the demands of the increasingly frustrated youth in parts of Tunisia where socioeconomic protests remain a persistent problem. In January 2016, a wave of social unrest and violent demonstrations began in Kasserine and spread through 16 other governorates. The protests sought to condemn unemployment and denounce the corruption plaguing the regional administration. It eventually destabilised the government of the then prime minister Habib Essid. In September 2016, in the mining region of Gafsa, and the Jendouba governorate adjacent to the Algerian border, one protest against economic marginalisation and local corruption lasted several weeks. In response, the proposed short-term approaches to managing the crisis of the peripheries appear only to have increased the fault lines both within local society and between the regions, and to have fed a sense of dispossession among young people.

Sources of destabilisation

Since 2011 the government has adopted a security-heavy approach in the peripheries in an attempt to contain threats from jihadi groups and to crack down on smuggling. But security forces have themselves been drawn in to illegal activity and local populations feel let down by the government’s emphasis on security over development. A thoroughgoing rethink is needed about the connections between security and the economy in order to advance the socioeconomic situation in the periphery regions.

New conflict dynamics on old fault lines

Since 2011, the turbulent regional environment has aggravated the economic and security situation for the local population in the peripheries. Chaos in Libya, persistent pockets of terrorism in Algeria, and terrorist groups affiliated with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and the Islamic State group (ISIS) have exploited the Tunisia-Algeria-Libya triangle to traffic weapons and jihadis. This has led the Tunisian government to adopt a heavy security-centred approach in the peripheries, the impact of which has been negative, causing the central state to lose rather than gain legitimacy. In fact, the spillover from the Libyan conflict is less of a threat to Tunisia than a reactive, security-centred approach that ensures a semblance of stability while feeding disenfranchisement.

There is a complex relationship between jihad and contraband which is important to understand in this context. It is a legacy of both the dictatorship era and of the ways in which these areas have been governed since 2011. It is also a consequence of the internal fractures inside the communities living in the borderlands.

Before the revolution, both the Ben Ali and the Gaddafi regimes allowed illicit practices to take place in order to help them control the border regions. On the Tunisian side, participation in the border economy used to be a prerogative of both the clientele of the hegemonic party and the various protégés of the security services: the police, the National Guard and the customs services. On the Libyan side, the Gaddafi regime used the border resources to consolidate its power through a politics of clientelism and co-optation of tribes. Only loyal tribes were permitted to participate in this border economy. An implicit arrangement was established between regimes on the one hand and loyal tribal and smuggling networks on the other, preventing the latter from getting involved in the trafficking of weapons, drugs and jihadis in exchange for turning a blind eye to other forms of contraband.

The fall of Ben Ali and Gaddafi put an end to the arrangements that once regulated this activity, and opened up the game to new players: organised crime that sought to turn Tunisia into a staging-post between Algeria and Libya; jihadi groups looking to secure the crossing of fighters and arms between Tunisia, Algeria and Libya; and ambitious smugglers who took more risks and challenged the previously co-opted smugglers through taking advantage of the security vacuum in the border regions from 2011 onwards.

In addition to this, since 2013 attacks on the Tunisian army and security services in the border regions have shifted the debate about periphery regions from a focus on their development to one around security. This has resulted in a crackdown on the smuggling networks and cross-border trade which had been essential economic resources for the population of these regions. Since August 2013, a military-enforced buffer zone has also been in place along Tunisia’s borders. In parallel, the Algerian authorities dug a trench along the border, swiftly followed by the Tunisian government, which, in the aftermath of the terrorist attack in Bardo in February 2015, dug its own trench along the Tunisia-Libya border.

The fall of Ben Ali and Gaddafi put an end to the arrangements that once regulated this activity, and opened up the game to new players: organised crime that sought to turn Tunisia into a staging-post between Algeria and Libya; jihadi groups looking to secure the crossing of fighters and arms between Tunisia, Algeria and Libya; and ambitious smugglers who took more risks and challenged the previously co-opted smugglers through taking advantage of the security vacuum in the border regions from 2011 onwards.

In addition to this, since 2013 attacks on the Tunisian army and security services in the border regions have shifted the debate about periphery regions from a focus on their development to one around security. This has resulted in a crackdown on the smuggling networks and cross-border trade which had been essential economic resources for the population of these regions. Since August 2013, a military-enforced buffer zone has also been in place along Tunisia’s borders. In parallel, the Algerian authorities dug a trench along the border, swiftly followed by the Tunisian government, which, in the aftermath of the terrorist attack in Bardo in February 2015, dug its own trench along the Tunisia-Libya border.

In response to these multifaceted security threats, the securitisation of the borders has impacted on the peripheries’ economy and society in many ways. First, it has led to uneasy relations between the army and the security services on the one hand and the local population on the other. As local populations depend on the border economy for their living, restrictions made against cross-border trade have resulted in periodic conflict with the security services and the military.

Simultaneously, state authorities are concerned about the risk of social protest if they repress smugglers. The army has succeeded in maintaining – relatively speaking – its credibility, focusing mainly on its task of border policing (in spite of cases of soldiers’ involvement in corruption). But the interior security forces enjoy much less trust than the army does, having become “entrepreneurs of insecurity” as they extended their role beyond law enforcement to deal with social protest through negotiating bribes and selling protection. This has negatively impacted on the legitimacy of the security forces, as smugglers and traders perceived it as a way to reinvent the old arrangements through the co-optation of a happy few and the exclusion of others.

Second, the outbreak of armed conflict in neighbouring Libya in 2014 generated new uncertainty in Tunisia’s periphery regions, as competition grew between smuggling networks looking for protection in Libya. Indeed, cities in the west of Libya have always played a major “city-entrepot” role for the border economy, connecting southern Tunisian cities to the global illicit economy and ensuring supply to the Tunisian market. The border economy exerts a magnetic pull on militias attracted by the prospect of controlling and benefiting from illicit flows: approximately 15 Libyan militias are positioning along the border with Tunisia. This greatly complicates Tunisian authorities’ efforts to coordinate with their Libyan counterparts on border security.

Finally, the situation was complicated further in 2014 when jihadi groups affiliated to ISIS sought to replicate what al- Qaeda did at the Tunisia-Algeria border and establish a foothold in the Libyan city of Sabratha. The jihadi group tried to attract Tunisian jihadis who sought to flee the country, especially after the crackdown on Ansar al-Sharia, a Tunisian Salafi jihadi group, labelled a terrorist organisation by the Ennahda-led government in August 2013. These jihadi groups affiliated to ISIS tried to find an anchor in the Tunisia-Libya borderland through taking advantage of the rivalry between tribes and smuggling networks in a context of economic hardship. A review of the 26 assailants from Ben Guerdane who tried to capture this border town on 7 March 2016 revealed an overrepresentation of youth originating from the R’baya’ tribe. Historically dominated by the powerful tribe of Twazine which is in control of the cross-border trade around Ben Guerdane, the marginalisation of the R’baya’ was exacerbated by an unresolved and a long-lasting conflict over land ownership. R’baya’ smugglers, traffickers and individuals ousted from the border economy following heavy-handed security measures found in jihad a narrative that allows them to resist the state and to pursue these old tribal rivalries.

Security in the peripheries is therefore directly threatened by the exacerbation of pre-existing fault lines that feed on the dynamics of the jihadisation of local conflicts, in a context of a weak central state, economic hardship, and an emerging violence-shaped economic order.

Solving the security-economy conundrum

The tightening of controls at the Algerian and Libyan borders has resulted in the exclusion of many operators from the border economy. According to a survey by International Alert, 80 percent of the respondents living in Ben Guerdane and Dhehiba, near the Libyan border, believe that being able to cross the border is now linked to corruption more than ever. A World Bank report on the informal economy in the Tunisian peripheries highlighted the risks of increasing securitisation since 2013, noting that in the absence of concrete measures to address the economic and regulatory differences in terms of tariffs, tax levels and subsidies on either side of the border, tighter controls would increase corruption among state agents over time, and eventually undermine government control.

At the time of the popular uprisings, a number of joint projects were in train that would have helped regulate and legalise cross-border trade. But a planned free trade zone between Ben Guerdane and the border crossing of Ras Jedir, as well as the convertibility of national currencies, have never materialised. The securitisation of the borders and particularly the frequent closure of the border crossings at the Tunisia-Libya border has resulted in the suspension of cross-border trade and negatively impacted on the social and economic conditions in the periphery. Informal trade represents an important part of bilateral trade with neighbouring Libya and Algeria, accounting for more than half of official trade with Libya and for more than the total official trade with Algeria. Informal trade is one of the most important activities in the border regions. For example, a large part of the fuel consumed in Tunisia is imported from Algeria and Libya. In the governorate of Medenine, 20 percent of the working-age population works in the informal trade, approximately 83 percent of which are from Ben Guerdane.

The importance of the informal economy has increased since 2011, given the diminution of economic opportunities and the end of migration to Libya. Since the fall of Gaddafi and the deterioration of the security situation, 40,000 Tunisian workers have left Libya. For more than four decades Libya was a major destination for Tunisian seasonal workers from the periphery regions who helped meet the demand for labour in their oil-producing neighbour. The loss of these incomes has increased poverty and dissatisfaction among large swathes of the population: 10,000-15,000 families have received no income since 2011 because of the crisis in Libya.

The securitisation of cross-border trade has reinforced the prevalent perception that protest and migration are two of the dwindling options left to disenfranchised youth. In November 2016, a general strike was organised under the banner of ‘Let Ben Guerdane survive’. This protest lasted several months and received the support of neighbouring border towns. The lack of economic development leads to increased emigration, often illegal, as sadly exemplified by one of the many tragic boat capsizings that killed 12 young people from Ben Guerdane off the Libyan coast in July 2016. Meanwhile, negotiations are taking place between a Tunisian civil society delegation and the representatives of Libyan border towns in order to reach an agreement on reopening the border crossing of Ras Jedir. This follows a series of protests throughout 2016 in Ben Guerdane against the interruption of cross-border trade as well as the killing of several smugglers by the military.

The security-centred approach to ensuring stability is not a durable solution. Inhabitants of the peripheries have come to conclude that the central state views these regions as mere ‘buffer zones’ and their inhabitants as second-class citizens. They consider that calls for security are used to justify the security forces’ heavy-handedness and that they stigmatise the peripheries as hotbeds of jihadism. Many of those who feel alienated turn to Libya and Algeria for subsistence, rather than their own country of Tunisia. The experience of one young smuggler who was cut out of the border economy captures the bind many people find themselves in: “I went to the capital, Tunis, to look for a job. There, a policeman asked for my documentation. He took my ID card and told me: ‘You are from Kasserine. What are you doing here?’ I replied: ‘Do I need a visa to come to Tunis?’ It is as if we are living in two different countries.”

Reforming regional governance

The failure of the post-2011 governments to successfully implement projects and improve the economic conditions of Tunisians living in the peripheries is less to do with the support available from international partners and more to do with how Tunisia’s internal state apparatus operates. At one and the same time, Tunisia’s government is centralised yet riven by fragmentation. This, combined with its emphasis on security over socioeconomic development, has led to little progress in assisting the peripheries.

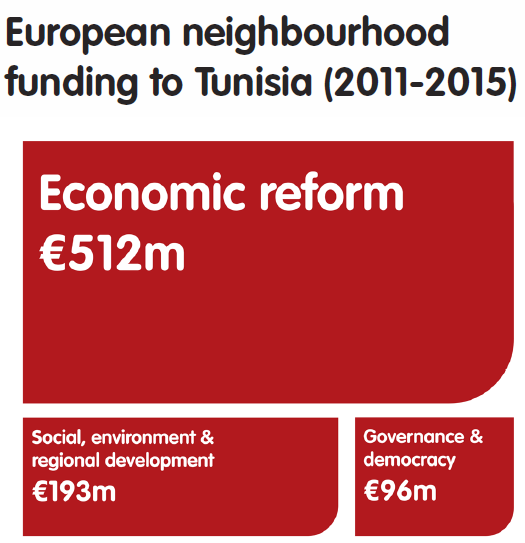

Money’s not too tight to mention

But the problem is not one of money – Tunisia has been able to rely on its international partners for support since 2011. Instead, the country needs to do several things to get its house in order: rethink its governance processes in order to implement a more coherent and coordinated development strategy; deliver the pre-existing projects which have earmarked funding; develop stronger political will to implement reforms; and introduce a new social contract that includes the population in the peripheries.

Between 2011 and 2015, Tunisia was the recipient of generous capital inflows from all the major international financial institutions, development banks, and international partners, amounting to almost $7 billion in various forms. Capital inflows received by 2015 came to almost 15 percent of GDP. In 2016, international partners reaffirmed their support: the World Bank established a new country partnership framework that will provide Tunisia with up to $5 billion in loans to help restore economic growth, create jobs for young people, and reduce the disparities between the coastal centres and the underdeveloped regions.

Also in 2016, the International Monetary Fund approved an extended fund facility of $2.8 billion across four years to support economic reform in Tunisia. Finally, during the most recent international conference to support the five-year development plan (2016-2020), Tunisia signed $4.3 billion in project-finance deals. The total financial support pledged to Tunisia by participating countries and financial institutions which took part in the conference therefore totals $14 billion, equivalent to 35 percent of GDP. The European Union and its member states remain Tunisia’s most prominent partners: the EU pledged $860 million by 2020, and the European Investment Bank promised loans of $3.1 billion by 2020.

Despite this flow of money and these cooperation mechanisms, Tunisian governments have so far failed to achieve the much-needed regional development that would considerably improve daily life and economic conditions in the peripheries. The post-revolution governments have prioritised underdeveloped regions, conferring on them 60 percent of the total of TND 1,547 million allocated to the Regional Development Programme (RDP) between 2011 and 2015. Particular attention has been given to the eight least developed regions: Jendouba, Kasserine, Kairouan, Siliana, Sidi Bouzid, Kef, Tataouine and Béja, which received 30 percent of the investment allocated to the RDP over the same period. Despite attempts to improve the completion rates for funded public projects, these have remained low and failed to meet popular expectations. In Kasserine completions stand at 47 percent, in Kairouan at 41 percent, in Sidi Bouzid at 41 percent and in Medenine at 28 percent. Meanwhile, private investments have remained targeted at the coastal regions, perpetuating the existing imbalances. The end result is that the socioeconomic situation in the peripheries has remained roughly unchanged since 2011.

Many factors explain the limited absorptive capacities of these regions. Among them are: lack of skilled and empowered staff at the local level able to manage and to follow up a large number of projects and large amounts of money; failure of the current regional development governance system to manage large budgets; unclear land tenure and property rights; a weak private sector in these regions which is uncompetitive and unable to win public contracts; security challenges and social instability that deter companies from investing in these regions and implementing local development projects; a degraded rule of law environment that limits the attractiveness of these regions to business.

Let down by the system

In March 2013 the Tunisian government set up a ‘general authority’ for the follow-up of public programmes to better ensure the delivery of public projects. This delivery unit, funded by the World Bank, is to work on the removal of administrative barriers and cutting long procedural delays. However, Tunisia needs more than a simple unit to deal with impediments to investment. It needs a development strategy for the peripheries, deploying innovative governance instruments that would improve inter-ministerial cooperation.

The long legacy of inefficient inter-ministerial cooperation has hampered the emergence of a coherent vision for regional development. As long as all the ministries and every national and regional administration fail to align or coordinate a multi-sectorial development strategy, regional development will lag. Regional administrations themselves are under dual supervision: under the supervision of the relevant national sectorial administration, and also under the control of governors – state representatives holding power at the regional level. The governors’ mission has historically been to supervise coordination between regional administrations, facilitate development and ensure security. But this mission has proved difficult to achieve. Experience instead shows that, worried about their careers, governors tend to favour security over development.

A senior state official explains the situation thus: “In Tunisia, the central level is predominant in decision-making. The problem is that there is no strategy for regional development, only sectorial policies for each region”. This view is corroborated by a European expert working on regional development: “The balance of power between the coastal regions and peripheries is so off-balance. Tunisian regions don’t have advocates who speak on their behalf. We should start from there and help these advocates emerge.”

Illustrative of this is the conflict that has pitted the state against the Association for the Protection of Jemna’s Oasis. In 2011, the residents of Jemna, a small town in the south of Tunisia, took control of state-owned land that the central government used to lease at low prices to private operators, who had formerly capitalised unfairly on their political connections. Indeed, under the Bourguiba and Ben Ali regimes, state-owned lands were regularly used to establish clientelist relationships and co-opt economic elites and prominent local figures. Operating under a cooperative economy model, without public support, investment incentives or tax deductions, the Association has developed the land, hired local workers, and reinvested revenues back into the community. However, under Youssef Chahed the government has refused to acknowledge the experiment, and is instead trying to end it. In this context, land reform, and a legislative framework that would encourage similar cooperative experiments, could promote development and job creation in these regions.

Strengthening EU-Tunisia mechanisms

Since 2011, Tunisia’s international partners have demonstrated their support for the country by pledging funding to sustain future regional development projects in Tunisia. What is required now are both reforms and the political will to back them up, as well as a genuine effort on the Tunisian side to coordinate international partners.

Improving coordination

The lack of coordination within the Tunisian authorities has been regularly noted by European diplomats who have participated in the sessions of the international coordination mechanisms. Tunisian officials frequently arrive at meetings with what one European expert called “shopping lists” in lieu of well-defined and budgeted strategies, without prior consultation or coordination of work among themselves.

Internationally, current mechanisms include the G7+ partnership, and a prospective Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) agreement with the EU. The G7 together with EU and international financial institutions (IFI) in June 2016 launched a partnership for coordinating economic assistance to Tunisia focusing on economic and governance reform. The G7+ partnership emphasises the European Parliament resolution which called for the “adoption of regulatory frameworks aimed at facilitating the absorption of European support and of all international financial institutions”.

Simultaneously, state authorities are concerned about the risk of social protest if they repress smugglers. The army has succeeded in maintaining – relatively speaking – its credibility, focusing mainly on its task of border policing (in spite of cases of soldiers’ involvement in corruption). But the interior security forces enjoy much less trust than the army does, having become “entrepreneurs of insecurity” as they extended their role beyond law enforcement to deal with social protest through negotiating bribes and selling protection. This has negatively impacted on the legitimacy of the security forces, as smugglers and traders perceived it as a way to reinvent the old arrangements through the co-optation of a happy few and the exclusion of others.

Second, the outbreak of armed conflict in neighbouring Libya in 2014 generated new uncertainty in Tunisia’s periphery regions, as competition grew between smuggling networks looking for protection in Libya. Indeed, cities in the west of Libya have always played a major “city-entrepot” role for the border economy, connecting southern Tunisian cities to the global illicit economy and ensuring supply to the Tunisian market. The border economy exerts a magnetic pull on militias attracted by the prospect of controlling and benefiting from illicit flows: approximately 15 Libyan militias are positioning along the border with Tunisia. This greatly complicates Tunisian authorities’ efforts to coordinate with their Libyan counterparts on border security.

Finally, the situation was complicated further in 2014 when jihadi groups affiliated to ISIS sought to replicate what al- Qaeda did at the Tunisia-Algeria border and establish a foothold in the Libyan city of Sabratha. The jihadi group tried to attract Tunisian jihadis who sought to flee the country, especially after the crackdown on Ansar al-Sharia, a Tunisian Salafi jihadi group, labelled a terrorist organisation by the Ennahda-led government in August 2013. These jihadi groups affiliated to ISIS tried to find an anchor in the Tunisia-Libya borderland through taking advantage of the rivalry between tribes and smuggling networks in a context of economic hardship. A review of the 26 assailants from Ben Guerdane who tried to capture this border town on 7 March 2016 revealed an overrepresentation of youth originating from the R’baya’ tribe. Historically dominated by the powerful tribe of Twazine which is in control of the cross-border trade around Ben Guerdane, the marginalisation of the R’baya’ was exacerbated by an unresolved and a long-lasting conflict over land ownership. R’baya’ smugglers, traffickers and individuals ousted from the border economy following heavy-handed security measures found in jihad a narrative that allows them to resist the state and to pursue these old tribal rivalries.

Security in the peripheries is therefore directly threatened by the exacerbation of pre-existing fault lines that feed on the dynamics of the jihadisation of local conflicts, in a context of a weak central state, economic hardship, and an emerging violence-shaped economic order.

Solving the security-economy conundrum

The tightening of controls at the Algerian and Libyan borders has resulted in the exclusion of many operators from the border economy. According to a survey by International Alert, 80 percent of the respondents living in Ben Guerdane and Dhehiba, near the Libyan border, believe that being able to cross the border is now linked to corruption more than ever. A World Bank report on the informal economy in the Tunisian peripheries highlighted the risks of increasing securitisation since 2013, noting that in the absence of concrete measures to address the economic and regulatory differences in terms of tariffs, tax levels and subsidies on either side of the border, tighter controls would increase corruption among state agents over time, and eventually undermine government control.

At the time of the popular uprisings, a number of joint projects were in train that would have helped regulate and legalise cross-border trade. But a planned free trade zone between Ben Guerdane and the border crossing of Ras Jedir, as well as the convertibility of national currencies, have never materialised. The securitisation of the borders and particularly the frequent closure of the border crossings at the Tunisia-Libya border has resulted in the suspension of cross-border trade and negatively impacted on the social and economic conditions in the periphery. Informal trade represents an important part of bilateral trade with neighbouring Libya and Algeria, accounting for more than half of official trade with Libya and for more than the total official trade with Algeria. Informal trade is one of the most important activities in the border regions. For example, a large part of the fuel consumed in Tunisia is imported from Algeria and Libya. In the governorate of Medenine, 20 percent of the working-age population works in the informal trade, approximately 83 percent of which are from Ben Guerdane.

The importance of the informal economy has increased since 2011, given the diminution of economic opportunities and the end of migration to Libya. Since the fall of Gaddafi and the deterioration of the security situation, 40,000 Tunisian workers have left Libya. For more than four decades Libya was a major destination for Tunisian seasonal workers from the periphery regions who helped meet the demand for labour in their oil-producing neighbour. The loss of these incomes has increased poverty and dissatisfaction among large swathes of the population: 10,000-15,000 families have received no income since 2011 because of the crisis in Libya.

The securitisation of cross-border trade has reinforced the prevalent perception that protest and migration are two of the dwindling options left to disenfranchised youth. In November 2016, a general strike was organised under the banner of ‘Let Ben Guerdane survive’. This protest lasted several months and received the support of neighbouring border towns. The lack of economic development leads to increased emigration, often illegal, as sadly exemplified by one of the many tragic boat capsizings that killed 12 young people from Ben Guerdane off the Libyan coast in July 2016. Meanwhile, negotiations are taking place between a Tunisian civil society delegation and the representatives of Libyan border towns in order to reach an agreement on reopening the border crossing of Ras Jedir. This follows a series of protests throughout 2016 in Ben Guerdane against the interruption of cross-border trade as well as the killing of several smugglers by the military.

The security-centred approach to ensuring stability is not a durable solution. Inhabitants of the peripheries have come to conclude that the central state views these regions as mere ‘buffer zones’ and their inhabitants as second-class citizens. They consider that calls for security are used to justify the security forces’ heavy-handedness and that they stigmatise the peripheries as hotbeds of jihadism. Many of those who feel alienated turn to Libya and Algeria for subsistence, rather than their own country of Tunisia. The experience of one young smuggler who was cut out of the border economy captures the bind many people find themselves in: “I went to the capital, Tunis, to look for a job. There, a policeman asked for my documentation. He took my ID card and told me: ‘You are from Kasserine. What are you doing here?’ I replied: ‘Do I need a visa to come to Tunis?’ It is as if we are living in two different countries.”

Reforming regional governance

The failure of the post-2011 governments to successfully implement projects and improve the economic conditions of Tunisians living in the peripheries is less to do with the support available from international partners and more to do with how Tunisia’s internal state apparatus operates. At one and the same time, Tunisia’s government is centralised yet riven by fragmentation. This, combined with its emphasis on security over socioeconomic development, has led to little progress in assisting the peripheries.

Money’s not too tight to mention

But the problem is not one of money – Tunisia has been able to rely on its international partners for support since 2011. Instead, the country needs to do several things to get its house in order: rethink its governance processes in order to implement a more coherent and coordinated development strategy; deliver the pre-existing projects which have earmarked funding; develop stronger political will to implement reforms; and introduce a new social contract that includes the population in the peripheries.

Between 2011 and 2015, Tunisia was the recipient of generous capital inflows from all the major international financial institutions, development banks, and international partners, amounting to almost $7 billion in various forms. Capital inflows received by 2015 came to almost 15 percent of GDP. In 2016, international partners reaffirmed their support: the World Bank established a new country partnership framework that will provide Tunisia with up to $5 billion in loans to help restore economic growth, create jobs for young people, and reduce the disparities between the coastal centres and the underdeveloped regions.

Also in 2016, the International Monetary Fund approved an extended fund facility of $2.8 billion across four years to support economic reform in Tunisia. Finally, during the most recent international conference to support the five-year development plan (2016-2020), Tunisia signed $4.3 billion in project-finance deals. The total financial support pledged to Tunisia by participating countries and financial institutions which took part in the conference therefore totals $14 billion, equivalent to 35 percent of GDP. The European Union and its member states remain Tunisia’s most prominent partners: the EU pledged $860 million by 2020, and the European Investment Bank promised loans of $3.1 billion by 2020.