The New Turkey: Making Sense of Turkish Decision-Making

9 May 2018

By Aaron Stein for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Atlantic Council in April 2018.

The erosion of democratic institutions in Turkey has prompted quiet discussion in many Western countries about Ankara’s place in the transatlantic community and the future of Turkish policy making. There is little debate about Turkey’s importance for projecting power into the Black Sea and for helping to contain a revanchist Russia, but Ankara’s poor relations with the United States and many European countries, combined with close cooperation with Moscow in Syria, have raised questions about the drivers of Turkish decision-making. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has pursued a balanced foreign policy premised on a sustained effort to deepen Turkish ties with regional countries while preserving relations with the transatlantic community and powers in Turkey’s near abroad.

The challenge for Western governments does not stem from Turkey’s efforts to deepen relations with its neighbors. Instead, the issue for the United States and Europe is how Turkish politicians are using foreign policy as a tool for populist political gain—and how this trend could erode domestic support for Turkey’s alliance with Europe and the United States.

This trend in Turkish politics is linked to the collapse of Turkey’s democratic institutions, following a failed coup attempt in July 2016, and a concurrent wave of terrorist attacks linked to the civil war in Syria. In the wake of the coup attempt, for example, Ankara has demonized the United States for refusing to extradite Fethullah Gulen, the exiled imam blamed for planning the putsch attempt, and for US military support given to a Syrian Kurdish militia, linked to the insurgent Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). In parallel, Turkish relations with different European countries have deteriorated amid disputes about PKK-linked activities,1 AKP campaign rallies in different European capitals, and concerns about AKP meddling in European Union (EU) politics..2

To better understand the relationship between Turkish policy making and public opinion, the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center worked with Metropoll, a Turkey-based independent polling firm, to gauge public opinion about the country’s relationship with its neighbors and allies. Specifically, the poll asked respondents about NATO’s importance for Turkish security, the European Union accession process, and which European country is Turkey’s closest ally.3 The intent of this paper is to better understand how Turkish citizens view these three interrelated issues and how this may impact governmental policy making.4

In general, the data show that the Turkish public is suspicious of allies in Europe, a finding that is also reflected in numerous other polls conducted on public opinion in Turkey.5 Turkish politicians have an incentive to play on this predisposed outlook, particularly during times of policy disagreement between Ankara and its transatlantic allies.

On the question of NATO, a plurality of Turkish citizens still believe that the Alliance is important for Turkish security; however, the same cannot be said about Turkish perceptions of the European Union accession process and Turkish points of view about European allies.

Polling data clearly indicate that Turkish voters are most concerned about their own economic well-being and the economy. This creates an odd dynamic for Turkish politicians, whereby they face little or no repercussion for anti-Western rhetoric and policy so long as Turkey’s economic relations with Europe are not negatively impacted. This dynamic poses a unique challenge for the United States and Europe. Ankara is a treaty ally. However, traditional mechanisms to compel changes to Turkish policy, like the European Union accession process or joint condemnation of illiberal governance, have proved ineffective in altering Turkish decision-making. Moreover, there does not appear to be enough internal, bottom-up pressure on Turkish politicians to effect policy making, unless the economy is threatened. For allies, conditioned to try to reach political consensus with Turkey, the toolbox is now limited, unless coercive policies that threaten the Turkish economy are implemented. However, any such action risks populist backlash and exacerbating the negative attitudes amongst the Turkish public about its traditional allies.

This report is divided into three analytical sections detailing the findings of the opinion poll; how those findings have impacted and will continue to impact Turkish decision making; the role the economy plays in helping to shape Turkish policy; and the implications of the results for the United States.

Is NATO important for Turkish security

The erosion of democratic institutions in Turkey has prompted quiet discussion in many Western countries about Ankara’s place in the transatlantic community and the future of Turkish policy making. There is little debate about Turkey’s importance for projecting power into the Black Sea and for helping to contain a revanchist Russia, but Ankara’s poor relations with the United States and many European countries, combined with close cooperation with Moscow in Syria, have raised questions about the drivers of Turkish decision-making. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has pursued a balanced foreign policy premised on a sustained effort to deepen Turkish ties with regional countries while preserving relations with the transatlantic community and powers in Turkey’s near abroad.

The challenge for Western governments does not stem from Turkey’s efforts to deepen relations with its neighbors. Instead, the issue for the United States and Europe is how Turkish politicians are using foreign policy as a tool for populist political gain—and how this trend could erode domestic support for Turkey’s alliance with Europe and the United States.

This trend in Turkish politics is linked to the collapse of Turkey’s democratic institutions, following a failed coup attempt in July 2016, and a concurrent wave of terrorist attacks linked to the civil war in Syria. In the wake of the coup attempt, for example, Ankara has demonized the United States for refusing to extradite Fethullah Gulen, the exiled imam blamed for planning the putsch attempt, and for US military support given to a Syrian Kurdish militia, linked to the insurgent Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). In parallel, Turkish relations with different European countries have deteriorated amid disputes about PKK-linked activities,1 AKP campaign rallies in different European capitals, and concerns about AKP meddling in European Union (EU) politics..2

To better understand the relationship between Turkish policy making and public opinion, the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center worked with Metropoll, a Turkey-based independent polling firm, to gauge public opinion about the country’s relationship with its neighbors and allies. Specifically, the poll asked respondents about NATO’s importance for Turkish security, the European Union accession process, and which European country is Turkey’s closest ally.3 The intent of this paper is to better understand how Turkish citizens view these three interrelated issues and how this may impact governmental policy making.4

In general, the data show that the Turkish public is suspicious of allies in Europe, a finding that is also reflected in numerous other polls conducted on public opinion in Turkey.5 Turkish politicians have an incentive to play on this predisposed outlook, particularly during times of policy disagreement between Ankara and its transatlantic allies.

On the question of NATO, a plurality of Turkish citizens still believe that the Alliance is important for Turkish security; however, the same cannot be said about Turkish perceptions of the European Union accession process and Turkish points of view about European allies.

Polling data clearly indicate that Turkish voters are most concerned about their own economic well-being and the economy. This creates an odd dynamic for Turkish politicians, whereby they face little or no repercussion for anti-Western rhetoric and policy so long as Turkey’s economic relations with Europe are not negatively impacted. This dynamic poses a unique challenge for the United States and Europe. Ankara is a treaty ally. However, traditional mechanisms to compel changes to Turkish policy, like the European Union accession process or joint condemnation of illiberal governance, have proved ineffective in altering Turkish decision-making. Moreover, there does not appear to be enough internal, bottom-up pressure on Turkish politicians to effect policy making, unless the economy is threatened. For allies, conditioned to try to reach political consensus with Turkey, the toolbox is now limited, unless coercive policies that threaten the Turkish economy are implemented. However, any such action risks populist backlash and exacerbating the negative attitudes amongst the Turkish public about its traditional allies.

This report is divided into three analytical sections detailing the findings of the opinion poll; how those findings have impacted and will continue to impact Turkish decision making; the role the economy plays in helping to shape Turkish policy; and the implications of the results for the United States.

Is NATO important for Turkish security

Suspicious of NATO: Accepting of the Security Benefit

Turkey joined NATO in 1952 to guarantee Turkish security from the Soviet Union. Yet Turkish policy makers have always feared being totally reliant on allies for defense, and therefore pushed to host NATO infrastructure and play an active role in shaping NATO policy.

Turkey’s historic concerns about alliance solidarity have prompted Ankara’s active NATO role, and its lobbying for policies that are beneficial for its own national interests. However, these efforts have shifted following the end of the Cold War, and Turkish policy makers are more willing to act independently of the Alliance and to challenge individual members. In the past year, for example, Turkey’s relationship with NATO members Germany,6 the Netherlands,7 Italy,8 the Czech Republic,9 and Greece10 have been strained in addition to the separate and more challenging issues Ankara and the United Sates are now facing.11 The day-to-day working relationship within the Alliance is largely insulated from these broader, bilateral political problems with NATO members. However, the often-toxic narrative in the Turkish press about these mini-crises undermines trust in allies. Thus, while the narrow, bilateral spats have nothing to do with the Alliance, and the day-to-day functions of NATO are insulated, the atmosphere erodes public trust in multilateral institutions.

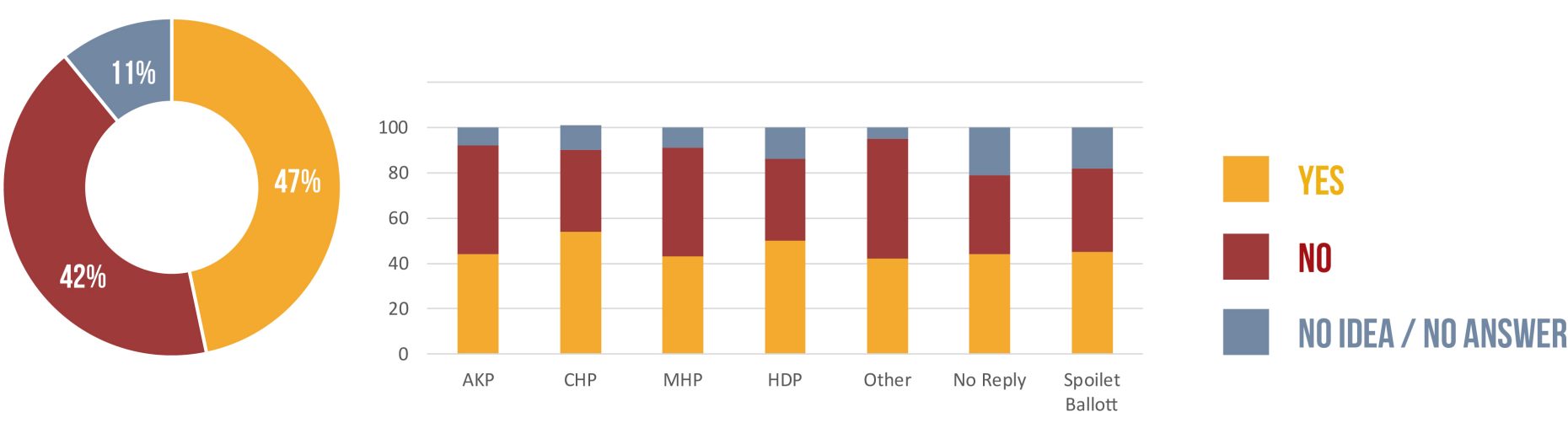

The opinion poll data suggests that a plurality (46.7 percent) of Turkish citizens believe NATO is important for Turkish security; however, a larger percentage of AKP and Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) voters believe that NATO is not important for Turkish security (48.2 percent of AKP supporters do not believe NATO is important for Turkish security, compared to 47.8 percent of MHP supporters). These numbers suggest that the AKP/MHP have a political incentive to get tough with the Alliance, which may explain why the Turkish government has, at times, criticized NATO for events in Syria.12 Nonetheless, when doing so, the AKP has sought to draw a distinction between Turkish dissatisfaction with the United States and the Alliance as a whole.

Members of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition party in the country, showed the most favorable attitude toward NATO, with 56.7 percent of party members saying the Alliance was important for Turkish security. The Kurdish-majority Peoples’ Democratic Party, or HDP, also scores higher than the AKP/MHP, with 50 percent of respondents believing that NATO is important for Turkish security. The majority support from these two parties is encouraging, but the relatively high number of respondents that do not believe NATO is important for Turkish security suggests that the public is lukewarm about the value of the Alliance. This is not surprising, given the level of anti-Western rhetoric that permeates the Turkish political debate and Ankara’s history of suspicion of even its closest allies’ intentions.

The issue of Turkey’s alliances is salient in the parties’ campaigns for the November 2019 election. The survey data suggest that the AKP/MHP alliance would face some backlash from the voters if it pushed for policies radically incongruent with Turkey’s NATO membership. The two parties’ constituencies have a sizable number of voters who think of NATO as important for Turkish security.13

Will Turkey ever join the European Union

Turkey joined NATO in 1952 to guarantee Turkish security from the Soviet Union. Yet Turkish policy makers have always feared being totally reliant on allies for defense, and therefore pushed to host NATO infrastructure and play an active role in shaping NATO policy.

Turkey’s historic concerns about alliance solidarity have prompted Ankara’s active NATO role, and its lobbying for policies that are beneficial for its own national interests. However, these efforts have shifted following the end of the Cold War, and Turkish policy makers are more willing to act independently of the Alliance and to challenge individual members. In the past year, for example, Turkey’s relationship with NATO members Germany,6 the Netherlands,7 Italy,8 the Czech Republic,9 and Greece10 have been strained in addition to the separate and more challenging issues Ankara and the United Sates are now facing.11 The day-to-day working relationship within the Alliance is largely insulated from these broader, bilateral political problems with NATO members. However, the often-toxic narrative in the Turkish press about these mini-crises undermines trust in allies. Thus, while the narrow, bilateral spats have nothing to do with the Alliance, and the day-to-day functions of NATO are insulated, the atmosphere erodes public trust in multilateral institutions.

The opinion poll data suggests that a plurality (46.7 percent) of Turkish citizens believe NATO is important for Turkish security; however, a larger percentage of AKP and Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) voters believe that NATO is not important for Turkish security (48.2 percent of AKP supporters do not believe NATO is important for Turkish security, compared to 47.8 percent of MHP supporters). These numbers suggest that the AKP/MHP have a political incentive to get tough with the Alliance, which may explain why the Turkish government has, at times, criticized NATO for events in Syria.12 Nonetheless, when doing so, the AKP has sought to draw a distinction between Turkish dissatisfaction with the United States and the Alliance as a whole.

Members of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition party in the country, showed the most favorable attitude toward NATO, with 56.7 percent of party members saying the Alliance was important for Turkish security. The Kurdish-majority Peoples’ Democratic Party, or HDP, also scores higher than the AKP/MHP, with 50 percent of respondents believing that NATO is important for Turkish security. The majority support from these two parties is encouraging, but the relatively high number of respondents that do not believe NATO is important for Turkish security suggests that the public is lukewarm about the value of the Alliance. This is not surprising, given the level of anti-Western rhetoric that permeates the Turkish political debate and Ankara’s history of suspicion of even its closest allies’ intentions.

The issue of Turkey’s alliances is salient in the parties’ campaigns for the November 2019 election. The survey data suggest that the AKP/MHP alliance would face some backlash from the voters if it pushed for policies radically incongruent with Turkey’s NATO membership. The two parties’ constituencies have a sizable number of voters who think of NATO as important for Turkish security.13

Will Turkey ever join the European Union

The European Union: The Zombie Process

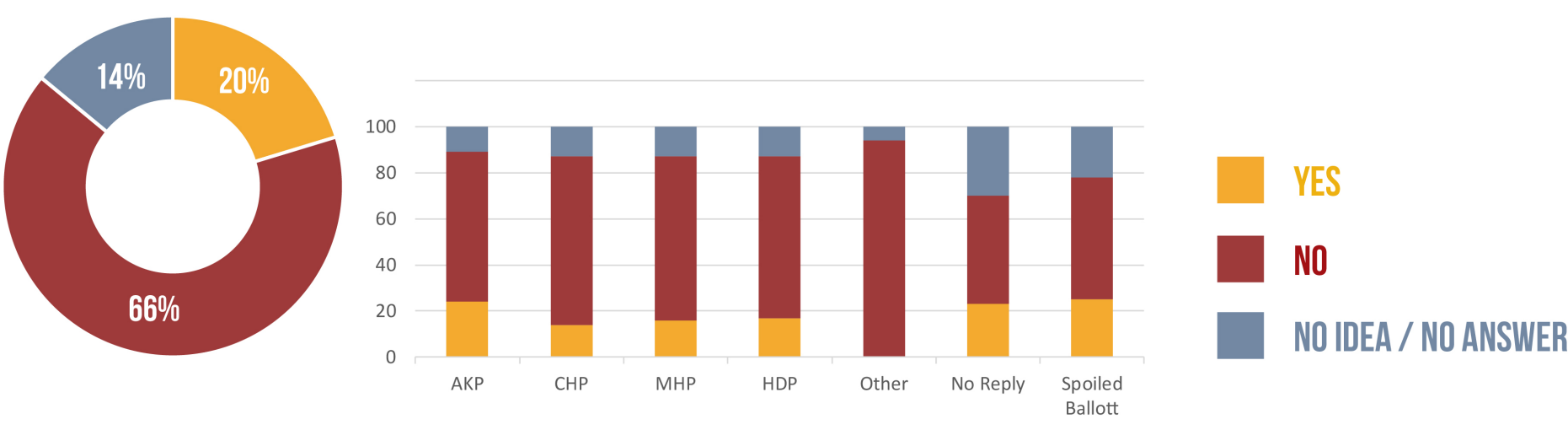

The Turkish electorate is rarely united. According to the Center for American Progress, “Turks are deeply divided along partisan and ideological lines regarding the overall direction of the country, the economy, and President Erdogan’s job performance.”14 However, on the question of whether Turkey will ever join the European Union, respondents from every political party overwhelmingly answered “no.”

The AKP continues to include EU accession in its political platform, despite the very realistic sentiment amongst its voters that the prospect of membership is remote. The EU process has become a social wedge issue in Turkey and a useful political foil for the AKP. At the same time, public opinion polling underscores that the top issue for Turkish voters is the economy. As of 2017, the European Union remained Turkey’s largest source of foreign direct investment. The EU process, and in particular, negotiations for an updated Customs Union15 is an important issue for the AKP to manage—and helps to frame how Turkey formulates its Europe policy.

The German government, for example, vetoed16 future talks on the updated Customs Union in August 2017, following a series of arrests of German citizens in Turkey.17 In a narrower example, Turkish policy makers sought to silo bilateral political tensions with the Netherlands after a dispute over the refusal to allow the AKP to hold a rally in Rotterdam resulted in the expulsion of a Turkish minister. Following the incident, Turkey imposed so-called diplomatic sanctions, which included a ban on diplomatic flights from the Netherlands and a refusal to allow the Dutch ambassador to return to Turkey. The Turkish parliament also took the symbolic step of dissolving a parliamentary friendship group.18 However, these measures did not include any economic sanctions.19 Moreover, in a clear example of walling off economic issues from bilateral political tensions, Omer Celik, Turkey’s ambassador to the EU, sought to reassure investors, telling reporters, “The private sector, business world, tourists and the people of the Netherlands are not a part of the crisis.”20

The push-and-pull between the Turkish public’s negative opinions toward the process, combined with the very real economic reason to maintain elements of Turkey’s relationship help explain Turkish policy. For Turkish policy makers focused on perpetuating a nationalist, inward-looking narrative of a Turkey under siege from hostile external powers, the moribund accession process helps perpetuate an effective political message that external powers are colluding to undermine Turkey over ill-defined concerns about the implications of a “strong Turkey” for transatlantic security. However, the AKP must also ensure that Turkish economic relations with the bloc are not undermined—an outcome that would be politically damaging.

Which European country is Turkey's closest ally

The Turkish electorate is rarely united. According to the Center for American Progress, “Turks are deeply divided along partisan and ideological lines regarding the overall direction of the country, the economy, and President Erdogan’s job performance.”14 However, on the question of whether Turkey will ever join the European Union, respondents from every political party overwhelmingly answered “no.”

The AKP continues to include EU accession in its political platform, despite the very realistic sentiment amongst its voters that the prospect of membership is remote. The EU process has become a social wedge issue in Turkey and a useful political foil for the AKP. At the same time, public opinion polling underscores that the top issue for Turkish voters is the economy. As of 2017, the European Union remained Turkey’s largest source of foreign direct investment. The EU process, and in particular, negotiations for an updated Customs Union15 is an important issue for the AKP to manage—and helps to frame how Turkey formulates its Europe policy.

The German government, for example, vetoed16 future talks on the updated Customs Union in August 2017, following a series of arrests of German citizens in Turkey.17 In a narrower example, Turkish policy makers sought to silo bilateral political tensions with the Netherlands after a dispute over the refusal to allow the AKP to hold a rally in Rotterdam resulted in the expulsion of a Turkish minister. Following the incident, Turkey imposed so-called diplomatic sanctions, which included a ban on diplomatic flights from the Netherlands and a refusal to allow the Dutch ambassador to return to Turkey. The Turkish parliament also took the symbolic step of dissolving a parliamentary friendship group.18 However, these measures did not include any economic sanctions.19 Moreover, in a clear example of walling off economic issues from bilateral political tensions, Omer Celik, Turkey’s ambassador to the EU, sought to reassure investors, telling reporters, “The private sector, business world, tourists and the people of the Netherlands are not a part of the crisis.”20

The push-and-pull between the Turkish public’s negative opinions toward the process, combined with the very real economic reason to maintain elements of Turkey’s relationship help explain Turkish policy. For Turkish policy makers focused on perpetuating a nationalist, inward-looking narrative of a Turkey under siege from hostile external powers, the moribund accession process helps perpetuate an effective political message that external powers are colluding to undermine Turkey over ill-defined concerns about the implications of a “strong Turkey” for transatlantic security. However, the AKP must also ensure that Turkish economic relations with the bloc are not undermined—an outcome that would be politically damaging.

Which European country is Turkey's closest ally

Turkey: Suspicious of Everyone

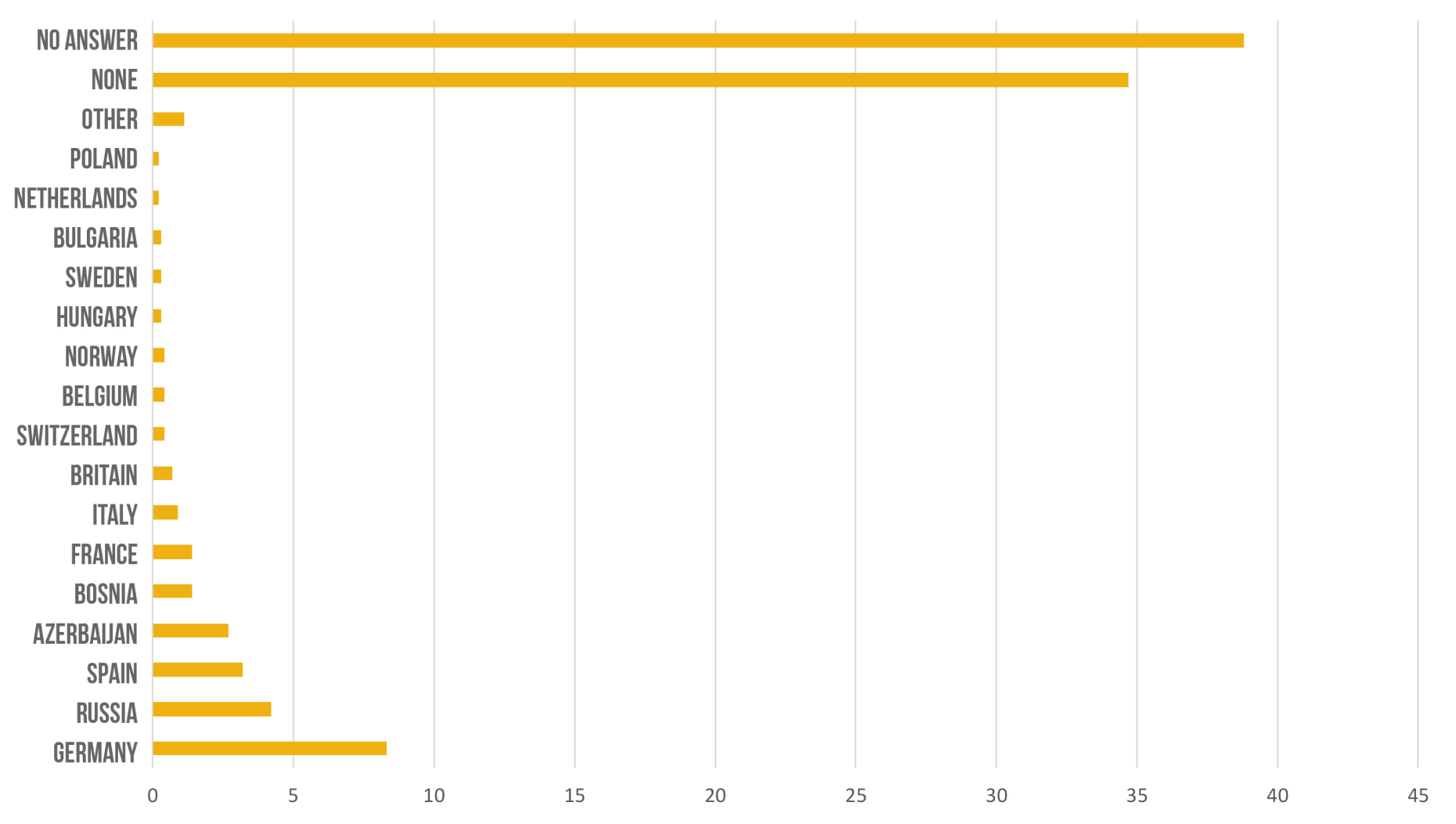

The data about Turkey’s EU accession process fits with Turkish opinion about Ankara’s alliances with the European countries. Unsurprisingly, Turkish citizens do not have a positive view of Europe. In response to the question “Which European country is Turkey’s closest ally?,” the highest scorer, Germany, was only named by 8.3 percent of respondents. The largest response (34.7 percent), other than “no idea/no answer” was “no ally.”

The survey data are congruent with different public opinion polls conducted in Turkey. For example, the Center for American Progress found that Turkish public opinion has low favorability ratings of Europe as a whole with only 21 percent of respondents saying they had a favorable view. The Turkish public is also skeptical of Russia, with only 4.2 percent of respondents identifying Russia as a Turkish ally.

The Turkish public is notoriously suspicious of outsiders and numerous polls reinforce this finding: Turkish citizens are genuinely distrustful of other countries. This distrust, however, has led policy makers to pursue policies that bind Turkey to Western institutions, such as NATO and the European community. In the case of the former—and related to this report’s findings on NATO—Ankara’s instincts were to seek out tangible commitments from the Alliance deployed on Turkish territory. For example, Turkey is one of five members that host US nuclear weapons in Europe, and, more recently, Ankara is a framework nation of the Alliance’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) and has offered to lead the group in 2021.21

The data suggest that Turkish politicians have little to lose politically from lambasting Turkish allies in Europe. The Turkish public does not trust European countries and, in general, has low favorability ratings of the entire European continent. However, the general distrust has, historically, galvanized Turkish policy makers to try to deepen engagement with allies. There are signs that the AKP is breaking with this tradition and taking advantage of these suspicions for its own domestic political advantage.

The Future: Guns or Butter?

The political trends in Turkey suggest that Erdogan will be elected to the executive presidency, which he created for himself, in November 2019 or in an early election. The polling indicates that Erdogan remains Turkey’s most popular politician.22 The AKP-MHP alliance is well-positioned to capitalize on the schisms amongst Turkey’s opposition voting blocs, to increase AKP control in parliament, and to ensure Erdogan’s electoral victory. The next election, however, will give way to a rarity in recent Turkish political history: a half-decade gap between elections.

The MHP may seek to increase appointees in Turkey’s Ministry of Interior, a historic right-wing bastion and the organization responsible for overseeing the Turkish national police and gendarmerie. This arrangement raises a broader question about how the AKP-MHP could approach the “Kurdish issue” following the election.

Public opinion data indicates that the Turkish electorate is concerned about terrorism, which suggests that the AKP-MHP have a political incentive to take a tough stand against the PKK. This political incentive fits nicely with the MHP’s historical approach to the PKK, its long-standing advocacy for no political compromise with the PKK, and an aggressive military-led approach to the issue. The combination of a potential prominent role for MHP in the Interior Ministry, combined with the public opinion data, suggests little political pressure to return to peace talks with the PKK.

Public concerns about the economy, the data suggest,will play a major role in setting the AKP’s future agenda. For example, while the Turkish public lists terrorism as Turkey’s “most important problem,” voters’ personal concerns about the economic situation dwarf security concerns, with 52.1 percent of respondents listing the “economy/making ends meets” as their main concern. For comparison, only 2.4 percent of respondents listed terrorism as an “important problem they face personally.”23

The data about Turkey’s EU accession process fits with Turkish opinion about Ankara’s alliances with the European countries. Unsurprisingly, Turkish citizens do not have a positive view of Europe. In response to the question “Which European country is Turkey’s closest ally?,” the highest scorer, Germany, was only named by 8.3 percent of respondents. The largest response (34.7 percent), other than “no idea/no answer” was “no ally.”

The survey data are congruent with different public opinion polls conducted in Turkey. For example, the Center for American Progress found that Turkish public opinion has low favorability ratings of Europe as a whole with only 21 percent of respondents saying they had a favorable view. The Turkish public is also skeptical of Russia, with only 4.2 percent of respondents identifying Russia as a Turkish ally.

The Turkish public is notoriously suspicious of outsiders and numerous polls reinforce this finding: Turkish citizens are genuinely distrustful of other countries. This distrust, however, has led policy makers to pursue policies that bind Turkey to Western institutions, such as NATO and the European community. In the case of the former—and related to this report’s findings on NATO—Ankara’s instincts were to seek out tangible commitments from the Alliance deployed on Turkish territory. For example, Turkey is one of five members that host US nuclear weapons in Europe, and, more recently, Ankara is a framework nation of the Alliance’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) and has offered to lead the group in 2021.21

The data suggest that Turkish politicians have little to lose politically from lambasting Turkish allies in Europe. The Turkish public does not trust European countries and, in general, has low favorability ratings of the entire European continent. However, the general distrust has, historically, galvanized Turkish policy makers to try to deepen engagement with allies. There are signs that the AKP is breaking with this tradition and taking advantage of these suspicions for its own domestic political advantage.

The Future: Guns or Butter?

The political trends in Turkey suggest that Erdogan will be elected to the executive presidency, which he created for himself, in November 2019 or in an early election. The polling indicates that Erdogan remains Turkey’s most popular politician.22 The AKP-MHP alliance is well-positioned to capitalize on the schisms amongst Turkey’s opposition voting blocs, to increase AKP control in parliament, and to ensure Erdogan’s electoral victory. The next election, however, will give way to a rarity in recent Turkish political history: a half-decade gap between elections.

The MHP may seek to increase appointees in Turkey’s Ministry of Interior, a historic right-wing bastion and the organization responsible for overseeing the Turkish national police and gendarmerie. This arrangement raises a broader question about how the AKP-MHP could approach the “Kurdish issue” following the election.

Public opinion data indicates that the Turkish electorate is concerned about terrorism, which suggests that the AKP-MHP have a political incentive to take a tough stand against the PKK. This political incentive fits nicely with the MHP’s historical approach to the PKK, its long-standing advocacy for no political compromise with the PKK, and an aggressive military-led approach to the issue. The combination of a potential prominent role for MHP in the Interior Ministry, combined with the public opinion data, suggests little political pressure to return to peace talks with the PKK.

Public concerns about the economy, the data suggest,will play a major role in setting the AKP’s future agenda. For example, while the Turkish public lists terrorism as Turkey’s “most important problem,” voters’ personal concerns about the economic situation dwarf security concerns, with 52.1 percent of respondents listing the “economy/making ends meets” as their main concern. For comparison, only 2.4 percent of respondents listed terrorism as an “important problem they face personally.”23

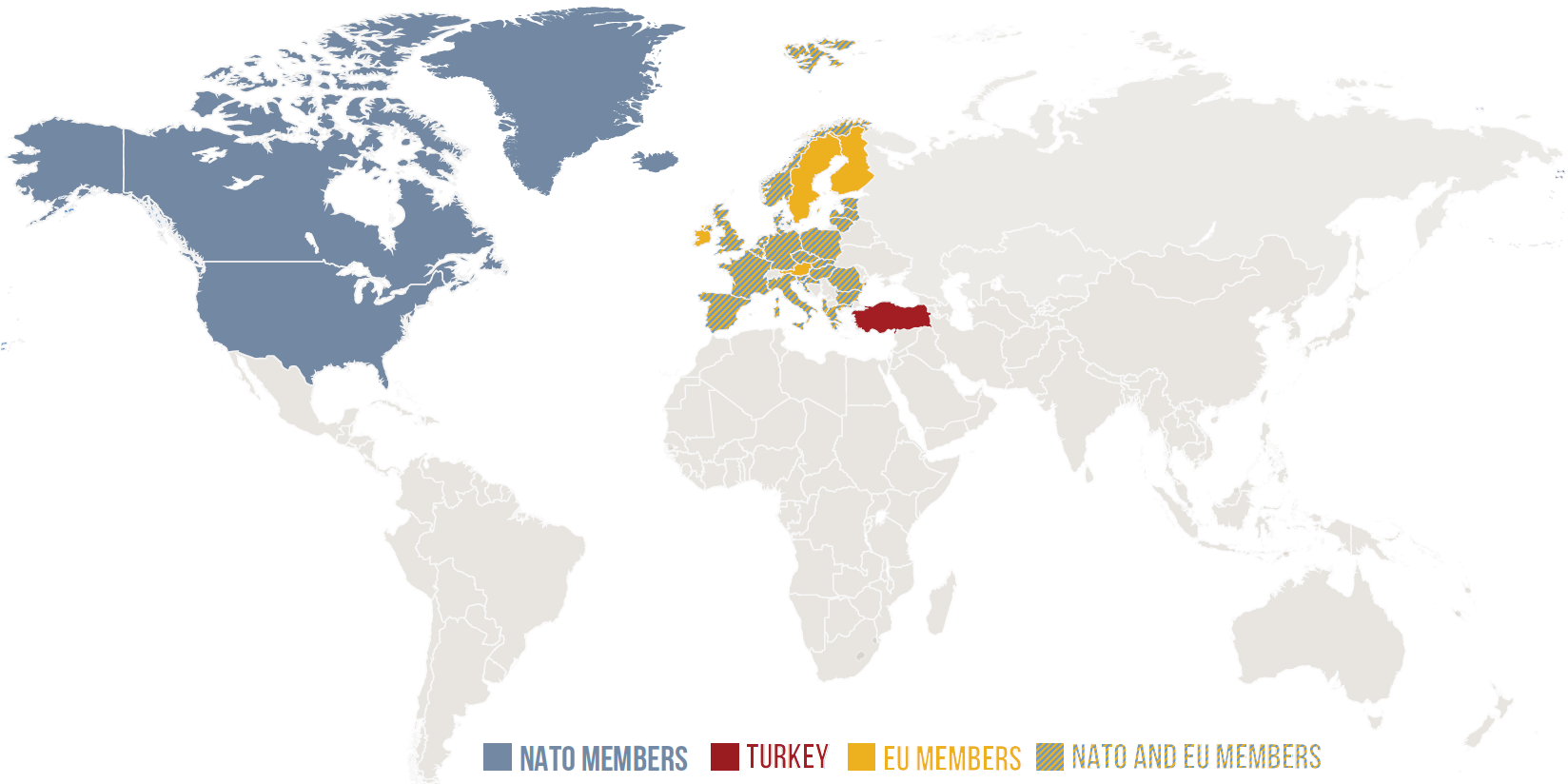

World map adapted from Felipe Menegaz/Wikimedia Commons

The dichotomy between the public’s general concern about security and the micro, individual-level focus on economic well-being helps explain elements of the AKP’s current policy vis-à-vis the PKK and also in its dealings with foreign allies. In general, the Turkish military’s counter-insurgency operations are limited to Turkey’s southeast and confined to Turkey’s Kurdish majority areas. At times, the PKK carries out terror attacks in Turkey’s central and western cities, as was most recently the case in Izmir in January 201724 and, perhaps, in Ankara in February 2018.25 In Turkey’s southeast, the military continues to deal with a sustained, low-level insurgency.26

To address Turkish economic concerns, the AKP has pursued a series of stimulus measures to increase the gross domestic product. The initial catalyst for Turkish action came just after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, amid broader concerns about whether the fall-out would negatively impact economic growth.27 The stimulus has helped grow the economy, but Turkey’s current account deficit has grown considerably, and inflation has remained in the low double digits. These factors prompted the International Monetary Fund, in February 2018, to warn that the economy may be overheating and then for international ratings agency Moody’s to downgrade Turkey’s sovereign debt rating.28 The challenge for the AKP will be how to take steps to “cool off” the economy, without crossing Erdogan’s demands for high growth rates and low interest rates.29

The economic data, mixed with public anxiety about the economy, suggest that the AKP-MHP government will focus considerable attention on ensuring continued economic growth. The second most salient issue for voters, terrorism (and security in general) will also impact Turkish foreign policy.

In Syria, the events of the past two years underscore Ankara’s commitment to use military force—and to work with both Russia and Iran—to facilitate cross-border military operations to combat Kurdish-led militias. The Turkish government has also accused Europe (and the United States) of being soft on terror and has adopted tactics that inflame tensions with much of Europe. Ankara has flooded Interpol with red notices, a tactic that has increased tensions with different European countries over concerns that the system is being abused.30

The Interpol notices have primarily focused on Kurdish individuals with links to the PKK (albeit without any definitive connection to insurgent attacks), followers of the Fethullah Gulen movement, and Turkish dissidents in Europe. In every reported instance, the prospect of extradition to Turkey is remote—if not impossible—and the accused is released. The releases, in turn, prompt Turkish backlash, which further fuels bilateral tensions between Turkey and different European countries. The tensions do not undermine AKP support with the Turkish public, and instead help to reinforce deeply ingrained views about Turkey’s relationship with allies.

Ankara’s actions may be dismissed as an aberration, or a byproduct of Erdogan’s singular push to consolidate his authority at all costs. To do so, Erdogan faces no serious political repercussions for criticizing the West and for hyping up the terror issue, so long as the voters’ most pressing concern, the economy, is well managed. This dichotomy helps to explain Turkish policy making—and where Ankara may be vulnerable to external coercion. Russia, for example, used economic sanctions following the Turkish downing of an SU 24 bomber in November 2015 to compel a change in Turkish policy in Syria. Russia also had the advantage of being able to offer Ankara something that it wanted: a relatively free hand to launch a cross border operation against Kurdish majority forces in Syria.

The German government, too, used economic coercion to force changes to Turkish policy, culminating in a rumored political agreement to release German nationals held in Turkey without serious evidence in exchange for defense, trade, and political concessions. The German-Turkish bilateral relationship remains far from “normal,” however, after the federal election in September 2017 resulted in a coalition between the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).31

The two parties are against Turkish membership in the European Union. French President Emmanuel Macron has adopted a similar policy, telling reporters at a joint press conference with Erdogan that Turkey should not be an EU member, but instead should have a “partnership” with the bloc.32

The moribund accession process is not a salient issue for Turkish voters. However, the continued German veto of further discussions with Turkey on an updated customs union, while far from an animating factor amongst the Turkish public, could negatively impact the Turkish economy. As a result, Ankara has both economic and political incentives to negotiate with Europe and to try to “reset” relations with Germany, following German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s pre-election announcement of a veto.33

This push-and-pull of the politically easy EU critiques typical in Turkey could undermine more important, longer-term policy issues, which would impact the issue voters most care about: the Turkish economy. The divergent, short-term instincts to bash outsiders versus the longer-term repercussions of Ankara’s aggressive rhetoric and actions explain Ankara’s rapid shifts in policy. For eight months in 2017, for example, Erdogan accused the German government of “actions no different to those of the Nazi period,” followed by an intimate foreign minister sit-down in Antalya to improve ties and to negotiate the release of an imprisoned German journalist, Deniz Yucel.

Implications for the United States: A New Relationship

The rapid changes in policy suggest a policy-making process in Turkey that is adrift and reactive to external events, but ultimately moored in economic and security self-interests. Ankara, for example, was able to overcome its difficulties with Russia to take action in Syria, in order to protect Turkey from a self-identified security threat in Syria.34

The Turkish government pursued a similar policy vis-à-vis Germany, wherein it continually has tried to balance between its narrow, populist political incentives to demonize the West while also managing to maintain functional economic relations. There are electoral reasons for this policy; however, the broader takeaway is that Ankara has settled on a policy of transactionalism with its allies and partners.

For the United States, the decrease in importance of the EU accession process deprives Washington of leverage to work to compel political change in Turkey. Specifically, the United States used to have a free ride on the European Union, particularly on addressing human rights-related issues, while at the same time working with Ankara on counter-terrorism-related issues.35

More recently, the twin collapses of the European Union process and the divergence in shared focus on US-Turkish counter-terrorism interests have undermined two key pillars of the relationship. Moreover, Ankara’s new transactional approach to foreign policy has led to a deepening of Turkish-Russian relations inside Syria and on defense procurement. In the case of the latter, Ankara’s purchase of Russian surface-to-air missiles36

risks undermining US-Turkish defense cooperation and eroding transatlantic trust in Turkey’s commitment to NATO. Yet, despite Alliance-wide dissatisfaction with the purchases and repeated warnings about the consequences, the Turkish government made the decision to go ahead with the purchase.

The polling data indicate that a narrow plurality (percentage) of AKP-MHP voters do not believe that NATO is beneficial for Turkish security. However, the number of voters that do believe the Alliance is important for Turkey is above 40 percent in both parties and, amongst all voters, just under 50 percent. In general, Turks do not have a favorable view of NATO, and so there is yet another divergence in political incentives that helps explain government rhetoric. At times of tension, the Turkish government faces few repercussions from voters when it challenges NATO. Yet, at the same time, Ankara’s day-to-day functions within the Alliance are insulated from much of this political rhetoric. Thus, the Turkish government faces few actual repercussions within the Alliance for its rhetoric, even though it may contribute to the broader Turkish distrust of the institution.

Conclusion: Coming to Terms with the New Turkey

The public opinion data cited in this paper represents a snapshot of Turkish public opinion. The findings help shed light on the internal, politically-driven aspects of Turkish policy making. The bigger question is whether the Turkish public’s unfavorable views of NATO will erode public perceptions about the Alliance’s value for security. Moreover, it is unclear if the constant negative reports about the United States and the Turkish government’s pervasive use of anti-American conspiracy theories to whip up populist support will have a spill-over effect and erode Turkish trust in supranational institutions, like NATO.

This report’s findings suggest that the most salient issue for Turkish policy makers in the near-to-medium term will be competent economic stewardship. Turkish distrust of outsiders provides policy makers with a low-risk, high-return incentive to blame Western countries and institutions for internal Turkish problems. The outcome, it appears, is that the Turkish government is comfortable with a policy of transactionalism with its traditional allies, even if those same allies have not yet come to terms with the fact that this is how the Turkish government now operates. The polling—and a long track-record of statements in power—clearly suggests that Ankara should not be expected to tout the benefits of its alliances and European allies.

The data suggest that the political incentives driving the current status quo remain in place, which is an outcome that should challenge long-held assumptions about the nature of Turkey’s relationship with Europe and, ultimately, the United States. The AKP faces no bottom-up pressure to tone down anti-Western language and little backlash from voters over the breakdown of the EU accession process. The same is true about the deterioration of relations with Washington, Turkey’s most important ally, but also the main backer of Syrian Kurds, whom Ankara has deemed an imminent threat. And yet, the Turkish economy is heavily integrated with the European Union economy and Ankara benefits from the EU accession process. Ankara cannot risk a serious break with Europe, lest otherwise risking undermining the economy, an outcome that would consequently undercut political support. The reality is that the desire of Turkish political leaders to sustain and maximize economic growth offers the only leverageable factor available to the EU and to US leaders concerned with Ankara’s drift. Yet employing that leverage would be incongruent with the ethos of the transatlantic alliance and would not be seen by key actors as an attractive policy tool.

Notes

1 “Erdogan Says Europe Aiding Terrorism with Support for Kurdish Militants,” Reuters, November 6, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-kurds-erdogan/erdogan-says-europe-aiding-terrorism-with-support-for-kurdish-militants-idUSKBN1310NW.

2 Esther King, “Germany Investigates Imams over Alleged Spying for Turkey: Report,” Politico, February 15, 2017 https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-investigates-imams-over-allegedspying-for-turkey-report/.

3 According to Metropoll, the survey was carried out using stratified sampling and weighting methods on 1,961 people in 28 provinces based on the 26 regions of Turkey’s NUTS 2 system between January 13 and 19, 2018. The survey used face-to-face questioning with a margin error of 2.21 percent at a 95 percent level of confidence.

4 John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/turkey-experiencingnew- nationalism/.

5 Ibid; See also: Jacob Poushter, The Turkish people don’t look favorably upon the U.S., or any other country, really, Pew Research Center, October 31, 2014, http://www.pewresearch.org/ fact-tank/2014/10/31/the-turkish-people-dont-look-favorablyupon- the-u-s-or-any-other-country-really/.

6 Ralph Boulton, Ece Toksabay, Andrea Shalal, “Turkey’s Erdogan Compares German Behavior with Nazi Period,” Reuters, March 5, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-referendumgermany/ turkeys-erdogan-compares-german-behavior-withnazi- period-idUSKBN16C0KD; Kareem Shaheen,“‘Assault on Freedom of Expression’: Die Welt journalist’s Arrest in Turkey Condemned,” The Guardian, February 28, 2017, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/28/formal-arrest-of-die-weltjournalist- deniz-yucel-in-turkey-condemned-german.

7 “Dutch police expel Turkish minister as ‘Nazi remnants’ row escalates,” The Guardian, March 11, 2017, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/11/erdogan-brands-dutch-naziremnants- for-barring-turkish-mp; “Dutch government formally withdraws Turkish ambassador over 2017 row,” Reuters, February 5, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-netherlands-turkeydiplomacy/ dutch-government-formally-withdraws-turkishambassador- over-2017-row-idUSKBN1FP1C5.

8 Menelaos Hadjicostis, “Eni executive: drilling off Cyprus could be put on hold,” Washington Post, February 22, 2018, https://www. washingtonpost.com/business/turkey-says-wont-allow-onesided- gas-search-off-cyprus/2018/02/22/7ff9ac40-17e8-11e8- 930c-45838ad0d77a_story.html.

9 Rod Nordland, “Czechs Release Top Kurdish Official Despite Turkish Extradition Request,” The New York Times, February 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/27/world/middleeast/ turkey-syria-kurds.html.

10 “The Latest: Greece says Turkish coast guard rams Greek boat,” NY Daily News, February 13, 2018, http://www.nydailynews.com/ newswires/news/business/latest-greece-turkish-coast-guardrams- greek-boat-article-1.3817256; “Turkey arrests Greek soldiers on espionage charges,” Deutsche Welle, March 2, 2018, http:// www.dw.com/en/turkey-arrests-greek-soldiers-on-espionagecharges/ a-42804765.

11 Aaron Stein, Turkey: Managing Tensions and Options to Engage, Atlantic Council, November 2, 2017, http://www.atlanticcouncil. org/publications/issue-briefs/turkey-managing-tensions-andoptions- to-engage.

12 “Erdogan: NATO must resist U.S. Syria plan,” Daily Star, January 17, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2018/ Jan-17/434074-erdogan-nato-must-resist-us-syria-plan.ashx.

13 This finding, however, is incongruent with the Center for American Progress’ survey results, where only 24 percent of respondents had a favorable view toward NATO. The difference, it appears, stems from how the question was phrased, and may indicate that while Turkish citizens may not have favorable views of NATO, respondents still understand that a collective security guarantee is important for Turkish security. See: John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www. americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/ turkey-experiencing-new-nationalism/.

14 John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/turkey-experiencingnew- nationalism/.

15 Sinan Ulgen, Trade as Turkey’s EU Anchor, Carnegie Europe, December 13, 2017, http://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/12/13/tradeas- turkey-s-eu-anchor-pub-75002.

16 Celal Ozcan, “Merkel conveys Germany’s veto on Customs Union update with Turkey to Juncker,” Hurriyet Daily News, August 31, 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/merkel-conveys-germanys-vetoon- customs-union-update-with-turkey-to-juncker-117422.

17 “Journalist for German newspaper arrested in Turkey,” The Guardian, February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/ journalist-for-german-newspaper-arrested-in-turkey.

18 “Dutch-Turkey friendship group to be abolished,” Hurriyet Daily News, March 15, 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/dutchturkey- friendship-group-to-be-abolished-110830.

19 Tuvan Gumrukcu and Tulay Karadeniz, “Turkey targets Dutch with diplomatic sanctions as ‘Nazi’ row escalates,” Reuters, March 12, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-referendumnetherlands/ turkey-targets-dutch-with-diplomatic-sanctions-asnazi- row-escalates-idUSKBN16J0IU.

20 Orhan Coskun, “Turkey reassures investors, says Dutch business not at risk,” Reuters, March 15, 2017, https://www.reuters. com/article/us-turkey-referendum-netherlands-ministe/ turkey-reassures-investors-says-dutch-business-not-at-riskidUSKBN16M0OT.

21 Sevil Erkus, “Turkey offers to take lead in NATO’s rapid reaction forces,” Hurriyet Daily News, May 20, 2015, http://www. hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-offers-to-take-lead-in-natos-rapidreaction- forces--82662.

22 Turkey’s Pulse: Operation Olive Branch in the Eyes of the Voters, Metropoll, February 2018.

23 Ibid.

24 “Izmir’de Teror Saldirisi,” Milliyet, January 5, 2017, http://www. milliyet.com.tr/izmir-de-teror-saldirisi-izmir-yerelhaber-1759270/.

25 “Blast in Turkish capital was bomb, eight detained: governor’s office,” Reuters, February 2, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-turkey-blast/blast-in-turkish-capital-was-bomb-eightdetained-governors-office-idUSKBN1FM29I.

26 Turkey’s PKK Conflict: The Rising Toll, International Crisis Group, last updated February 2018, http://www.crisisgroup.be/ interactives/turkey/.

27 Onur Ant and Asli Kandemir, “Turkey Reassessing Scope of Stimulus Program, Erdogan Aide Says,” Bloomberg, February 8, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-08/ turkey-reassessing-scope-of-stimulus-program-erdogan-aide-says

28 “Rating Action: Moody’s downgrades Turkey’s sovereign ratings to Ba2 from Ba1; outlook changed to stable from negative,” Moody’s Investor Services, March 7, 2018, https://www.moodys. com/research/Moodys-downgrades-Turkeys-sovereign-ratingsto-Ba2-from-Ba1-outlook--PR_379438.

29 “IMF warns about overheating in Turkey’s economy,” Hurriyet Daily News, February 20, 2018, http://www.hurriyetdailynews. com/imf-warns-about-overheating-in-turkeys-economy-127608.

30 “Merkel attacks Turkey’s ‘misuse’ of Interpol warrants,” Reuters, August 20, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-turkeyelection/merkel-attacks-turkeys-misuse-of-interpol-warrantsidUSKCN1B00IP; “Turkey is trying to extradite its political opponents from Europe,” The Economist, August 22, 2017, https:// www.economist.com/news/europe/21726993-arresting-turkishgerman-writer-spain-risks-doing-recep-tayyip-erdogans-dirtywork-turkey.

31 Kate Connolly, “Merkel wins CDU party’s backing for German coalition deal,” The Guardian, February 26, 2018, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/26/angela-merkel-cdu-tovote-on-german-coalition-deal.

32 “Macron suggests ‘partnership’ with EU for Turkey, not membership,” France 24, January 5, 2018, http://www.france24. com/en/20180105-french-president-macron-suggestspartnership-deal-turkey-eu-not-membership-erdogan.

33 “January 5, 2018, ”Turkey, Germany vow to improve strained ties following Merkel-Yildirim meeting,” Hurriyet Daily News, February 15, 2018, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-germanyvow-to-improve-strained-ties-127409.

34 “Turkey, Russia, Iran FMs to assess Astana Syria process,” Anadolu Agency, March 6, 2018, https://aa.com.tr/en/ middle-east/turkey-russia-iran-fms-to-assess-astana-syriaprocess/1080894.

35 For an example of US-Turkish counter-terrorism cooperation, see: Craig Whitlock, “U.S. military drone surveillance is expanding to hot spots beyond declared combat zones,” Washington Post, July 20, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost. com/world/national-security/us-military-drone-surveillanceis-expanding-to-hot-spots-beyond-declared-combatzones/2013/07/20/0a57fbda-ef1c-11e2-8163--2c7021381a75_story. html?utm_term=.5bc0e123249c.

36 “Russia plans to sign contract to deliver second batch of S-400 systems to Turkey — source,” TASS Russian News Agency, February 14, 2018, http://tass.com/defense/989931.

About the Author

Aaron Stein is a resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

To address Turkish economic concerns, the AKP has pursued a series of stimulus measures to increase the gross domestic product. The initial catalyst for Turkish action came just after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, amid broader concerns about whether the fall-out would negatively impact economic growth.27 The stimulus has helped grow the economy, but Turkey’s current account deficit has grown considerably, and inflation has remained in the low double digits. These factors prompted the International Monetary Fund, in February 2018, to warn that the economy may be overheating and then for international ratings agency Moody’s to downgrade Turkey’s sovereign debt rating.28 The challenge for the AKP will be how to take steps to “cool off” the economy, without crossing Erdogan’s demands for high growth rates and low interest rates.29

The economic data, mixed with public anxiety about the economy, suggest that the AKP-MHP government will focus considerable attention on ensuring continued economic growth. The second most salient issue for voters, terrorism (and security in general) will also impact Turkish foreign policy.

In Syria, the events of the past two years underscore Ankara’s commitment to use military force—and to work with both Russia and Iran—to facilitate cross-border military operations to combat Kurdish-led militias. The Turkish government has also accused Europe (and the United States) of being soft on terror and has adopted tactics that inflame tensions with much of Europe. Ankara has flooded Interpol with red notices, a tactic that has increased tensions with different European countries over concerns that the system is being abused.30

The Interpol notices have primarily focused on Kurdish individuals with links to the PKK (albeit without any definitive connection to insurgent attacks), followers of the Fethullah Gulen movement, and Turkish dissidents in Europe. In every reported instance, the prospect of extradition to Turkey is remote—if not impossible—and the accused is released. The releases, in turn, prompt Turkish backlash, which further fuels bilateral tensions between Turkey and different European countries. The tensions do not undermine AKP support with the Turkish public, and instead help to reinforce deeply ingrained views about Turkey’s relationship with allies.

Ankara’s actions may be dismissed as an aberration, or a byproduct of Erdogan’s singular push to consolidate his authority at all costs. To do so, Erdogan faces no serious political repercussions for criticizing the West and for hyping up the terror issue, so long as the voters’ most pressing concern, the economy, is well managed. This dichotomy helps to explain Turkish policy making—and where Ankara may be vulnerable to external coercion. Russia, for example, used economic sanctions following the Turkish downing of an SU 24 bomber in November 2015 to compel a change in Turkish policy in Syria. Russia also had the advantage of being able to offer Ankara something that it wanted: a relatively free hand to launch a cross border operation against Kurdish majority forces in Syria.

The German government, too, used economic coercion to force changes to Turkish policy, culminating in a rumored political agreement to release German nationals held in Turkey without serious evidence in exchange for defense, trade, and political concessions. The German-Turkish bilateral relationship remains far from “normal,” however, after the federal election in September 2017 resulted in a coalition between the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).31

The two parties are against Turkish membership in the European Union. French President Emmanuel Macron has adopted a similar policy, telling reporters at a joint press conference with Erdogan that Turkey should not be an EU member, but instead should have a “partnership” with the bloc.32

The moribund accession process is not a salient issue for Turkish voters. However, the continued German veto of further discussions with Turkey on an updated customs union, while far from an animating factor amongst the Turkish public, could negatively impact the Turkish economy. As a result, Ankara has both economic and political incentives to negotiate with Europe and to try to “reset” relations with Germany, following German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s pre-election announcement of a veto.33

This push-and-pull of the politically easy EU critiques typical in Turkey could undermine more important, longer-term policy issues, which would impact the issue voters most care about: the Turkish economy. The divergent, short-term instincts to bash outsiders versus the longer-term repercussions of Ankara’s aggressive rhetoric and actions explain Ankara’s rapid shifts in policy. For eight months in 2017, for example, Erdogan accused the German government of “actions no different to those of the Nazi period,” followed by an intimate foreign minister sit-down in Antalya to improve ties and to negotiate the release of an imprisoned German journalist, Deniz Yucel.

Implications for the United States: A New Relationship

The rapid changes in policy suggest a policy-making process in Turkey that is adrift and reactive to external events, but ultimately moored in economic and security self-interests. Ankara, for example, was able to overcome its difficulties with Russia to take action in Syria, in order to protect Turkey from a self-identified security threat in Syria.34

The Turkish government pursued a similar policy vis-à-vis Germany, wherein it continually has tried to balance between its narrow, populist political incentives to demonize the West while also managing to maintain functional economic relations. There are electoral reasons for this policy; however, the broader takeaway is that Ankara has settled on a policy of transactionalism with its allies and partners.

For the United States, the decrease in importance of the EU accession process deprives Washington of leverage to work to compel political change in Turkey. Specifically, the United States used to have a free ride on the European Union, particularly on addressing human rights-related issues, while at the same time working with Ankara on counter-terrorism-related issues.35

More recently, the twin collapses of the European Union process and the divergence in shared focus on US-Turkish counter-terrorism interests have undermined two key pillars of the relationship. Moreover, Ankara’s new transactional approach to foreign policy has led to a deepening of Turkish-Russian relations inside Syria and on defense procurement. In the case of the latter, Ankara’s purchase of Russian surface-to-air missiles36

risks undermining US-Turkish defense cooperation and eroding transatlantic trust in Turkey’s commitment to NATO. Yet, despite Alliance-wide dissatisfaction with the purchases and repeated warnings about the consequences, the Turkish government made the decision to go ahead with the purchase.

The polling data indicate that a narrow plurality (percentage) of AKP-MHP voters do not believe that NATO is beneficial for Turkish security. However, the number of voters that do believe the Alliance is important for Turkey is above 40 percent in both parties and, amongst all voters, just under 50 percent. In general, Turks do not have a favorable view of NATO, and so there is yet another divergence in political incentives that helps explain government rhetoric. At times of tension, the Turkish government faces few repercussions from voters when it challenges NATO. Yet, at the same time, Ankara’s day-to-day functions within the Alliance are insulated from much of this political rhetoric. Thus, the Turkish government faces few actual repercussions within the Alliance for its rhetoric, even though it may contribute to the broader Turkish distrust of the institution.

Conclusion: Coming to Terms with the New Turkey

The public opinion data cited in this paper represents a snapshot of Turkish public opinion. The findings help shed light on the internal, politically-driven aspects of Turkish policy making. The bigger question is whether the Turkish public’s unfavorable views of NATO will erode public perceptions about the Alliance’s value for security. Moreover, it is unclear if the constant negative reports about the United States and the Turkish government’s pervasive use of anti-American conspiracy theories to whip up populist support will have a spill-over effect and erode Turkish trust in supranational institutions, like NATO.

This report’s findings suggest that the most salient issue for Turkish policy makers in the near-to-medium term will be competent economic stewardship. Turkish distrust of outsiders provides policy makers with a low-risk, high-return incentive to blame Western countries and institutions for internal Turkish problems. The outcome, it appears, is that the Turkish government is comfortable with a policy of transactionalism with its traditional allies, even if those same allies have not yet come to terms with the fact that this is how the Turkish government now operates. The polling—and a long track-record of statements in power—clearly suggests that Ankara should not be expected to tout the benefits of its alliances and European allies.

The data suggest that the political incentives driving the current status quo remain in place, which is an outcome that should challenge long-held assumptions about the nature of Turkey’s relationship with Europe and, ultimately, the United States. The AKP faces no bottom-up pressure to tone down anti-Western language and little backlash from voters over the breakdown of the EU accession process. The same is true about the deterioration of relations with Washington, Turkey’s most important ally, but also the main backer of Syrian Kurds, whom Ankara has deemed an imminent threat. And yet, the Turkish economy is heavily integrated with the European Union economy and Ankara benefits from the EU accession process. Ankara cannot risk a serious break with Europe, lest otherwise risking undermining the economy, an outcome that would consequently undercut political support. The reality is that the desire of Turkish political leaders to sustain and maximize economic growth offers the only leverageable factor available to the EU and to US leaders concerned with Ankara’s drift. Yet employing that leverage would be incongruent with the ethos of the transatlantic alliance and would not be seen by key actors as an attractive policy tool.

Notes

1 “Erdogan Says Europe Aiding Terrorism with Support for Kurdish Militants,” Reuters, November 6, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-kurds-erdogan/erdogan-says-europe-aiding-terrorism-with-support-for-kurdish-militants-idUSKBN1310NW.

2 Esther King, “Germany Investigates Imams over Alleged Spying for Turkey: Report,” Politico, February 15, 2017 https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-investigates-imams-over-allegedspying-for-turkey-report/.

3 According to Metropoll, the survey was carried out using stratified sampling and weighting methods on 1,961 people in 28 provinces based on the 26 regions of Turkey’s NUTS 2 system between January 13 and 19, 2018. The survey used face-to-face questioning with a margin error of 2.21 percent at a 95 percent level of confidence.

4 John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/turkey-experiencingnew- nationalism/.

5 Ibid; See also: Jacob Poushter, The Turkish people don’t look favorably upon the U.S., or any other country, really, Pew Research Center, October 31, 2014, http://www.pewresearch.org/ fact-tank/2014/10/31/the-turkish-people-dont-look-favorablyupon- the-u-s-or-any-other-country-really/.

6 Ralph Boulton, Ece Toksabay, Andrea Shalal, “Turkey’s Erdogan Compares German Behavior with Nazi Period,” Reuters, March 5, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-referendumgermany/ turkeys-erdogan-compares-german-behavior-withnazi- period-idUSKBN16C0KD; Kareem Shaheen,“‘Assault on Freedom of Expression’: Die Welt journalist’s Arrest in Turkey Condemned,” The Guardian, February 28, 2017, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/28/formal-arrest-of-die-weltjournalist- deniz-yucel-in-turkey-condemned-german.

7 “Dutch police expel Turkish minister as ‘Nazi remnants’ row escalates,” The Guardian, March 11, 2017, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/11/erdogan-brands-dutch-naziremnants- for-barring-turkish-mp; “Dutch government formally withdraws Turkish ambassador over 2017 row,” Reuters, February 5, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-netherlands-turkeydiplomacy/ dutch-government-formally-withdraws-turkishambassador- over-2017-row-idUSKBN1FP1C5.

8 Menelaos Hadjicostis, “Eni executive: drilling off Cyprus could be put on hold,” Washington Post, February 22, 2018, https://www. washingtonpost.com/business/turkey-says-wont-allow-onesided- gas-search-off-cyprus/2018/02/22/7ff9ac40-17e8-11e8- 930c-45838ad0d77a_story.html.

9 Rod Nordland, “Czechs Release Top Kurdish Official Despite Turkish Extradition Request,” The New York Times, February 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/27/world/middleeast/ turkey-syria-kurds.html.

10 “The Latest: Greece says Turkish coast guard rams Greek boat,” NY Daily News, February 13, 2018, http://www.nydailynews.com/ newswires/news/business/latest-greece-turkish-coast-guardrams- greek-boat-article-1.3817256; “Turkey arrests Greek soldiers on espionage charges,” Deutsche Welle, March 2, 2018, http:// www.dw.com/en/turkey-arrests-greek-soldiers-on-espionagecharges/ a-42804765.

11 Aaron Stein, Turkey: Managing Tensions and Options to Engage, Atlantic Council, November 2, 2017, http://www.atlanticcouncil. org/publications/issue-briefs/turkey-managing-tensions-andoptions- to-engage.

12 “Erdogan: NATO must resist U.S. Syria plan,” Daily Star, January 17, 2018, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2018/ Jan-17/434074-erdogan-nato-must-resist-us-syria-plan.ashx.

13 This finding, however, is incongruent with the Center for American Progress’ survey results, where only 24 percent of respondents had a favorable view toward NATO. The difference, it appears, stems from how the question was phrased, and may indicate that while Turkish citizens may not have favorable views of NATO, respondents still understand that a collective security guarantee is important for Turkish security. See: John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www. americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/ turkey-experiencing-new-nationalism/.

14 John Halpin, Michael Werz, Alan Makovsky, and Max Hoffman, Is Turkey Experiencing a New Nationalism?, Center for American Progress, February 11, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/security/reports/2018/02/11/445620/turkey-experiencingnew- nationalism/.

15 Sinan Ulgen, Trade as Turkey’s EU Anchor, Carnegie Europe, December 13, 2017, http://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/12/13/tradeas- turkey-s-eu-anchor-pub-75002.

16 Celal Ozcan, “Merkel conveys Germany’s veto on Customs Union update with Turkey to Juncker,” Hurriyet Daily News, August 31, 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/merkel-conveys-germanys-vetoon- customs-union-update-with-turkey-to-juncker-117422.

17 “Journalist for German newspaper arrested in Turkey,” The Guardian, February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/ journalist-for-german-newspaper-arrested-in-turkey.

18 “Dutch-Turkey friendship group to be abolished,” Hurriyet Daily News, March 15, 2017, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/dutchturkey- friendship-group-to-be-abolished-110830.

19 Tuvan Gumrukcu and Tulay Karadeniz, “Turkey targets Dutch with diplomatic sanctions as ‘Nazi’ row escalates,” Reuters, March 12, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-referendumnetherlands/ turkey-targets-dutch-with-diplomatic-sanctions-asnazi- row-escalates-idUSKBN16J0IU.

20 Orhan Coskun, “Turkey reassures investors, says Dutch business not at risk,” Reuters, March 15, 2017, https://www.reuters. com/article/us-turkey-referendum-netherlands-ministe/ turkey-reassures-investors-says-dutch-business-not-at-riskidUSKBN16M0OT.

21 Sevil Erkus, “Turkey offers to take lead in NATO’s rapid reaction forces,” Hurriyet Daily News, May 20, 2015, http://www. hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-offers-to-take-lead-in-natos-rapidreaction- forces--82662.

22 Turkey’s Pulse: Operation Olive Branch in the Eyes of the Voters, Metropoll, February 2018.

23 Ibid.

24 “Izmir’de Teror Saldirisi,” Milliyet, January 5, 2017, http://www. milliyet.com.tr/izmir-de-teror-saldirisi-izmir-yerelhaber-1759270/.

25 “Blast in Turkish capital was bomb, eight detained: governor’s office,” Reuters, February 2, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-turkey-blast/blast-in-turkish-capital-was-bomb-eightdetained-governors-office-idUSKBN1FM29I.

26 Turkey’s PKK Conflict: The Rising Toll, International Crisis Group, last updated February 2018, http://www.crisisgroup.be/ interactives/turkey/.

27 Onur Ant and Asli Kandemir, “Turkey Reassessing Scope of Stimulus Program, Erdogan Aide Says,” Bloomberg, February 8, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-08/ turkey-reassessing-scope-of-stimulus-program-erdogan-aide-says

28 “Rating Action: Moody’s downgrades Turkey’s sovereign ratings to Ba2 from Ba1; outlook changed to stable from negative,” Moody’s Investor Services, March 7, 2018, https://www.moodys. com/research/Moodys-downgrades-Turkeys-sovereign-ratingsto-Ba2-from-Ba1-outlook--PR_379438.

29 “IMF warns about overheating in Turkey’s economy,” Hurriyet Daily News, February 20, 2018, http://www.hurriyetdailynews. com/imf-warns-about-overheating-in-turkeys-economy-127608.

30 “Merkel attacks Turkey’s ‘misuse’ of Interpol warrants,” Reuters, August 20, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-turkeyelection/merkel-attacks-turkeys-misuse-of-interpol-warrantsidUSKCN1B00IP; “Turkey is trying to extradite its political opponents from Europe,” The Economist, August 22, 2017, https:// www.economist.com/news/europe/21726993-arresting-turkishgerman-writer-spain-risks-doing-recep-tayyip-erdogans-dirtywork-turkey.

31 Kate Connolly, “Merkel wins CDU party’s backing for German coalition deal,” The Guardian, February 26, 2018, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/26/angela-merkel-cdu-tovote-on-german-coalition-deal.

32 “Macron suggests ‘partnership’ with EU for Turkey, not membership,” France 24, January 5, 2018, http://www.france24. com/en/20180105-french-president-macron-suggestspartnership-deal-turkey-eu-not-membership-erdogan.

33 “January 5, 2018, ”Turkey, Germany vow to improve strained ties following Merkel-Yildirim meeting,” Hurriyet Daily News, February 15, 2018, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-germanyvow-to-improve-strained-ties-127409.

34 “Turkey, Russia, Iran FMs to assess Astana Syria process,” Anadolu Agency, March 6, 2018, https://aa.com.tr/en/ middle-east/turkey-russia-iran-fms-to-assess-astana-syriaprocess/1080894.

35 For an example of US-Turkish counter-terrorism cooperation, see: Craig Whitlock, “U.S. military drone surveillance is expanding to hot spots beyond declared combat zones,” Washington Post, July 20, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost. com/world/national-security/us-military-drone-surveillanceis-expanding-to-hot-spots-beyond-declared-combatzones/2013/07/20/0a57fbda-ef1c-11e2-8163--2c7021381a75_story. html?utm_term=.5bc0e123249c.

36 “Russia plans to sign contract to deliver second batch of S-400 systems to Turkey — source,” TASS Russian News Agency, February 14, 2018, http://tass.com/defense/989931.

About the Author

Aaron Stein is a resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

No comments:

Post a Comment