The Western alliance is in trouble

That should worry Europe, America and the world

AMERICA did as much as any country to create post-war Europe. In the late 1940s and the 1950s it was midwife to the treaty that became the European Union and to NATO, the military alliance that won the cold war. The United States acted partly out of charity, but chiefly out of self-interest. Having been dragged into two world wars, it wanted to banish Franco-German rivalry and build a rampart against the Soviet threat. After the Soviet collapse in 1991, the alliance anchored democracy in the newly liberated states of eastern Europe.

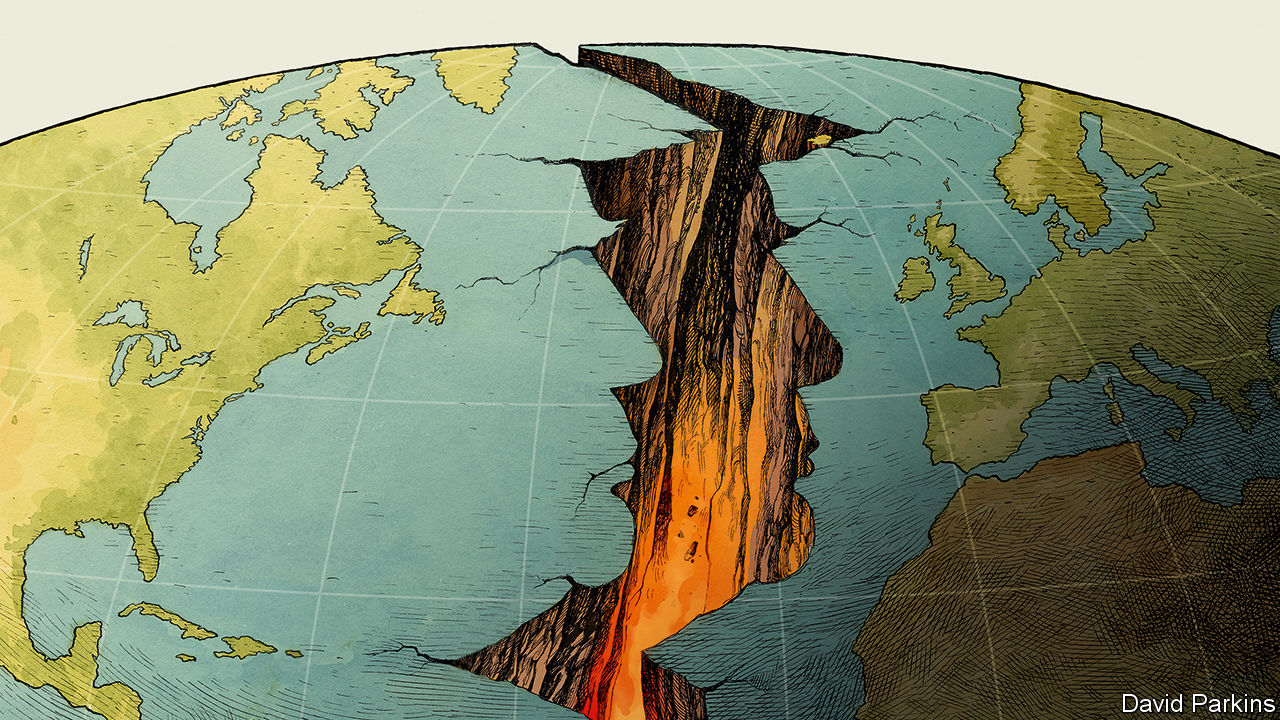

Today, however, America and Europe are separated by a growing rift. The mood before the NATO summit in Brussels on July 11th and 12th is poisonous. As President Donald Trump accuses the Europeans of bad faith and of failing to pull their weight, they accuse him of crass vandalism. A second summit, between Vladimir Putin and Mr Trump in Helsinki on July 16th, could produce the once-unthinkable spectacle of an American president treating his Russian opponent better than he has just treated his allies.

Even if the two summits pass off without controversy—as they might, given how Mr Trump delights in confounding his critics—the differing priorities, divergent beliefs and clashing political cultures will remain. The Western alliance is in trouble, and that should worry Europe, America and the world.

Every alliance has its tensions, but the Western one is strained on a bewildering number of fronts (see article). Mr Trump, and his generals, are exasperated by the feeble efforts of many NATO members to honour their promise to raise defence spending towards 2% of GDP by 2024. The American right tends to condemn European support for the Iranian nuclear deal (which Mr Trump quit), and what it sees as a bias against Israel. And policymakers from both parties think that, as the world’s attention shifts to Asia, whining, sanctimonious Europeans deserve less of their time.

As if that were not enough, Mr Trump fatuously accuses the EU of being “set up to take advantage of the United States” and chastises it for unfair trade. Meanwhile, Europe is divided. Italy has a new populist coalition that is pro-Putin. So, increasingly, is Turkey, a member of NATO (but not the EU) which is hostile to the liberal democratic values that bind the alliance. Worse could be in store. A Labour government in Britain under Jeremy Corbyn, who has a long history of opposing the use of arms by the West, would treat America with deep suspicion; he could even try to leave NATO.

The first step is not to make the job harder. Europe should do everything it can to resist Mr Trump’s instinct to lump trade with security. Wrapping them up together will only make the West less secure as well as poorer.

Next, supporters of the alliance need to be practical. That means paying up. Mr Trump is right to complain about countries like Germany and Italy, which spent just 1.22% and 1.13% of GDP on defence in 2017. Indeed, he could go further. Too little of defence spending is useful—over a third of Belgium’s is eaten up by pensions. More should go on R&D and equipment.

For America’s allies, being practical also means keeping up. Collaboration in areas like cyber-security will make the alliance more valuable to America. More urgently NATO must continue to sharpen its response to the tactics of misinformation and infiltration that Russia used in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Politics waxes and wanes. Lost military understanding is hard to rebuild. Exercises that cement NATO’s remarkably close working military relations are more vital than ever.

And being practical means sticking together. Negotiating over Brexit, the EU is minded to shut Britain out of the union’s security structures because it will no longer be a member. Given Britain’s military experience, its arms industry and its intelligence agencies, that is self-defeating. Instead, the EU’s members should seek to bind Britain in by, for example, promoting the European Intervention Initiative, proposed by France, which aims to create a force that can act in crises. Once America would have seen such a plan as a threat to NATO. Today it would stand both as insurance and as a sign that Europe is willing to take on more responsibility.

The need for security remains. Russia is not the Soviet Union but, as a declining power, it feels threatened. It has modernised its forces and is prepared to deploy them. The need to anchor European democracy remains, too. As authoritarianism creeps up on Poland and Hungary, the EU and NATO can once again help limit its advance. And there is the extra benefit of how Europe helps America project power, by providing bases, troops and, usually, diplomatic support.

NATO is more fragile than Mr Trump thinks. At its core is the pledge to treat an attack on one member in the North Atlantic region as an attack on them all. His vacillation and his hostility to Europe weakens that promise, if only because it reveals his scorn for the idea that small countries have the same rights as big ones. Asia is watching, as is Mr Putin. The more Mr Trump bullies his allies, the more the world will doubt America’s security guarantees. Because great powers compete in a grey zone between peace and war, that risks miscalculation.

Mr Trump believes he is a master negotiator in pursuit of a stronger America. With Europe, as with so much else, he gravely undervalues what he is giving up.

Today, however, America and Europe are separated by a growing rift. The mood before the NATO summit in Brussels on July 11th and 12th is poisonous. As President Donald Trump accuses the Europeans of bad faith and of failing to pull their weight, they accuse him of crass vandalism. A second summit, between Vladimir Putin and Mr Trump in Helsinki on July 16th, could produce the once-unthinkable spectacle of an American president treating his Russian opponent better than he has just treated his allies.

Every alliance has its tensions, but the Western one is strained on a bewildering number of fronts (see article). Mr Trump, and his generals, are exasperated by the feeble efforts of many NATO members to honour their promise to raise defence spending towards 2% of GDP by 2024. The American right tends to condemn European support for the Iranian nuclear deal (which Mr Trump quit), and what it sees as a bias against Israel. And policymakers from both parties think that, as the world’s attention shifts to Asia, whining, sanctimonious Europeans deserve less of their time.

As if that were not enough, Mr Trump fatuously accuses the EU of being “set up to take advantage of the United States” and chastises it for unfair trade. Meanwhile, Europe is divided. Italy has a new populist coalition that is pro-Putin. So, increasingly, is Turkey, a member of NATO (but not the EU) which is hostile to the liberal democratic values that bind the alliance. Worse could be in store. A Labour government in Britain under Jeremy Corbyn, who has a long history of opposing the use of arms by the West, would treat America with deep suspicion; he could even try to leave NATO.

SACEUR punch

This newspaper believes that the Western alliance is worth saving. In a dangerous and increasingly authoritarian world, it can act as a vital source of security and a bastion of democracy. But the alliance does not have a God-given right to survive. It must continually earn its place. The question is: how?The first step is not to make the job harder. Europe should do everything it can to resist Mr Trump’s instinct to lump trade with security. Wrapping them up together will only make the West less secure as well as poorer.

Next, supporters of the alliance need to be practical. That means paying up. Mr Trump is right to complain about countries like Germany and Italy, which spent just 1.22% and 1.13% of GDP on defence in 2017. Indeed, he could go further. Too little of defence spending is useful—over a third of Belgium’s is eaten up by pensions. More should go on R&D and equipment.

For America’s allies, being practical also means keeping up. Collaboration in areas like cyber-security will make the alliance more valuable to America. More urgently NATO must continue to sharpen its response to the tactics of misinformation and infiltration that Russia used in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Politics waxes and wanes. Lost military understanding is hard to rebuild. Exercises that cement NATO’s remarkably close working military relations are more vital than ever.

And being practical means sticking together. Negotiating over Brexit, the EU is minded to shut Britain out of the union’s security structures because it will no longer be a member. Given Britain’s military experience, its arms industry and its intelligence agencies, that is self-defeating. Instead, the EU’s members should seek to bind Britain in by, for example, promoting the European Intervention Initiative, proposed by France, which aims to create a force that can act in crises. Once America would have seen such a plan as a threat to NATO. Today it would stand both as insurance and as a sign that Europe is willing to take on more responsibility.

Fighting for the mind

Last is the battle of ideas. If NATO and the EU did not already exist, they would not be created. Since the Soviet collapse, the sense of threat has receded and the barriers to working together have risen. Yet that does not make the transatlantic alliance “obsolete”, as Mr Trump once claimed. America’s alliances are an asset that are the envy of Russia and China. NATO is an inheritance that is all the more precious for being irreplaceable.The need for security remains. Russia is not the Soviet Union but, as a declining power, it feels threatened. It has modernised its forces and is prepared to deploy them. The need to anchor European democracy remains, too. As authoritarianism creeps up on Poland and Hungary, the EU and NATO can once again help limit its advance. And there is the extra benefit of how Europe helps America project power, by providing bases, troops and, usually, diplomatic support.

NATO is more fragile than Mr Trump thinks. At its core is the pledge to treat an attack on one member in the North Atlantic region as an attack on them all. His vacillation and his hostility to Europe weakens that promise, if only because it reveals his scorn for the idea that small countries have the same rights as big ones. Asia is watching, as is Mr Putin. The more Mr Trump bullies his allies, the more the world will doubt America’s security guarantees. Because great powers compete in a grey zone between peace and war, that risks miscalculation.

Mr Trump believes he is a master negotiator in pursuit of a stronger America. With Europe, as with so much else, he gravely undervalues what he is giving up.

No comments:

Post a Comment