Creating the conditions for a just peace in Ukraine.

An unprecedented feature of European solidarity during wartime. (See below for French translation.)

Disclaimer: all opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the author and not those of his employer.

"Europe will be forged in crises and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises", wrote Jean Monnet, one of the EU’s founding fathers in his memoirs first published in 1976. Jump forward to 24th of February 2022, the day on which Russia unleashed its war of aggression against, and Monnet’s words seem more pertinent than ever before

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine constitutes an undisputable, blatant violation of the United Nations Charter and international law as well as presenting a clear challenge to the EU’s fundamental values. It has forced millions of Ukrainians to flee the country and has led to countless war crimes being committed in and against Ukraine.

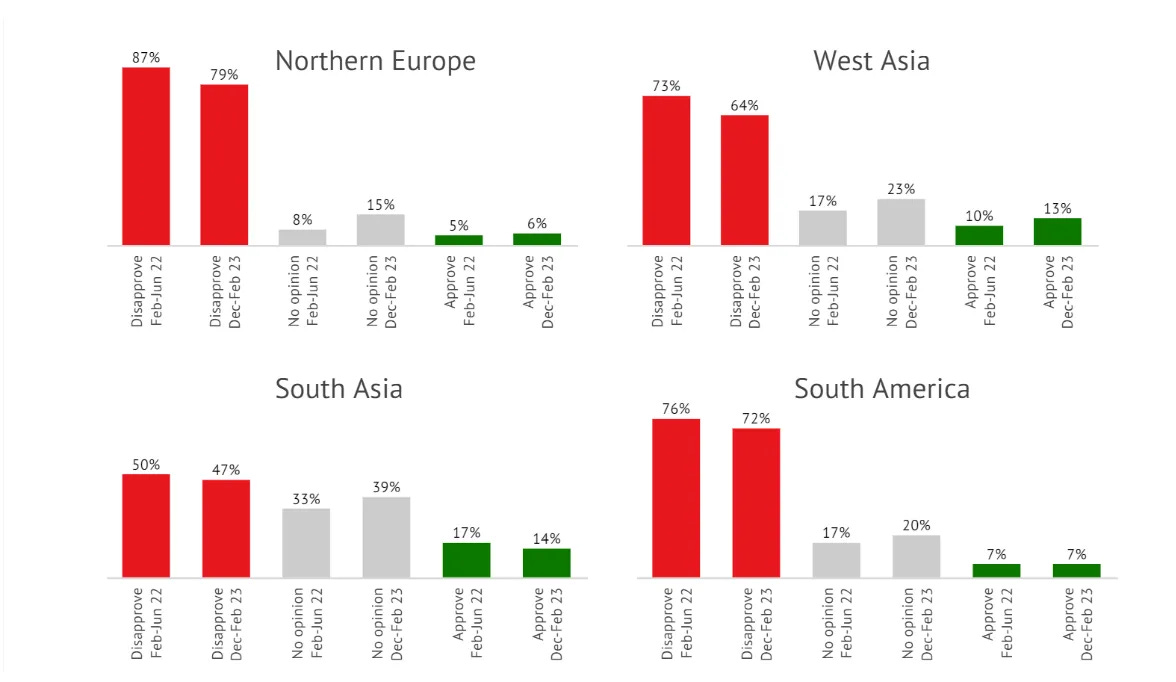

With the second anniversary of the war just around the corner, public opinion in some EU Members States has started to show worrying signs of ambivalence. The 24th of February 2024 may now be perceived as yet another day in a conflict that is increasingly being regarded as just one of many crises EU citizens face.

While it’s safe to assume that Monnet’s words won’t be on the mind of many EU citizens who are set to cast their vote in the European elections this summer, the message conveyed therein hopefully will. The EU was and will continue to be profoundly affected by the events in Ukraine. Since the first day of Russia’s invasion, the EU and its member states have come together and largely acted as a unified voice of support to Ukraine. With occasional cracks now appearing in this unified EU position, it is important to remind ourselves that the actions the EU and its Member States will (or will not) take are set to have a profound effect on both Ukraine, the EU and the European continent as a whole.

While much media attention has been devoted to the immediate military, macro-economic and humanitarian support provided by the EU and its Member States in wartime, another unprecedented feature of European solidarity with Ukraine has remained largely confined to the realm of academia and policy maker’s desks: the creation of conditions for a long-term ‘just peace’ in Ukraine.

What constitutes a ‘just peace’ for Ukraine?

The term ‘just peace’ has recently gained traction amongst commentators discussing the 10-point peace plan presented by President Zelenskyy last year.[1] In this plan, the restoration of justice sits prominently alongside other objectives that have recently gained substantial media traction such as the restoration of territorial integrity and the need for food security.

The reason for this is simple: without transitional justice (the way in which societies deal with legacies of systematic and serious human rights violations), there can be no long-term healing and reconciliation process in Ukrainian society. The concept of just peace, while too complex to further elaborate upon here at length, embodies a similar approach to post-war reconciliation: it encompasses ‘a process whereby peace and justice are reached together by two or more parties recognizing each other’s identities, each renouncing some central demands, and each accepting to abide by common rules jointly developed’.[2]

One of the key elements in transitionary justice is the need to provide redress to victims. The 10-point peace plan clearly illustrates that such an approach can take different forms, including redress through criminal justice but also through other justice measures, such as the payment of reparations. It calls for perpetrators of international crimes committed during this war to be held accountable, damages suffered by the victims of this war to be compensated and, by extension, impunity to be prevented.

The initial instinct might be to conclude that these efforts, while laudable, will only really become relevant once peace negotiations, and in extension an end to this war, have come in sight. However, this idea disregards the fact that the creation of conditions for a just peace, similar to other forms of wartime support, is highly time sensitive and subject to political momentum.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the first step in any process aimed at holding perpetrators of crimes accountable: the collection of evidence. Since the start of the war, over 124 000 incidents constituting alleged international crimes have been reported in Ukraine and 17 EU member states have opened national investigations into the crimes committed on Ukrainian territory. The testimonies and other forms of evidence which support these cases are essential preconditions for any future potential prosecution and thus need to be treated in a timely, careful fashion both inside and outside of Ukraine. This is all the more important as many types of evidence degrade with the passage of time.

On the ground, the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office (PGO) supported by international partners, including the Commission, has done a remarkable job of dealing with the huge caseload increase it has faced since the start of the war, providing witnesses with the support and protection they need. On the international level, the EU’s agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation, Eurojust, has played a key role in enhancing effective cooperation and coordination between the judicial authorities investigating the crimes committed during this war. It has done so, first of all, by the establishment of an International Crimes Evidence Database (CICED) which allows for the preserving, storing and analyzing of evidence of core international crimes collected by judicial authorities.

Furthermore, a number of countries have created a so-called Joint Investigation Team (JIT) for Ukraine, which has enabled participating countries to further coordinate their criminal investigations, supported by Eurojust. Most recently, the JIT members set up the International Centre for the Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression, a judicial body where independent prosecutors from different countries work together to exchange evidence and develop a common investigative and prosecution strategy, pending any final decisions on where specific cases of war crimes will, one day, be prosecuted.

Evidence will one day be produced in front of a court that will judge perpetrators for crimes committed during this war. A number of different actors will play a role in this process. First and foremost Ukraine’s national jurisdiction, where the majority of these crimes will have to be prosecuted. Secondly, the International Criminal Court will be able to prosecute for crimes for which it is competent. It has already started this work, notably by issuing an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin. Finally, there has been much discussion of a potential future special tribunal with the competence to prosecute the so-called ‘mother of all crimes’, the crime of aggression.

In a similar vein, any attempt at making sure Russia will pay for Ukraine’s reconstruction by paying reparations for the damage caused during this war relies on the ability to collect evidence of the damages inflicted upon Ukraine as well as figuring out next steps. The move by over 40 countries to recently join in the creation of a Register of Damage under the auspice of the Council of Europe is a notable step in the right direction. The Register, which the European Union joined as a Founding Associate Member, will serve as a ‘record of evidence and claims for damage, loss or injury caused to all natural and legal persons concerned, as well as to the State of Ukraine’ during this war. It will serve as the first step towards the creation of a fully-fledged compensation mechanism with an appropriate claims board and compensation fund.

The need to build on a strong track-record

In order to ensure a just peace for Ukraine, political commitment and perseverance will be needed in a time where support to Ukraine has become the subject of political debate in many capitals inside and outside of Europe.

With the war entering yet another unpredictable year, both on the battlefield and off it, the calls for a negotiated settlement to end this war will become ever stronger. In these negotiations, the issue of a just peace ought to play a key role. Russia is likely to oppose any attempts at ensuring accountability for the crimes committed during this war while Ukraine will feel the weight of a population that has suffered substantial harm. In anticipation of any such discussions, it is essential that Ukraine and its international partners continue to build on their strong track-record in preparing for a just peace in Ukraine.

As outlined briefly above, such an approach could include the setting-up of an international tribunal for the crime of aggression to fill existent legal gaps in the criminal justice system, as well as the deployment of a fully-fledged compensation mechanism through which Russia will pay for the damages caused during this war. On a more strategic level, future negotiators will be expected to resist any temptation to treat justice in a transactional fashion, as just one of many topics on the negotiation table. Rather, the creation of a just peace should continue to be one of the cornerstones of any sustainable, long-term EU strategy towards Ukraine. It is only by ensuring that justice is served, that the creation of a once again free and sovereign Ukrainian nation can be fully completed.

[1] https://www.president.gov.ua/storage/j-files-storage/01/19/53/32af8d644e6cae41791548fc82ae2d8e_1691483767.pdf

[2] Allan & Keller, What is a Just Peace? 2006). https://academic.oup.com/book/8594/chapter-abstract/154522302?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=true#no-access-message

No comments:

Post a Comment