QUINCY INSTİTUTE

What was Henry Kissinger's impact on U.S foreign policy?

Symposium: Peace or destruction — what was Kissinger's impact?

Wide range of experts and commentators weigh in on the conflicted legacy of an American statesman.

It speaks volumes that the death of Henry Kissinger, announced on Wednesday, drew major news obituaries that rivaled those of late American presidents' in length and depth. The news was met with equal parts of vitriol and paeans across social media, the former reflected in words like "war criminal" and "monster," the latter, "genius" and "master."

His intellectually-driven, hard-nosed statecraft and strategy has long been embraced by realists who appreciate Kissinger's rejection of ideological doctrine in favor of interest-driven realpolitik. They credit him with détente and managing the Soviet threat in the Cold War. His critics say his approach was responsible for government-led massacres in developing nations and Washington's scorched earth policies in Indochina. Humanity suffered while the "great game" was played, no matter how well, from the Nixon White House and in later presidencies (12 total) for which Kissinger advised.

But was his impact on U.S. foreign policy ultimately positive or negative? We asked a wide range of historians, former diplomats, journalists and scholars to pick one and defend it.

Andrew Bacevich, George Beebe, Tom Blanton, Michael Desch, Anton Fedyashin, Chas Freeman, John Allen Gay, David Hendrickson, Robert Hunter, Anatol Lieven, Stephen Miles, Tim Shorrock, Monica Duffy Toft, Stephen Walt

Andrew Bacevich, historian and co-founder of the Quincy Institute

I met Kissinger just once, at a small gathering in New York back in the 1990s. When the event adjourned, he walked over to where I was sitting and spoke to me. "Did you serve in the military?" "Yes," I said. "In Vietnam?" "Yes." His tone filled with sadness, he said: "We really wanted to win that one."

I did not reply but as he walked away, I thought: What an accomplished liar.

George Beebe, Director of Grand Strategy, Quincy Institute

Henry Kissinger’s impact on American foreign policy, although controversial, was on balance overwhelmingly positive. As he entered office in 1968, America was overextended abroad and beset by domestic political conflict. An increasingly powerful Soviet Union threatened to achieve superiority over America’s nuclear and conventional arsenals. The United States needed to extract itself from Vietnam and focus on domestic healing, yet any retreat into isolationism would allow Moscow a free hand to intimidate Western Europe and spread communism through the post-colonial world.

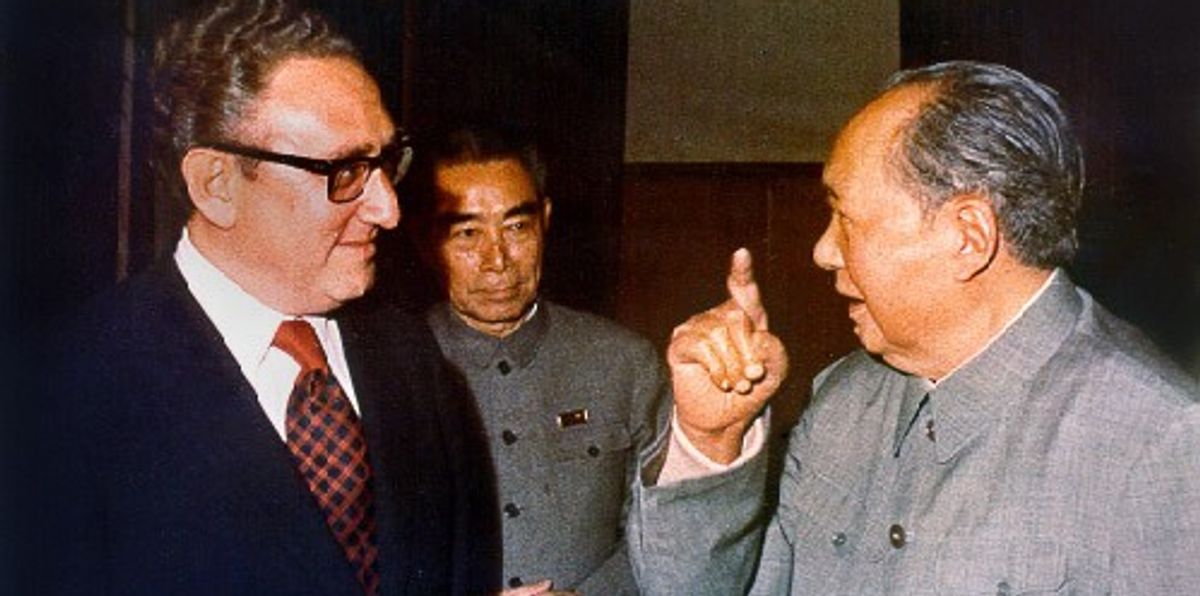

Kissinger’s answer to this problem, conceived in partnership with President Nixon, was a masterwork of diplomatic realism. Seeing an opportunity to exploit tensions between Moscow and Beijing, he orchestrated a surprise opening to Maoist China that reshaped the international order, counterbalancing Soviet power and complicating the Kremlin’s strategic challenge. In parallel, the United States pursued détente with Moscow, producing a landmark set of trade, arms control, human rights, and confidence-building arrangements that helped to constrain the arms race and make the Cold War more manageable and predictable.

By comparison to 1968, the scale of the problems we face today seems more daunting. The Cold War architecture of arms control and security arrangements is in tatters. Our middle class is more distrustful and disaffected, our international reputation more damaged, and our ability to manage the challenges of a peer Chinese rival more limited. A statesman with Kissinger’s strategic acumen and diplomatic skill is very much needed.

Tom Blanton, Director, National Security Archive, George Washington University

The declassified legacy of Henry Kissinger undermines the triumphant narrative he labored so hard to build, even for his successes. The opening to China, for example, turns out to be Mao’s idea with Nixon’s receptiveness, initially dissed by Kissinger. His shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East did reduce violence but it took Anwar Sadat and then Jimmy Carter to make the peace that Kissinger failed to accomplish. The 1973 Vietnam settlement was actually available in 1969, but Kissinger mistakenly believed he could do better by going through Moscow or Beijing.

Meanwhile, Kissinger’s callousness about the human cost runs through all the documents. Millions of Bangladeshis murdered by Pakistan’s genocide while Kissinger stifled dissent in the State Department. A million Vietnamese and 20,000 Americans who died for Kissinger’s “decent interval.” Some 30,000 Argentines disappeared by the junta with Kissinger’s green light. Thousands of Chileans killed by Pinochet while Kissinger joked about human rights. Untold numbers of Cambodians dead under Kissinger’s secret bombing.

Adding insult to all these injuries, Kissinger cashed in over the past 45 years through sustained influence peddling and self-promotion, paying no price for repeated bad judgments like opposing the Reagan-Gorbachev arms cuts, and supporting the 2003 Iraq invasion. A dark legacy indeed.

Michael Desch, Professor of International Relations at the University of Notre Dame

Almost all of the obituaries for Henry Kissinger characterize him as the quintessential realist, harkening back to a bygone era of European great power politics in which statesmen played the 19th century version of the board game Risk otherwise known as the balance of power.

Kissinger seemed straight out of central casting for this role with his deep, sonorous voice and perpetual Mittel-Europa accent. All that was missing was a monocle and a Pickelhaube.

But in reality, Kissinger was at best an occasional realist.

His best scholarly book — “A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-22” — came out in 1957 and was more of a work of history than an articulation of a larger realpolitik theory of global politics in which power is used, and more importantly not used, to advance a country’s national interest.

And while his (and Richard Nixon’s) opening to the People’s Republic of China in 1972 remains a masterstroke of balance of power politics in action, at the drop of an egg-roll dividing the heretofore seemingly monolithic Communist Bloc, he was more often an inconstant realist.

At times Kissinger embraced a crude might-makes-right approach (think of the Athenians bullying of the Melians in Book V of Thucydides) epitomized by the escalation to deescalate the war in Vietnam by invading Cambodia and the meddling in the fractious politics of Third World countries like Chile, seemingly to no other end than that’s what great powers do.

More recently, he’s worked to remain the indispensable statesman through an embarrassingly obsequious pattern of making himself indispensable to nearly every subsequent president, whether or not they were really interested in sitting at the knee of the master realpolitiker. His hedged endorsement of George W. Bush’s disastrous Iraq war is exhibit A on this score.

Kissinger kept himself in the limelight for much of his career but not as a consistent voice of realism in foreign policy.

Anton Fedyashin, associate professor of history, American University

In his long and distinguished career, Henry Kissinger made many decisions that history may judge harshly, but oversimplifying and exaggerating complex geopolitical issues was not one of them. With their instinctive aversion to the trap of conceptual binarism, Kissinger and Nixon applied their flexible realism to China and the USSR in 1972. Abandoning the assumption that all communists were evil forced Beijing and Moscow to outbid each other for U.S. favors. Treating the USSR as a post-revolutionary state that put national interests above ideology, Nixon and Kissinger decided to bring the Soviets into the American-managed world order while letting them keep their hegemony in Eastern Europe.

In Kissinger’s realist version of containment, statesmanship was judged by the management of ambiguities, not absolutes. As Kissinger put it in an interview with The Economist earlier this year, “The genius of the Westphalian system and the reason it spread across the world was that its provisions were procedural, not substantive.” Kissinger’s realist wisdom would serve American leaders well as they navigate the rough waters of transitioning to a multipolar world order. The era of great power balancing is back, and non-binarist realism can help Washington manage hegemonic decline rather than catalyzing it.

Ambassador Chas Freeman, visiting scholar at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs

Kissinger embodied a global and strategic view and because it was global, it often offended specialists in regional affairs. Because it was strategic, he often made tactical sacrifices for strategic gain. And the tactical sacrifices that he made were often rather ugly at the regional or local level. The classic example of that is the refusal to intervene in the war in Bangladesh.

Obviously, he had nothing but contempt for ideological foreign policy. This has led ideologues, of which we have an abundance, to see him as an enemy, and you're seeing this now with some of the coverage after his passing.

Kissinger's achievement of detente at a crucial point in the Cold War will be remembered for its brilliance, as will his significant scholarship. His statecraft and scholarship were inseparable. He was a very good negotiator and probably had more experience negotiating great power relations than any secretary of state since early in the Republic. He was moderately successful in the short term. He was not successful in the long term because his interlocutors correctly perceived that he was manipulative. If one wishes to keep relationships open to future transactions, one must not cheat on current transactions. But this problem is not uncommon. It's very typical in American politics. For example, Jim Baker was famously uninterested in nurturing relationships. He was interested in immediate results in his dealings with foreign governments. He left a lot of anger and dissatisfaction in his wake. Kissinger less so, but the same for different reasons, reflecting his personality, his character, and the character of the president he served.

John Allen Gay, Executive Director, John Quincy Adams Society

Kissinger's legacy in the Third World commands the most attention and criticism. He has been made the face of the tremendous toll the Cold War took on the wretched of the earth. Yet his work on great power relations deserves more regard. The opening to China he engineered with President Richard Nixon was a masterstroke to exploit division in the Communist world. Granted, the Sino-Soviet split had happened long before, and the opening was more a Nixon idea, but Kissinger set the table. And Kissinger was also a central figure in détente with the Soviet Union.

Both policies were deeply unpopular with the forerunners to the neoconservative movement, but reflected the Continental realist mindset that Kissinger, along with thinkers like Hans J. Morgenthau, brought into the American foreign policy discourse. The opening to China and détente were, in fact, linked. As Kissinger pointed out, the opening to China challenged the Soviet Union to prevent the opening from growing; contrary to the advice of Sovietologists, this did not prompt new Soviet aggression, but made the Soviets more pliable. As Kissinger wrote in his 1994 book "Diplomacy" — “To the extent both China and the Soviet Union calculated that they either needed American goodwill or feared an American move toward its adversary, both had an incentive to improve their relations with Washington. […] America’s bargaining position would be strongest when America was closer to bot communist giants than either was to the other.”

And so it was. Today’s practitioners of great-power politics would do well to borrow more from this happier part of Kissinger’s legacy. They have instead helped drive China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea together, and have no answer to this emerging alignment beyond lectures and sanctions. The19th century European statesmen Kissinger admired would have seen the failure of such a policy.

David Hendrickson, author, "Republic in Peril: American Empire and the Liberal Tradition"

The great oddity of Nixon and Kissinger’s record in foreign policy is that they gave up as unprofitable and dangerous the pursuit of ideological antagonism with the Great Powers (the Soviet Union and China), but then pursued the Cold War crusade with a vengeance against small powers. Kissinger’s diplomatic career reminds me of the charge that Hauterive (a favorite of Napoleon’s) brought against the confusions of the ancien regime, that it applied “the terms sound policy, system of equilibrium, maintenance or restoration of the balance of power . . . to what, in fact was only an abuse of power, or the exercise of arbitrary will.”

Parts of Kissinger’s record, like the bombing of Cambodia, are indefensible, but there are good parts too: had Henry the K been in charge of our Russia policy over the last decade, we could have avoided the conflagration in Ukraine. He was sounder on China and Taiwan than 90 percent of the howling commentariat. He was, in addition, a serious scholar who wrote some good books about the construction of world order (A World Restored, Diplomacy). Young people should take his thought seriously, not consign him to the ninth circle.

Robert Hunter, former U.S. Ambassador to NATO

Like all outstanding teachers, Henry Kissinger was also a showman — and he could be fun. He used his accent and self-deprecating humor as weapons for his policies and getting them taken seriously. Journalists might at times scorn what he was doing and how he did it, but they were still charmed and tended so often to give him the benefit of the doubt — as well as the credit, even when not deserved. Everyone recalls his roles in promoting détente with the Soviet Union and, even more, the opening to China, with Richard Nixon following in his wake. In fact, both policies sprang from Nixon’s mind. But when the dust settled, Kissinger was the Last Man Standing.

“Henry,” we could call him who never worked for him (!), made intelligent and literate speeches on foreign policy that everyone could understand, bringing it into the limelight. A man of great ego, he still recruited and inspired talented acolytes at the State Department and White House — matched only by Brent Scowcroft and Zbig Brzezinski. He had other policy positives in the Middle East (“shuttle diplomacy”) but major negatives in Chile, in prolonging the Vietnam War, and bombing Cambodia.

Take him altogether, a true Man of History.

Anatol Lieven, Director of the Eurasia Program at the Quincy Institute

The problem about any just assessment of Henry Kissinger is that the good and bad parts of his record are organically linked. His Realism led him to an awareness of the vital interests of other countries, a willingness to compromise, and a prudence in the exercise of U.S. power that all too many American policymakers have altogether lacked and that the United States today desperately needs. This Realist acceptance of the world as it is however also contributed to a cynical disregard for basic moral norms — notably in Cambodia and Bangladesh — that have forever tarnished his and America’s name.

When in office, reconciliation with China and the pursuit of Middle East peace took real moral courage on Kissinger’s part, given the forces arrayed against these policies in the United States. But in his last decades, though he initially criticized NATO expansion and called for the preservation of relations with Russia and China, he never did so with the intellectual and moral force of a George Kennan.

Perhaps in the end the best comment on Kissinger comes from an epithet by his fellow German Jewish thinker on international affairs Hans Morgenthau: “It is a dangerous thing to be a Machiavelli. It is a disastrous thing to be a Machiavelli without Virtu” — an Italian term embracing courage, moral steadfastness and basic principle.

Stephen Miles, President, Win Without War

Nearly as many words have been spilled marking the end of Henry Kissinger’s life as the lives he’s responsible for ending, but let me add a few more. It would be easy to simply say that the devastating impact of Kissinger on U.S. foreign policy was clearly and wholly negative. As Spencer Ackerman noted in his essential obituary, few Americans, if any, have ever been as responsible for the death of so many of their fellow human beings.

But Kissinger’s true impact was not just in being a war criminal but in setting a new standard for doing so with impunity. Earlier this year, he was feted with a party for his 100th birthday attended not just by crusty old Cold Warriors remembering ‘the good ole days,’ but also by a veritable who’s who of today’s elite from billionaire CEOs and cabinet members to fashion megastars and NFL team owners. Sure, he may have been responsible for a coup here or a genocide there, but shouldn’t we all just look past that and recognize his influence, power, and intellect? Does it really matter what he used those talents for?

And in the end, that’s the benefit of Kissinger’s horrific life and decidedly not-untimely death. By never making amends for the harm he did and never being held accountable for the horrors he caused, he made clear just how truly broken and flawed U.S. foreign policy is. Perhaps now that he has finally left the stage, we can begin to change that.

Tim Shorrock, Washington-based journalist

Kissinger nearly destroyed three Asian countries by causing the deaths of thousands in U.S. bombing raids, covertly intervened to subvert democracy in Chile, and encouraged an Indonesian dictator to invade newly independent East Timor and inflict a genocide upon its people. These were criminal acts that should have made him a pariah. Instead, he is lauded as a visionary by our ruling elite. And it was mostly accomplished through lies and deceit, in the name of corporate profit.

I'll never forget in 1972 watching Kissinger declare "peace is at hand" in Vietnam. After years of protesting this immoral war, I truly thought that Vietnam's suffering, and my own countrymen's, was finally over; they had won and we had lost. But my hope was shattered that Christmas, when Kissinger and Nixon ordered B-52s to carpet-bomb Hanoi in an arrogant act of defiance and malice. Afterwards, a shaky peace agreement was signed that could have sparked an honorable U.S. withdrawal. But it took 3 more years of bloodshed before the United States was forced out.

Kissinger broke my trust in America as a just nation and overseas sparked a deep hatred of U.S. foreign policy. Few statesmen have caused such harm.

Monica Duffy Toft, Professor of International Politics and Director, Center for Strategic Studies, Fletcher School, Tufts University

I have a pair of midcentury teak chairs once belonging to the late eminent scholar Samuel P. Huntington in my office. Sam was a colleague and friend of Henry Kissinger’s, and a mentor to me. Sam and I sat in these chairs discussing world politics and the everyday challenges of running a scholarly institute. When a new set of chairs arrived, Sam insisted I take the old ones, but not before emphasizing their significance — reminders of the hours he and Kissinger spent in deep debate and casual banter. These chairs have history.

Henry Kissinger was, and shall remain, a controversial figure. His gifts were two. First, across decades of U.S. foreign policy challenges, he remained consistent in his conception of power, and how U.S. power should be used to enhance the security of the United States. Second, he was gifted at assembling, mentoring, and deploying cross-cutting networks of influential people. Like many of my colleagues who study international politics, there are policies — his support of Salvador Allende’s ouster in Chile, for example — I find odious. I am also uncomfortable with Kissinger’s elitism: his preferred policies favored those with wealth and political power at the expense of those without.

But what I admire about Kissinger’s U.S. foreign policy legacy and, by extension, international politics, was his profound grasp of the importance of historical context: a thing as important to sound U.S foreign policy today as it is rare; and of which I am pleasantly reminded every time I sit in one of Sam’s chairs.

Stephen Walt, Quincy Institute board member, professor of international affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School

Henry Kissinger was the most prominent U.S. statesman of his era, and that era lasted a very long time. His main achievements were not trivial: a long-overdue opening to China, some high-wire "shuttle diplomacy" after the 1973 October War, and several useful arms control treaties during the period of détente. But he was also guilty of some monumental misjudgments, including prolonging the Vietnam War to no good purpose and expanding it into Cambodia at a frightful human cost. His diplomatic acrobatics in the Middle East were impressive, but they were only necessary because he had missed the signs that Egypt was readying for war in 1973 in order to break a diplomatic deadlock that he had helped orchestrate. His indifference to human rights and civilian suffering sacrificed thousands of lives and made a mockery of U.S. pretensions to moral superiority.

Kissinger owed his enduring influence not to a superior track record as a pundit or sage but to his own energy, unquenchable ambition, unparalleled networking skills, and the elite’s reluctance to hold its members accountable. After all, this is a man who downplayed the risks of China’s rise (while earning fat consulting fees there), backed the disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003, opposed the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran, and dismissed warnings that open-ended NATO enlargement would make Europe less rather than more secure. Kissinger also perfected the art of transmuting government service into a lucrative consulting career, setting a troubling precedent for others. Debates about his legacy will no doubt continue, but one suspects that the reverence that his acolytes exhibit today will gradually fade now that he is no longer here to sustain it.

No comments:

Post a Comment