Syrian Civil War

Introduction: The Historical Inevitability of The Syrian Civil War and the Rise of Militant Islam

The ongoing Syrian Civil War (2011-present) is significant to the region and world for a plethora of reasons. More specifically of the many past and current events of this unstable crisis, the Syrian Civil War arose from and later began the counter-revolution against the same turbulent social and political instability of most Arab states within the Middle East that started in 2011 otherwise known as the Arab Spring, and from this counter-revolution emerged the Islamic State and other militant groups to oppose the Syrian regime’s reassertion of control. However very few politicians, pundits and policymakers look at the history of the Syrian state and its role in the region to realize that a dangerous interregional and localized conflict was likely going to occur at some point in time, and due to the overbearing actions taken by the Assad dynasty’s brutal and systemic authoritarian Presidential Dictatorship it was almost guaranteed that the Islamic State or something like it would rise to power in the region.

How Syria Came to Be

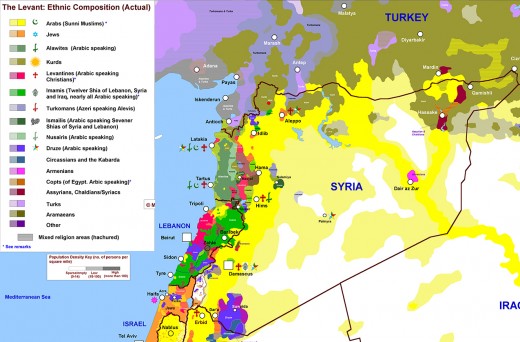

Syria from its very conception as state was originally created without consideration for the historical make-up of the diverse regional population incorporated within it (Cleveland, 187). Due to this lack of legitimacy, the rulers of these nations were from the start forced to initiate a balancing act between the wishes of their population and with powerful Western forces externally influencing events in the region, such as with the role of the Syrian National Bloc, an organization of influential families in Syria originating from the Ottoman era, in serving as an intermediary between the Syrian public and the French rulers in the 1920s (Cleveland 189-190, 213). When the Mandate system put in place by the victories British and French in World War I to indirectly control Iraq and Syria decayed and Western control over their puppet states gradually collapsed, Syria was finally able to wrestle its independence from France in 1946 after victory in elections for pro-independence factions in the newly re-established parliament (Cleveland 195). Despite the elections the oppressive, divisive colonial political institutions that were created upon these state’s birth were not abolished and instead were restructured to cement the control of the new local ruling elite to take the place of the former French overlords (Cleveland 197, 200). The current state political ideology known as Ba’athism, was initially embraced by the new dictators who called themselves presidents such as Syria’s Hafez al-Assad and Iraq’s Saddam Hussein who had overthrown the civilian led governments there shortly after their formation (Cleveland 205-208). Ba’athism’s founder Michel Aflaq (1910-1989) originally created the ideology to emphasize Arab unity, liberation, democracy, nationalism and socialism, but when the ideology was officially adopted by the Syrian and Iraqi states it was used selectively as a political tool to accomplish regional and domestic goals and its principles were distorted and stretched to accomplish these goals, such as Hafez al-Assad’s use of its ideological concepts of equality and democracy to create a rubber stamp parliament and ensure his minority Shi’a offshoot Alawite faction attained many prominent positions of power within the government (Cleveland 303, 308, 383-384). The overall policy of Syria during this era represented a devotion to pragmatism, calculation, and realism that ended up using the Ba’athist ideology as a political tool for indoctrination and whose principles were not needed to be followed strictly and were not based on Islamic morals which is exemplified by Assad’s educational reforms that dramatically increased educational opportunities of the population but were subject to Ba’athist ideological indoctrination, and also with the secular reforms in both nations that gave historically unprecedented rights to women despite domestic conservative Islamic backlash from the population (Cleveland 314-315). Despite the fact that the regime in Syria and (as well as the one in Iraq) were founded as artificial, non-representative, and colonial states that later adopted secular, nationalist, and socialist policies, there was always a varying degree of grassroots Islamic movements within these nations that were continually oppressed (Cleveland 217, 226). Many examples of this oppression and subversion took place throughout Syria’s modern history, for example al-Assad’s brutal destruction of the Islamic popular revolt centered on the Syrian city of Hama in 1982 that resulted in the death of at least 10,000 people (Cleveland 412-414). Despite these politically convenient gestures made to the domestic populations of Syria, Assad never fully committed himself to their own principles of their Ba’athist ideology, let alone that of political Islam, and even though the domestic populations of Syria holds significant Islamic influences, the very structures of the political institutions in these nations were created with the intention of controlling and influencing their populations and the departure of the French colonial masters did not result in local aspirations of the citizens of these nations being realized and instead resulted in the perpetuation of this cycle of repression being carried out by the new domestic political elite in place of the former colonial rulers (Cleveland 312-319). This reality explains why the ideals prevalent after the independence of the Arab states in the region such as pan-Arabism, secularism, socialism, and nationalism may have created some positive benefits to the domestic population through social and economic reforms, but these concepts failed to achieve greater political liberation for the Arabs and other ethnicities of the region and were instead used pragmatically and conveniently by the Ba’athist regimes as a political tool to perpetuate their political dominance and ensure the stability of what essentially amounted to a pair of mafia-states in Syria and Iraq, which effectively suppressed the simmering discontent within their domestic populations and left the greater political questions of the region to be unresolved (Cleveland 314-320, 412).

Current Issues and Possible Future Outcomes

The long debated greater political questions include examples such as what is Syria and Iraq exactly? How can Syria’s ethnic and religious minorities as well as the Sunni Arab majority gain more equality and representation in the Shia Alawite ruled government? And what role should Islam play in Syria’s secular government? The answer to these questions are not apparent now, but following the conclusion of the Civil War we will have bigger understanding of how to tackle these questions in the new paradigm that emerges. Questions such as was an Arab Spring type uprising inevitable in Syria, and did Hafez al-Assad’s successor son current President Bashar al-Assad’s oppressive policies contribute to the rise of ISIS, are much newer and can be argued much more conclusively. The artificially drawn borders in Iraq and Syria that do not in any way reflect any useful demographic division between the people living there resulted in many communities being separated and distinct ethnic and religious groups clumped together. The French built this state on this unstable foundation, and added to the instability to give political power to the small Shia Alawite group and politically powerful and wealthy Sunni Arabs, creating a government enforced inequality, divisiveness, and oppression that carried on through the local political elites once the French left (Cleveland 189-190). The result is this mafia state keeps its population at a slight simmer an occasionally has to issue a bloody crackdown to brutally stamp out any opposition such in Hama in 1982 (Cleveland 412-414). However, in essentially all Arab states in the region, there exists a large amount young adults with or without college degrees and searching for work in stagnant economies leading to poverty, dissatisfaction, and discontent which is commonly believed led to the Arab Spring protests. Due to all of these underlying repressed issues and since the Syrian Regime already had past problems with revolt before the Arab Spring, once the initial wave of demands for bread, jobs, and dignity began, it was only a matter of time that the equivalent protests that emerged would evolve towards advocating reform and elections. Assad could never accept true reforms because it would result in his Ba’athist minority elite group losing complete control over the state, and after seeing how quickly the protests in Egypt and Tunisia escalated and later removed their dictators there was no way Assad could propose meager skeleton reforms and listen to the growing crowds of protestors to try to wait it out like the abolished dictators did. So he chose to answer with complete and total force and pushed the peaceful protestors out and began instigating an armed conflict with the opponents of the regime who eventually took up arms to defend themselves. Brutalizing your own people is not an acceptable action to international powers and Assad knew that he would not be able to simply suppress the civil uprising for long. So he labeled all people opposing his regime as terrorists of the same quality the West was fighting all around the world. The narrative sounded purely propagandist initially, but as Syria’s civilian population fled and militants from all around the world flooded in, and soon enough Muslim extremist groups such as Islamic State and al-Nusra Front have solidified and also began attacking the original opposition group the Free Syrian Army. After the Islamic State seized most of western Iraq and began trading oil and resources secretly with Assad at the expense of the moderate opposition, Assad managed to elicited the help of Russia in the form of a thinly veiled military intervention justified under the politically loaded goal of “fighting terrorism” to turn the tide of the war from near defeat to likely victory. Regardless if Assad completely wins his Civil War, he has already won enough international political legitimacy to claim he is fighting a civil war against terrorists. Since the international community and particular the United States now feels that the threat from Islamic militants in the region is a bigger threat then to spend previously considered resources on a humanitarian or military intervention to stop Assad’s brutal crackdown, Assad’s narrative has become a self-fulfilling prophecy of his own contribution. Because the international threat of Islamic militants subsiding any time soon is very unlikely, for now there are even debates ongoing between the involved parties about whether Assad should be included as an alliance of convenience in a future military coalition, giving him even more undeserved international legitimacy to quietly continue his brutal systemic crackdown of his people indefinitely.

Works Cited

Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East. 6th ed. Boulder: Westview, 2016. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment